Despite the title, this article is not about Monica Baey, Nicholas Lim or NUS. It’s about how Singaporeans are talking about the case, and how this discourse reveals deeper issues that might be worth thinking about.

What is Justice?

The term “justice” is not in many Singaporeans’ vocabularies, but the majority of discourse and disagreements have revolved around this concept.

In the Monica Baey case, justice (or lack of it) can be analysed at three levels—

1. At the case level: was the outcome unjust in the case of Monica vs Nicholas?

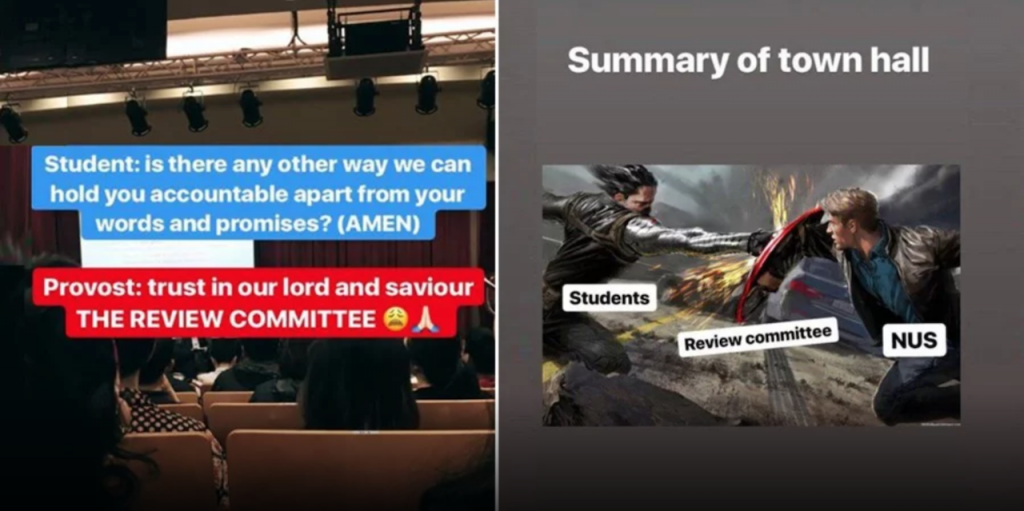

2. At the institutional level: has NUS and/or SPF been handling cases of sexual misconduct unjustly?

3. At the systemic level: as a society, have we been blinded to the injustice of such cases due to our cultural biases?

While I believe all three questions are legitimate (and also controversial), part of the complexity of this discussion is the inability of many Singaporeans to differentiate the three levels (as well as whether NUS or the police ought to be the rightful target of critique).

But more fundamentally, all three questions hinge on the concept of what is “just” or “unjust”. This is something many people believe to be straightforward and intuitive, but I will attempt to show you that it’s not quite so simple.

We can’t avoid the fact that we now live in an age of moral outrage fuelled by social media.

Second observation: people disagree on the purpose of a “just punishment”. After all, punishment serves a combination of up to four different purposes: retribution, deterrence, incapacitation and restoration.

Retribution is about making sure a guilty person suffers in a way commensurate with the seriousness of his offense. Deterrence is about discouraging other people from committing similar crimes, preventing future victims. Incapacitation is for dangerous criminals who need to be removed from society such that they can no longer harm innocents. Restoration is about helping a perpetrator reintegrate back into society to reduce the likelihood of repeat offences.

In Nicholas’ case, people disagree on what the primary purpose of the punishment ought to be (or the correct proportion of a mix of purposes). One party values retribution and deterrence more (and feel that Nicholas’ punishment was too light); the other party values restoration more, thus the punishment was appropriate, and a harsher punishment would compromise its restorative aim.

I’m not a lawyer or a theorist on jurisprudence, but it seems clear to me that our concept of what is “just” depends on a few things: our personal capacity to empathise, who we choose to dehumanise, and the value we place on various conflicting things that we also consider good.

The first two are related. If we empathise with Monica more, we’re more likely to dehumanise Nicholas. If we empathise more with Nicholas, we’re more likely to dehumanise Monica. Our degree of moral outrage, and towards whom it is directed, is directly correlated to our empathy levels.

One important point to note is that since this is a criminal offence, there is indeed a victim and a perpetrator. One can argue that the victim demands more sympathy and the perpetrator deserves to be dehumanised. I won’t refute this argument directly, but this position potentially leaves no space for restorative justice, and I also think it stems from an overly simplistic understanding of human nature: only “bad people” commit crimes, and thus they do not deserve to be treated as humans.

I hope most adults realise that the world is much more grey than this, and that even the best of us are capable of causing grievous hurt and pain under the “right” circumstances.

