Yesterday, the 1st of July, 2019, was the day the Singaporean government took yet another step in its ongoing battle with smoking.

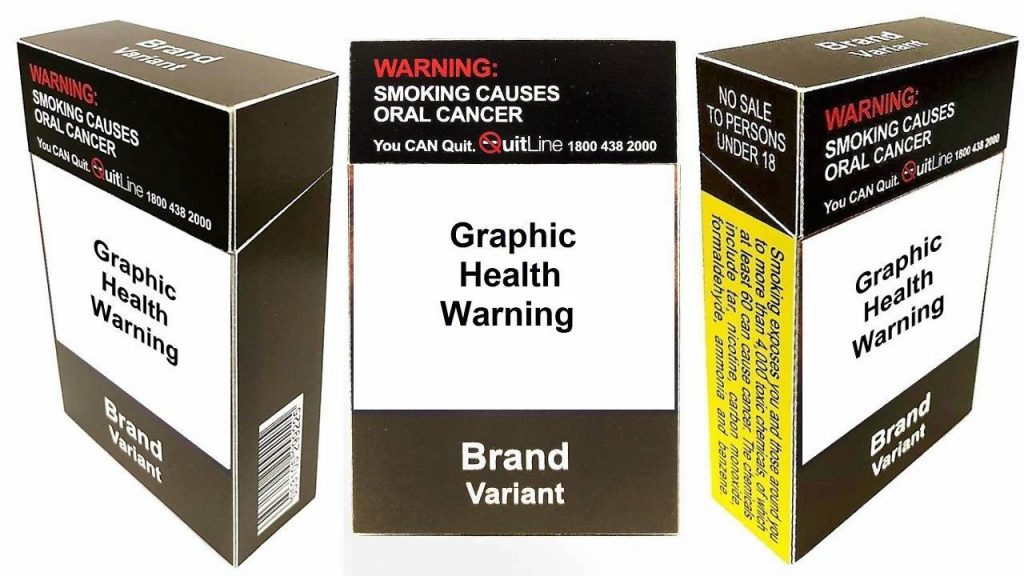

In a statement released by the Ministry of Health (MOH), the government mandated that from 1st July next year, all tobacco products sold must have standardised packaging and enlarged graphic health warnings, making good on its promise to implement the change—collectively known as the SP measure—from October last year.

This means all tobacco products (cigarettes, cigarillos, cigars, beedies, “ang hoon” and other roll-your-own tobacco products) will be sold in a standardised colour sans logos, brand images, and promotional information. Brand and product names will still be allowed, but again, only in a standard colour and font style. Additionally, the size of the graphic health warnings on cigarette packets will be increased from 50 to 75%.

