I know, because I used to do freelancing work a few years back. It coincided with the time when many of my friends were getting married, and I absolutely hated going to wedding dinners because of the inevitable “What do you do?” question at a table of strangers.

“I am a freelancer,” I would reply. Inevitably, their faces would contort, feigning interest while trying to take control of the condescension and pity that were their immediate, instinctive, responses.

Such sentiments towards freelancers are the norm in Singapore, where freelancing is seen as an euphemism for “unemployed” or a stop-gap measure for someone “unable to land themselves a real job”. Freelancing, the argument goes, is a stagnant job, not a career with built-in progression and skills training.

Nothing could be further from the truth. If anything, freelancing—and, by extension, the gig economy freelancers operate in—could be a model of how the labour market operates in the future.

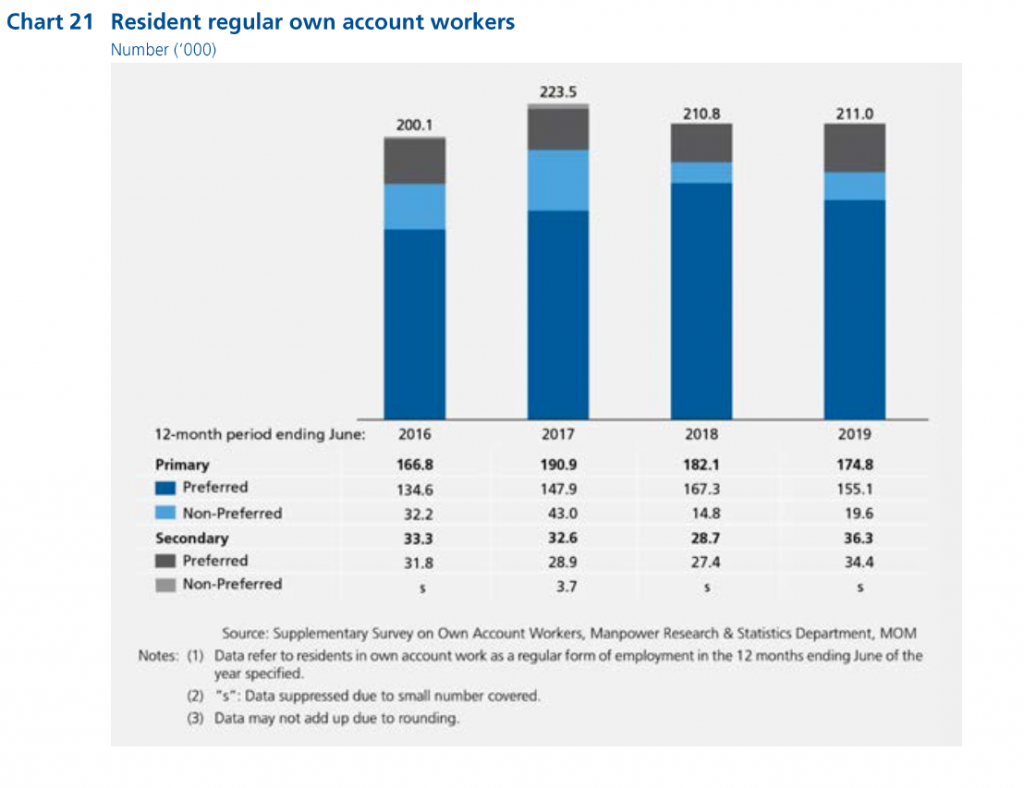

In Singapore, the number of people engaging in freelance work has been increasing across the years, according to the Ministry of Manpower’s (MOM) annual Labour Force Reports. In 2016, there were about 200,000 freelancers; last year, the number rose to 211,000. Though it dipped slightly from the high of 223,500 in 2017, overall, the number still displays an upward trend.

More fresh graduates are also heading straight into freelance work, instead of more conventional jobs. Newspaper reports on Joint Graduate Employment Surveys through the years reveal that 2% of fresh graduates were engaging in freelance work in 2017, compared to 1.7% in 2016.

As the years go by, these numbers are only going to get bigger. A research paper on the gig economy, written by two professors of occupational health, concludes that “contingent arrangements are expanding beyond traditional occupations in both private and public sectors … gig platforms are replacing at least some traditional employment.”

Removing such impediments brings about greater efficiency and lower costs, most of the time. And there is nothing more attractive to a free market economy than these two qualities. Thus, economists and academics recognise that the gig economy is not going anywhere.

