I am glad that people are finally recognizing the importance of our essential workers, but even before the pandemic, we have never been able to function without cleaners, security guards, or construction workers. Covid-19 may have spotlighted the necessity of our hitherto invisible labour, but they were always essential to begin with.

So if these jobs have been, are, and will be so essential, then why are they so lowly paid?

The simple answer is that although the jobs themselves are essential, the people performing them aren’t.

To put it crudely, even though society has a clear need for these essential jobs, these jobs can be filled by nearly anyone (if they are willing). The people working in these jobs are easily replaced. I’m not talking about doctors or nurses, professions that obviously require many years of training and require strict credentials to even enter. I’m talking about jobs like cleaners and garbage collectors, which are what economists would call “low-skilled” jobs.

These jobs have low barriers to entry, and thus, a large supply of potential workers. As any student of Econ 101 might tell you, what determines wages is a matter of demand and supply. The logic of open borders and global capitalism means that Singapore will always have a ready pool of cheap labour to import to fill those roles. The large labour surplus thus depresses wages for those working in these industries, for both locals and foreigners alike.

Their replaceability does not mean that these essential workers don’t have power. They do—especially in countries where there are strong labour laws and trade unions. In countries like France and the United States, essential workers like garbage collectors have organised strikes in order to demand better working rights and higher wages. Their absence is sorely felt, for people soon realise they can’t function with their garbage left outside their houses.

Chapter 67 of the CLPTA explicitly states that the act is meant for the “prevention of strikes and lock-outs in essential services.” This means that the government is well aware that certain jobs are essential—in fact, it takes pains to list out exactly what these are: apart from public and air transport services, it also includes newspaper services, sewerage and waste water treatment services, electricity and gas services, and so forth.

The fact that essential workers are unable to strike without the requisite two weeks’ notice should be a clear sign of their lack of labour power. (To be fair, these rules about strike notice for essential workers are not unique to Singapore. What is unique is that these workers are foreigners, and are thus easily deportable—MOM can revoke their work passes at any time.)

This is why I think that debating about which jobs are essential misses the point. What we should be asking ourselves is why these essential workers have not been able to make their “essential-ness” felt—a question that would prompt us to examine our labour laws, the strength of independent trade unions, and the overall resonance of labour rights in Singapore.

The disparity between how essential these jobs are, and how lowly those who perform them are paid, should also ask us to consider if a strictly capitalist view of economic value should be applied in our assessment of “essential” jobs. We might instead adopt the view that the economic value these jobs bring is higher than what the market pays, and/or that the government should intervene by raising minimum wages in these sectors in order to promote a more equal society.

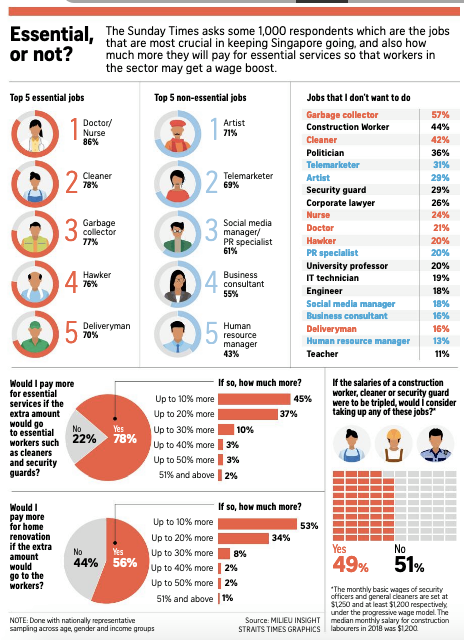

In fact, Milieu already had a working definition of what “essential” jobs are—one provided to them by ST*. In the very same survey that asks people to rank which jobs they consider essential, they essentially spoonfeed the survey respondent with this definition: “By ‘essential workers’ we mean someone who is engaged in work deemed necessary to meet basic needs of human survival and well-being, such as food, health, safety and cleaning.”

I’m not sure why we are surprised that people picked “hawker” and “garbage collector” as essential work after ST already kindly told us, through Milieu, what ‘essential work’ meant (*hint*: “food, health, safety, and cleaning”).

The question is, why wasn’t this essential context provided for ST’s readers?

Potentially flawed survey design aside, what is more interesting is how people responded to the survey. Many responded with shock, grief, and outrage. Why is it so shocking to us that some jobs, while highly-paid, are deemed unessential, whereas those which are essential are lowly-paid? Perhaps it is because we are used to thinking about the value of work primarily in how highly they are paid, and how much social prestige they get.

This view speaks to how our ideas about the value of work is coloured by a capitalist notion that the free market decides what the economic value of work is, and that the economic value they bring should correspond to how essential they are.

What Covid-19 has done is that it has upended this notion, and put things in perspective about what society’s baseline functioning looks like.

In fact, anarchist anthropologist David Graeber might go a step further, and point out that most jobs today are neither essential nor important. In his compelling monograph entitled “Bullshit Jobs”, he unpacks several categories of useless jobs such as “Goons”, “Flunkies”, and “Box-tickers”. The sole purpose of “goons”, for example, is to pad the self-importance of their superiors: think doormen, or accessory receptionists.

For all the butthurt artists, business consultants, and HR managers, ask yourself, does the framing of your job as “non-essential” actually change the way you think of your own job? No, because the realities are, whether you admit it or not, these occupations still carry some form of economic benefit, social status and cultural prestige (at least for artists), and certainly have far more recognition than most of the top five “essential” jobs.

To be honest, I couldn’t care less about whether some random ST-commissioned survey suggests whether my work is essential or not, as long as it pays me a living wage to do something I don’t actively dislike. And if we were honest with ourselves, we would admit that most of our jobs aren’t “essential” anyway.

I certainly don’t think RICE writers are.

P.S. The only winner of this useless “essential jobs” debate is ST and the “unessential” advertising industry—think of all the eyeballs they managed to monetise for clicks.

*This article was amended at 5:37 PM on 16th June 2020 to qualify that the definition Milieu used for ‘essential work’ was provided to them by the Straits Times.