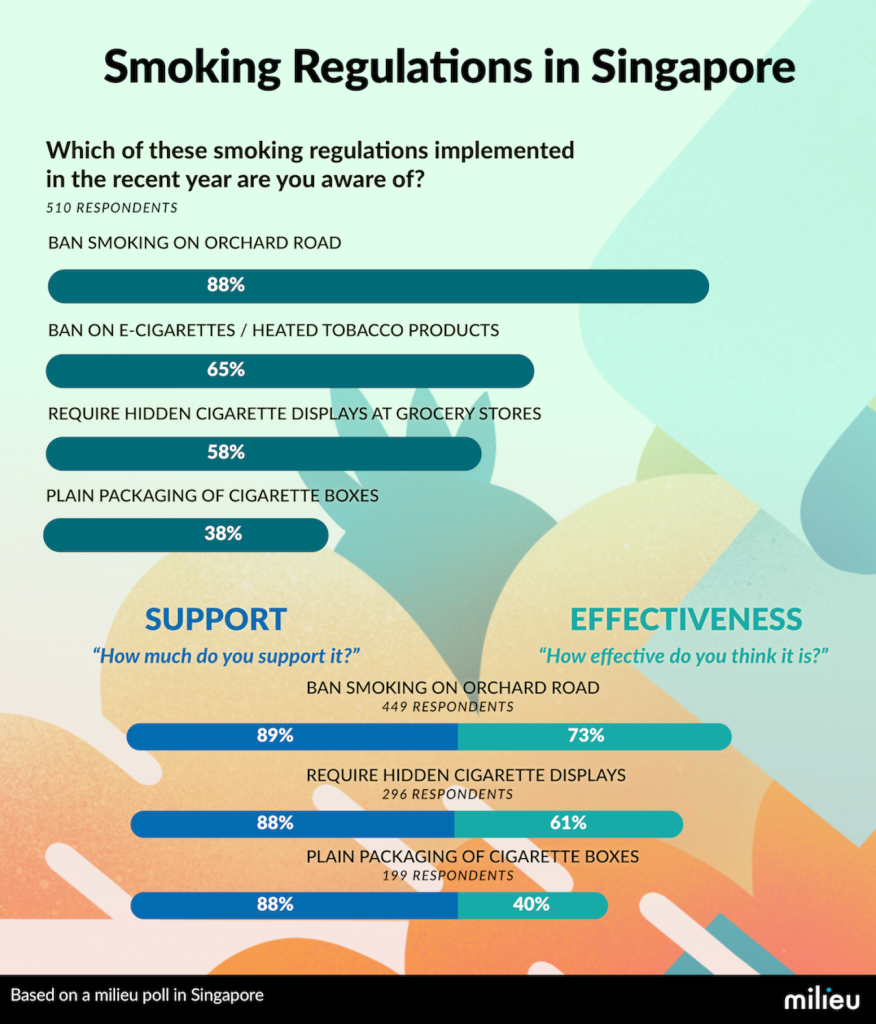

MOH’s latest regulations join other measures that have already been put in place to curb smoking such as raising the minimum legal age for smoking (from 18 to 19 on the 1st of January 2019 and raised progressively each year until 2021), a ban on point-of-sale display of tobacco products in August 2017, and of course, banning smoking along Orchard Road (save for designated smoking areas).

Mandatory standardised packaging for all nicotine products is supposed to deter smoking by removing positive associations of brands with the consumption of tobacco.

In theory, this sounds fantastic in both preventing potential smokers from picking up smoking and getting smokers to quit. Too bad it won’t work.

This figure is one that’s consistent across the board when it comes to other means of methods of smoking cessation—88% support hidden cigarette displays and 89% support the smoking ban along Orchard Road.

And yet, while the number of those who believe these other methods will be effective is relatively high (73% in the case of banning smoking along Orchard road and 61% for hidden cigarette displays), the converse is true for the implementation of standardised packaging.

From the data, it’s clear Singaporeans want a smoke-free nation so why do we think standardised packaging won’t work?

Quite simply, it’s because we all know and believe that standardised packaging does nothing to stymie the appeal of a cigarette.

As a smoker myself, trust me when I say that whenever I reach for my pack, its colour and design are the least of my concerns; I can’t be arsed if cigarettes came in a cardboard box adorned with images of Mickey Mouse or Mr Bean. In the words of every relationship guru: it’s what’s on the inside that counts.

And while we’re on the subject of design, don’t get me wrong, health warnings are indeed useful. But only to a certain point. When you’re confronted with images of a dead baby or a bloody, cancerous organ every time you want a puff, people are bound to think twice. Which is great. But for those who’re simply too addicted to quit smoking or who’ve smoked for a long time, we’ve gradually learnt to ignore these fearmongering tactics. We light up anyway.

“We already know that smoking is bad and we’re well aware of all the health risks but when you’re addicted to something, you just block it out. The whole world could be telling you no but your mind just wants to satisfy that craving or urge. They say quitting is all in the mindset but it’s really not that easy.”

Elsewhere, Gary’s sentiment is echoed by 28-year-old Agnes Tan, a self-confessed heavy smoker for the past 9 years.