For instance, a professor of public policy opines that we, and our government, need to adapt to the gig economy, not avoid it. Likewise, a Harvard Business Review op-ed argues that “universities should be preparing students for the gig economy”.

Indeed, universities here are already responding to the seismic changes in our labour force. At SUSS, for example, courses and workshops on the gig economy are already integrated into the curriculum. The university also organises the SUSS Ministerial Forum, where students get the chance to talk to ministers—last year, it was Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong himself—on issues like future-proofing their careers.

As Professor Calvin Chan, Director of the Office of Graduate Studies at SUSS points out, we must “embrace these opportunities and commit to lifelong learning, so that we can confidently … deal with changes in the global economy.”

I don’t know enough about the economy to elaborate on these factors; my expertise lies in talking about myself. So I will do just that and try to explain why freelancing can be so attractive to an individual—and, in the process, hopefully dispel some myths about this much-maligned course of work.

For me—and many others, I suspect—the main attraction of freelancing is flexibility.

The rigid temporal and physical confines of a traditional desk-bound job just don’t work for everyone. While freelancing, I was free to work in Starbucks, in a park, or even on my bed (and you know what a big advocate of working from home I am, especially in our current health situation). As someone deathly allergic to mornings and sunlight, I could also work when I felt most productive, usually from 6 PM to 2 AM, instead of trying to keep myself awake from 9 AM with pots of scalding tea, just to keep up with morning people.

Flexibility in choosing the type of work was another reason why I chose to do freelance work for a time. Of course, I did not manage to get hired for all the projects for which I pitched or applied, nor did I have the luxury of saying “no” to a job. Nonetheless, I consciously marketed myself as a researcher and creative writer, so I was lucky to find projects relevant to my skillset and interests, which made work more than tolerable.

Which brings me to my next point: in my opinion, freelance work is hardly a dead-end job that cannot be your career. On the contrary, you become your entire company. You get exposed to opportunities and are forced to develop skillsets you never thought you needed.

When I was freelancing, I had to invoice companies, then chase them for payment (these companies will remain unnamed but cursed forever), manage my working hours, reach out to publications, maintain relationships, market myself, curate my portfolio … in other words, I was Karen from HR, Rob from accounting, Trevor from marketing, etc. etc.

Indeed, “the gig economy has also paved the way for individuals and small companies to become more entrepreneurial,” a professor of finance says in a newspaper article. Thus, even as universities are preparing their students to adapt to the gig economy, they must not neglect entrepreneurship skills. For example, SUSS, as aforementioned, has integrated classes on the gig economy into its curriculum. But it also runs mentorships and bootcamps to foster entrepreneurs, who are, after all, the original freelance workers.

I’m being shameless, but that’s exactly how I felt when I was doing freelance work: a sexy Jeff-Bezos-type entrepreneur launching his multi-million dollar product and/or spaceship all on his own, with only a slight difference in scale.