But the issue I most wish to discuss is about different value judgements on competing good things. To make sense of this, let’s discuss a somewhat parallel case: the discourse around marital rape.

Those who advocate for criminalising marital rape value something good—the right for people who have been legitimately raped by their spouses to seek criminal justice. On the other hand, their opponents also desire something good—for spouses to not be falsely accused of rape.

The question then becomes about which “good” you value more. Not surprisingly, our intuitions differ on this, partly because our intuitions are likely uninformed by facts.

For most of us, we don’t really know the likelihood that someone will be falsely accused of rape, and we don’t really know the number of people who suffer in silence due to marital rape. We can use only our own intuitions to guess, and our intuitions tend to side with which scenario we personally fear more.

In the case of Monica vs Nicholas, what are the two competing “goods” that we differ intuitively upon?

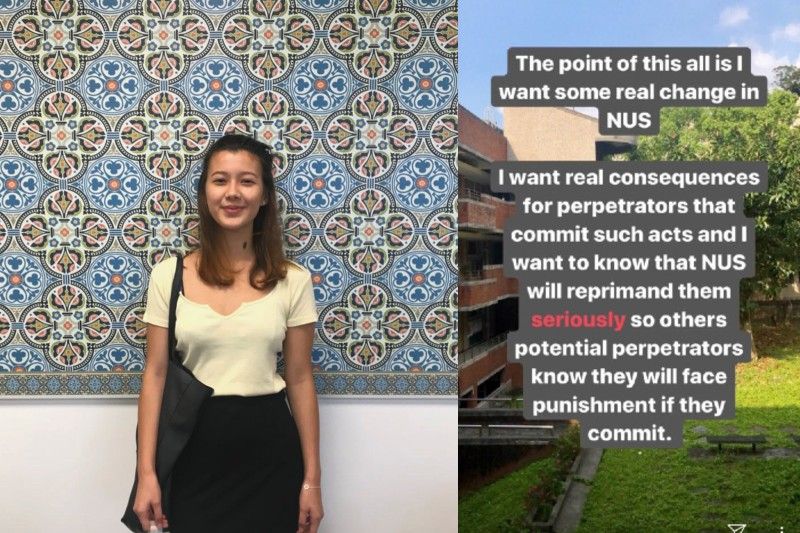

For the pro-Monica camp, it is certainly that NUS can be a safe campus for ladies, and perhaps some kind of desire for society to better address the hidden fears of women which have been unaddressed a for a long time.

But what about the “pro-Nicholas” camp? This brings us to the next point.

The bulk of the pro-Nicholas camp isn’t defending Nicholas for his offence, but are upset about the means Monica has used to address her concerns.

In particular, her use of social media to mobilise “mob justice”, which arguably has been successful in getting NUS to reform their disciplinary policies. The “weaponising” of social media isn’t new in Singapore of course; Amy Cheong losing her job at NTUC and Avijit Das Patnaik losing his job at DBS are two such examples.

Most recently, the last minute banning of the Watain concert can also be interpreted as a successful example of mob justice. In the backdrop of Singaporeans who appear to be increasingly thin-skinned, making police reports over anything they find offensive, there is a legitimate fear that certain kinds of advocacy via social media might actually perpetuate injustice instead of justice (arguably, this has already happened in the doxxing of Nicholas and his family members).

While I think this is a legitimate fear, I also feel the ship has sailed on this.

We can’t avoid the fact that we now live in an age of moral outrage fuelled by social media. [If you are tempted to think that POFMA will save us from this, I believe you are quite deeply mistaken]. And depending on how you feel about unaddressed injustices in Singapore, you might even feel that on the whole there is a net increase in justice (as is the case of Monica and NUS and/or SPF), and therefore this “age of outrage” isn’t such a bad thing.

To me, the real downside isn’t new injustices being introduced (although that is definitely a bad thing), but that Singapore society is moving towards the kind of polarisation as seen in America, and rational discourse may soon become impossible (if not already).

I believe the discussion around the Monica Baey case is further evidence of this.

I see the polarisation of Singapore society as inevitable, although more optimistic souls exist and they believe greater media literacy as the solution. Why I am more pessimistic has to do with what I said above about our individual differences in empathy and values, and our lack of ability to engage meaningfully with someone from a different worldview.

These won’t go away even if we all attend a lecture series in media literacy. Perhaps the only sustainable solution lies in education—training students from young in empathy, discourses on justice, and the ability to disagree well. But as of now, that has no place in our current exam-driven education system.

I don’t have a good solution, and perhaps a “solution” is the wrong term, since not everybody sees this as a “problem”. I just think we all need to brace ourselves for a new kind of Brave New Singapore, and try to live our lives as wisely as possible.