“Making it more difficult for smokers to light up [by restricting the number of places they can] definitely works because we don’t wanna get fined by the NEA. But when you need a smoke, you will find a way no matter what—whether it’s walking another 500 metres or buying cigarettes in standardised packaging.”

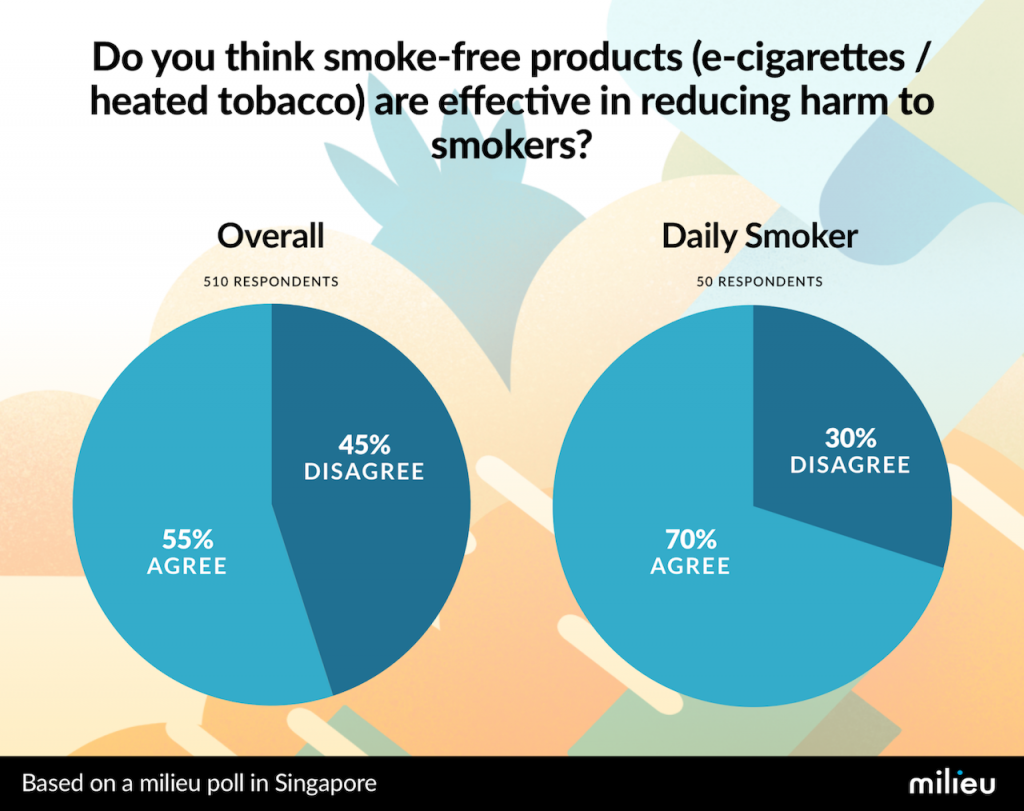

It’s painfully obvious that the implementation of standardised packaging on cigarette packets to reduce the overall harm of smoking in Singapore will never work. This then naturally leads me to wonder: why are things like e-cigarettes or heat-not-burn tobacco products not legal?

This view is one that is shared by many Singaporeans. According to the Milieu survey results, a higher percentage (55%) of people believe that alternative smoking methods will be more effective in reducing harm than simply selling tobacco products in standardised packaging(40%).

So why does the government choose to focus on changing how a cigarette packet looks instead of what chemicals enter the people’s lungs? Why are we taking a measure that’s not only failed to work, but has actually been shown to increase smoking prevalence instead of one that will?

Will we remain insistent on flogging a dead horse? And if so, for how long?

Tackling the problem of smoking is already complicated enough. We need to decide where our priorities lie and figure out what is truly important: simply repackaging the issue so it appears we’re doing something, or actually trying to help.

If anything, we need to remember that whenever a smoker uses less harmful methods of smoking or eventually quits, society on the whole benefits. Their loved ones don’t get affected by second-hand smoke; non-smokers have cleaner air.

Win-win-win.