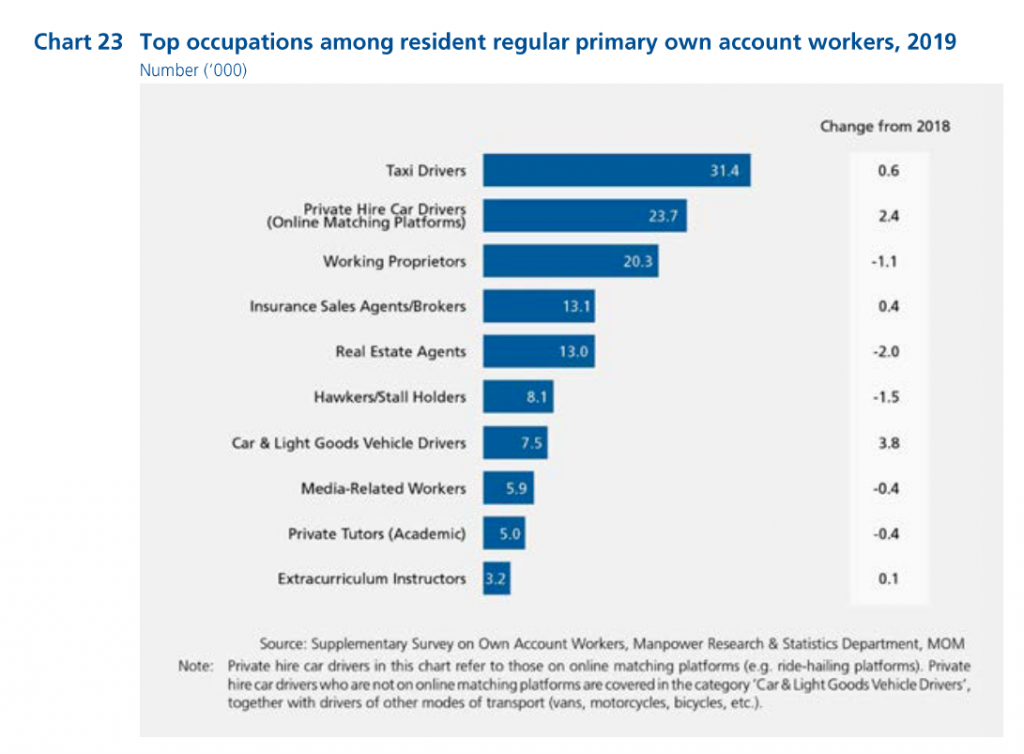

Yet the fact remains that most of the freelancers and gig workers in Singapore are engaged in trades such as transport or food delivery, fields in which most criticisms regarding career stagnation and exploitation are levelled. (According to MOM’s 2019 report, there were 23,000 private-hire car drivers, compared to 5,900 media-related workers.)

Associate Professor Walter Theseira from SUSS also describes freelance jobs like driving as having “little hierarchical structure and are fairly simple … [which] mean that no employer hiring for a permanent career position will take most gig-economy experiences seriously as evidence of fitness for a job that requires significant technical and management skills, or which requires substantial discipline.”

Freelance work, in this light, deepens the hole in which underemployed people—individuals whose qualifications or experience outstrip their current job scope—already find themselves in. Freelance work is a trap that will not set free the people who turn to it because they cannot secure full-time employment at a firm.

I don’t know if the gig economy is a symptom or cause for scenarios like these. But intervention in these situations is undeniably necessary.

However, we should not forget that some people consciously choose to be a private-hire driver, for instance. Perhaps it’s because they want more flexibility in working hours to spend with their children, or they are sick of the corporate rat race. As the wife of a Grab driver writes:

…

Sometimes having a particular job is a circumstantial choice. Sometimes it’s a personal choice. Why do we need to question it? Why do we need to feel like we’re mightier than others when we work in a cushy job and an air-conditioned office, but still have to report to someone of higher authority?

As long as one works hard, sets targets and achieves his goal, any job can be a rewarding one.

And that’s what the gig economy is for, and why it has been expanding annually: it gives you the opportunity to choose what you want to do, and, more importantly, choose what you want to prioritise in your life.

As long as one works hard, sets targets and achieves his goal, any job can be a rewarding one.

It’s not just full-time freelancers (an irony in terms, but you get what I mean). Students are earning a side income doing writing jobs. Accountants who work on weekends as wedding photographers. Retirees who are bored of staying at home are now terrorising, sorry, transporting people around Singapore—proving true the assertion that the retirement age is becoming a meaningless number today, as Dr Nicholas Sim, Senior Lecturer at SUSS’s School of Business points out.

A group of economists from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) agree. In a paper on the gig economy, they write: “[the gig economy has] potentially positive effects on aggregate productivity and employment … Overall, most gig workers are satisfied with their job and working for gig economy platforms appears to reflect mainly voluntary choices rather than the lack of other options.”

Our policies, then, need to catch up with the rate of adoption of freelance work. There are some initiatives already put in place, like the Central Provident Fund’s (CPF) contribute-as-you-earn (CAYE) scheme, in which companies will contribute to a freelancer’s Medisave account. Currently, it only applies to freelancers working with the government, but may eventually be extended to the private sector.

Because of the uncertain economic conditions caused by Covid-19, the government is also introducing a SkillsFuture scheme that pays all freelancers who attend select courses S$7.50 an hour.

Aside from these government-led schemes, ground-up movements are also intent on improving the working conditions for freelancers. For instance, in 2018, the Law Society of Singapore published a free legal handbook, Advocate for the Arts, to educate freelancers on their legal rights.

But there are some other areas in which being a freelancer does truly suck. The lack of paid leave and medical coverage are the most pressing issues. Again, I have no economics or public policy knowledge, so I have no suggestions as to how to solve them except: “please sir, can you give freelancers more money and medical insurance”.

Does that diminish the shine of freelancing? Surely. But what we need, I think, is more protections for freelancers, not regulation of the gig economy—which is here to stay.

What are your favourite (and not-so-favourite) parts of working in the gig economy? Commiserate with us at community@ricemedia.co.