Unless otherwise stated, all images in this piece were supplied by residents of the Cochrane dormitory, who cannot be named to protect their identities.

Nearly two months have passed since early February, when the first cases affecting migrant workers were reported. (The critically-ill Bangladeshi worker from the Leo dorm remains in the ICU.) Since then, Covid-19 clusters have mushroomed in workers’ dormitories. The largest, at the S11 Dormitory @ Punggol, went from four cases to 62 in under a week. The Westlite Toh Guan dormitory now has 28.

There are now clusters in at least four other dorms and three worksites. As of Monday morning, over 100 migrant workers have tested positive for Covid-19 in the last week.

As local cases increased, so did fears about asymptomatic transmission. Slowing—and preparing—for community spread quickly became a priority.

And yet, as late as end March, when the entertainment venue closures were announced and many businesses were weeks into their continuity plans, it was still radio silence from the government about the ticking time-bomb that was workers’ dormitories. Now the situation has exploded, and everyone is scrambling.

We might all be in this together, but the brutal truth is that Covid-19 does not affect us all equally.

Social distancing, as a viral social media post put it, is a privilege. It does not apply to the slums of New Delhi or the refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar. In 1800s Singapore, poor Chinese coolies died from tuberculosis by the hundreds because the congested, airless shophouses they lived in made transmission inevitable.

Workers’ dorms are a far cry from decrepit shophouses, but they are still death-traps when it comes to outbreaks like Covid-19.

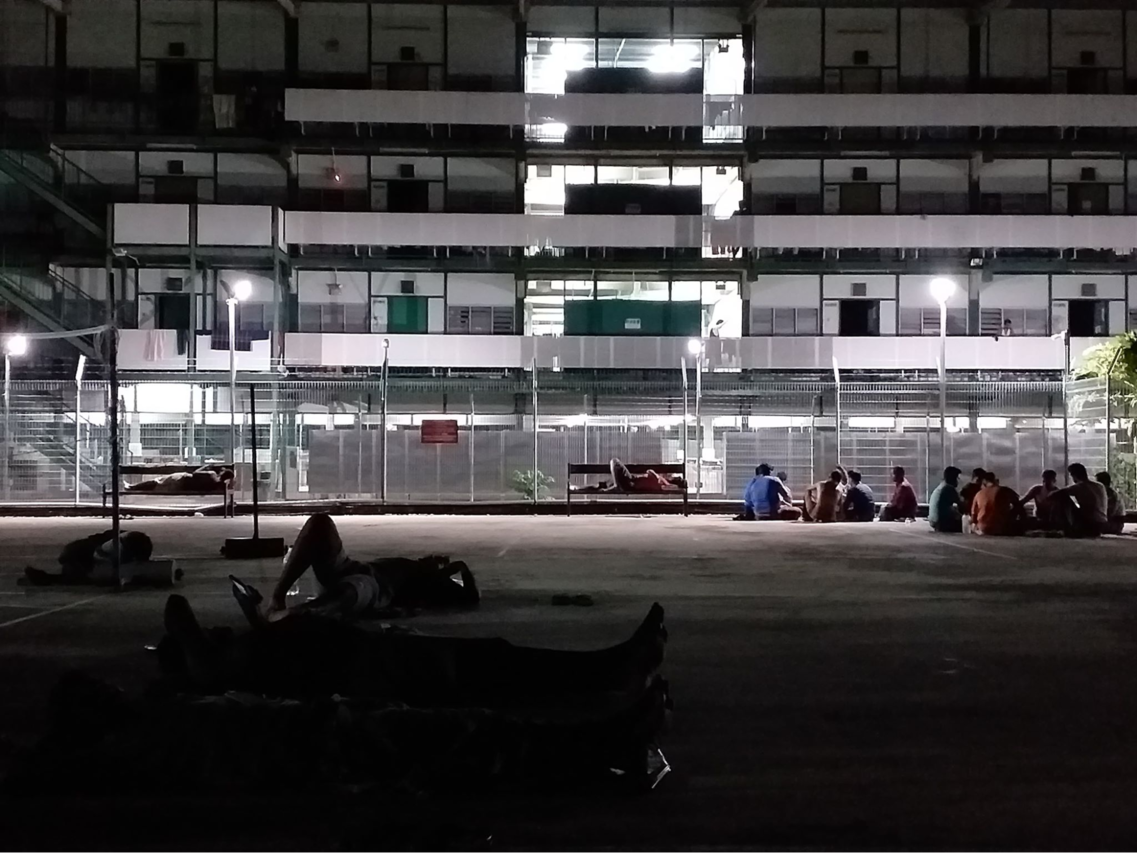

The very setup of dorms makes safe distancing impossible. A single dorm can house over 10,000 men, who are squeezed 15 to a room on bunk beds, use shared bathrooms, and cook shoulder-to-shoulder by the hundreds in mass kitchens. The minimum floor area per occupant is 4.5m², which means up to 20 workers can be housed in a space the size of a 4-room HDB flat.

