For all of Singapore’s supposedly progressive, world-class education, the Ministry of Education (MOE) would barely score a C6 in arguably its most crucial subject: sexuality education.

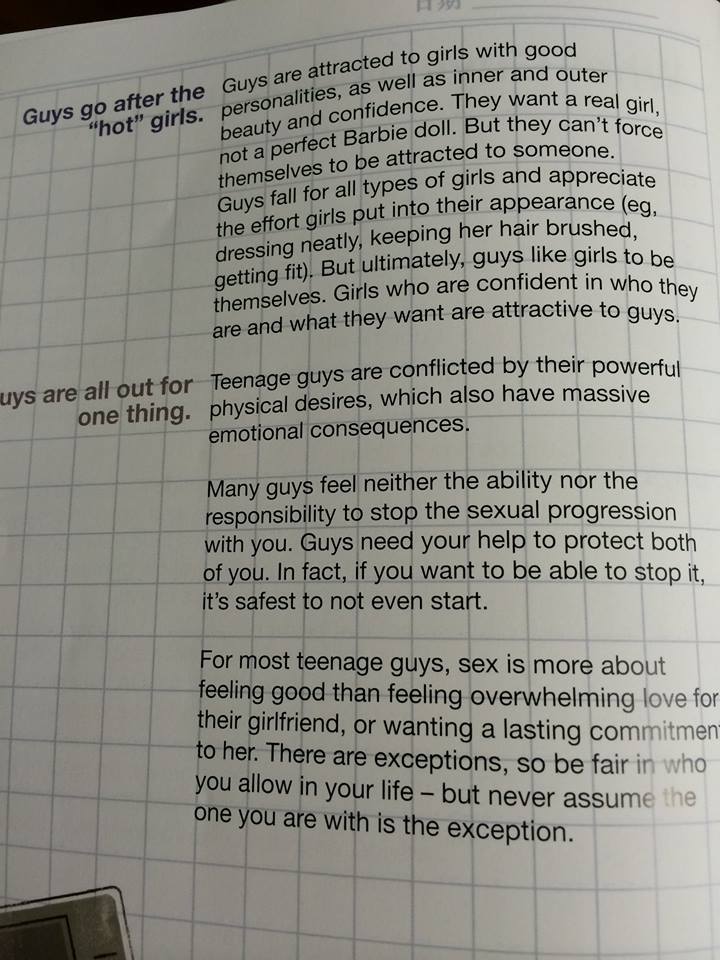

3 years ago, junior college student Agatha Tan made headlines when she wrote a letter to her principal after attending a sex ed workshop conducted by family-first organisation, Focus on the Family (FotF). She also took photos of the workshop’s material, explaining how FotF’s conservative values implicitly condoned sexism and rape culture.

The thought-provoking letter, posted publicly on her Facebook, received more than 2,000 shares.

But stories like hers were nothing new. Growing up, we’ve all heard whispers of similar experiences: male and female students separated and taught different things, the perpetuation of gender stereotypes, and so on.

At the end of that same year, MOE halted all external vendor services for sex ed workshops. Even though family-first organisations are not explicitly associated with any religion, the move by MOE emphasised the secularity of its sex ed curriculum.

Despite this claim, the key messages and goals of sex ed include “practising abstinence before marriage” and “developing mainstream values and attitudes about sexuality”. Sex ed is also “premised on the family as the basic unit of society”.

The language used is neutral and palatable, so these messages appear reasonable. But they continue to echo conservative and, arguably, religious beliefs.

The fact is that encouraging ‘abstinence only’ behaviour over education on contraception overlaps with the values of MOE’s former sex ed vendor, FotF. The organisation, which has received grant money from its American Christian affiliate, also believes that “the family unit is the basic building block of a thriving nation”.

Coincidentally, the government’s policy on protection and welfare of families under the Ministry of Social and Family Development states that “the family is the basic building block of society”.

Is secularity in Singapore’s sex ed curriculum then just a carefully constructed illusion?

Promoting abstinence is just an attempt to avoid uncomfortable conversations about sex.

How many teenagers are able to understand this, especially when schools, which are responsible for shaping their values, tell them otherwise?

After speaking with a few secondary 2 students, my concerns feel more valid: their sex ed teachers indirectly suggest that premarital sex is “a bad thing”. One of them shares that her teacher would talk about friends whose relationships fell apart after having premarital sex, leaving her class to draw their own conclusions.

In fact, abstinence-based sex ed has the potential to be more bad than good.

“What happens is that youth who do have sex are ill-equipped to do so safely and respectfully. The information they gather on their own may also be inaccurate, which adds to misconceptions and lack of preparedness for safe and consensual sex,” says Agatha, now 20 and a student at Yale-NUS.

The reality is that teenagers who are going to have premarital sex will do it anyway. For those who don’t, knowing this stuff equips them to eventually engage in healthy sexual relationships as young adults.

Hence, brushing up on one’s knowledge about all aspects of sex can only prove useful. Many students, for instance, don’t know that sexually transmitted infections can spread through oral sex. Then there are those who, lacking the right knowledge, engage in unsafe anal sex because — like oral sex or other forms of sexual stimulation — it is supposedly ‘not sex’.

The 33-year old runs Please, an “educated pleasure shop” in Brooklyn, New York, committed to promoting conversations around sex that are open, truthful and non-judgemental.

“Having to adhere to a ‘rule’ without understanding why only makes it more tempting not to. I feel that promoting abstinence is just an attempt to avoid uncomfortable conversations about sex,” she says.

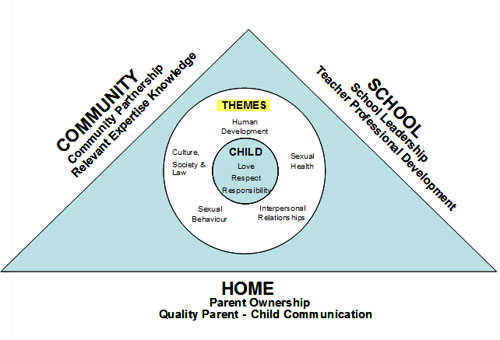

Back home, local gender equality advocacy group, AWARE, believes in “creating a society where everyone is empowered to safely navigate their sexuality”. Their sex ed classes are held in international schools. And unlike MOE’s approach to sex ed, AWARE’s classes accept the reality that the student population will be sexually active in their future – an important point to note for critics who argue that contraception education encourages us to ‘sleep around’.

Executive director Corinna Lim shares, “Acknowledging this fact means that our curriculum will provide accurate and non-judgmental information about abstinence as a personal choice. We also teach the usage of condoms and contraception where one chooses to have sex.”

Like Agatha and Sid, she feels that using fear tactics to promote abstinence and limit sexual expression is counterproductive.

“Demonising sex outside of marriage creates a culture of shame and fear, discouraging young people from seeking information and help. This is especially harmful if they have faced sexual abuse, unplanned pregnancies or sexually transmitted infections.”

And then there’s the common knowledge that as teenagers, we are all the more attracted to forbidden fruit.

Under the sex ed curriculum, talk of homosexuality, if any, is accompanied by “the current legal provisions concerning homosexual acts in Singapore”. Sex ed teachers are also advised not to use schools to advocate for “controversial issues”.

Sid believes that all this implicitly suggests it is wrong and unacceptable not to be heterosexual.

“For straight youths, it encourages disregard and can lead to deep resentment towards anything that is different. Eventually, this manifests in subtle ways through interactions with each other,” she adds.

Even though it is useful knowing how to navigate both romantic and sexual encounters with the opposite sex, Agatha also feels that sex ed should explore alternatives to “compulsory heterosexuality”. For youth who remain unsure of their sexuality, seeing themselves represented in official sex ed material reduces the feeling that they’re “abnormal and alone”.

Shame is the biggest barrier to talking about sex.

Instead, it’s how our youth now have to deal with the resulting culture of shame and taboo surrounding sex that comes from reinforcing abstinence and conservative values.

In the days following Agatha’s viral post, what disappointed her more than FotF’s workshop was that her teachers actively skirted around talking about the ‘problematic’ material. They only wanted to know how she was coping.

“I found it impossible to approach teachers with any questions or concerns about sex,” she says.

“Back in school, there were also rumours of students who were expelled or transferred because they’d been caught making out or having sex on campus. Sure, school is not the most appropriate place, but these rumours only reinforced that any kind of sexual activity was secret or taboo.”

Despite growing up in a completely different environment, Sid echoes Agatha’s sentiments. As a teenager, Sid could only speak about sex with her friends.

However, their conversations didn’t revolve around the act itself. Mostly, they worried about being judged and what their parents might think or say.

“Shame is the biggest barrier to talking about sex. Whether the purpose is to educate, share or vent, we feel a certain discomfort and shyness when the topic comes up. We also use shameful words to describe people who are open about sex, such as ‘slut’ or ‘dirty-minded’. This vocabulary perpetuates judgement and discourages open conversations.”

As a result, Sid practises what she preaches in her own career: a forthcoming culture of transparency and open mindedness.

“Like sex, my store should be shame-free. I even call myself a slut to own the term. We need to remove the negative power that such words have on our psyche so we can move forward. If any sexual expression outside of the bedroom is considered sleazy and perverted, what hope is there for better sex ed?” she questions.

Still, it’s naive to expect MOE (and society) to drastically change overnight, even if our students deserve better than sanitised language. Perhaps, the first step forward would be to acknowledge the overly simplistic nature of the current sex ed curriculum.

Besides, if students will eventually realise that life isn’t always so black-and-white, what safer place to prepare them for this than within the four walls of a classroom?

By talking to our youth about sex, we also empower them to respect their bodies.

That is reassuring, but normalising all talk of sex further would also benefit our youth. To do this, Sid proposes that sex ed be made a school subject, like science or home economics.

“The less we make a big deal out of sex, the easier it will be to teach. By talking to our youth about sex, we also empower them to respect their bodies, own their pleasure and be accountable for their actions.”

Likewise, Agatha believes that students should be allowed to collaborate on what they would like to learn in sex ed.

She says, “Youth aren’t completely ignorant of sexual matters, so defining their own learning experience enables them to gain information personally relevant to their own sexualities and interests.”

The truth is, if MOE really wants to nurture and broaden young minds, they have to embrace independent learning and thinking in all aspects, including sexuality.

It may take awhile to dispel the unfounded fear that our youth are fully impressionable. But if they truly lack the ability to differentiate between education on safe sex and encouragement to have sex, then our great education system faces a deeper failure than merely inadequate sex ed.