Talking about distancing in ‘communal areas’ implies the existence of separate, private spaces. This distinction is useless in dorms, which are entirely made up of communal areas.

It is farcical to stick Xs on half the dining room tables while ignoring the glaring issue of the bedrooms. Many men find them so unbearably stuffy that they would rather sleep out in the open, which they do.

Despite this, as recently as April 2nd, MOM’s advice to dormitory operators was that workers should “stay in their rooms and minimise physical interactions”. No advice was given on how to achieve this—probably because it can’t be done.

Migrant worker NGOs have campaigned about overcrowding in dormitories for years. A 2014 medical sciences paper noted previous outbreaks of typhus and pneumonia, possibly due to dorms’ “high density” and “occasionally less than satisfactory sanitary living conditions”.

After the first cases in February, activists and NGOs sounded the alarm. Cai Yinzhou, the founder of Geylang Adventures, published a note with comprehensive recommendations, including decreasing the number of residents per room and earmarking dorms for suspected cases to be isolated.

On February 10th, MOM issued an advisory recommending the suspension of mass activities and staggering the use of common facilities ‘where possible’. The extent to which this was followed is unclear, and varied with dorms.

Weeks later, MOM’s approach was still focused on ‘education’ and ‘personal responsibility’:

“We ask for the cooperation of workers to take necessary precautions and exercise individual responsibility. MOM also urges … dormitory operators to educate their workers and residents on the advisory to remain at home or in dormitories on their rest days.”

(MOM Press Release, March 25th)

No mention of further distancing measures in dorms appears to have been made till April 1st, after the clusters at S11 and Westlite Toh Guan emerged, and more than a week after MOH announced large-scale distancing measures on March 24th.

Even so, gaps existed in the measures which had been implemented. According to one resident from the Cochrane I dormitory in Woodlands, who cannot be named to protect his identity, temperature-taking was not consistently done because queues were getting too long.

And for all the advice to ‘take precautions’, most dorm residents had not been given masks, hand sanitiser, or extra personal care products. The dorms themselves were still notoriously filthy, with garbage piling up, insect infestations, and broken amenities left unfixed for weeks. The situation had not changed from when I wrote about this in February.

In this context, the emphasis on ‘personal responsibility’ is really little more than ‘thoughts and prayers’. Translation: ‘good luck, you’re on your own’.

A lot can happen in two months. Since February, there have been two (soon to be three) Budgets, two mask distribution exercises, and progressively tighter movement controls. If we want to get things done, we can.

So why the lag? Given the potential for catastrophe, why did the government squander its precious lead time?

Misinformation and poor awareness is a legitimate concern, but a separate issue from dormitory overcrowding, which is beyond either residents’ or dormitory operators’ ability to solve. Only top-down instruction can achieve large-scale coordination of the kind necessary in ordinary times, let alone in a health crisis.

This was a strikingly obvious problem which needed time, attention, and resources to solve. The government could, and should, have acted much sooner. It did so with Singaporeans who needed help getting home from overseas exchanges and job postings. But right under our noses, migrant workers were once again left high and dry.

It would be laughable, and impossible, for the government to claim ignorance of how bad things could get. The more plausible assumption is that they simply did not care enough.

The bitter irony is that Singapore’s legendary preparedness has always been a point of pride. If making contingency plans was an Olympic sport, we would be World No.1. Time after time, our leaders have extolled that our vigilance, foresight, and talent for problem-spotting have saved our asses.

What if food imports dry up? Don’t worry, there’s a plan A, B, C, and D for that. Need to tap into the reserves? We can do that, we’ve been saving very prudently for years. What if Malaysia stops selling us water one day? No worries, we’ve been anticipating that since 1965!

The foot-dragging over workers’ dorms has exposed the hollowness of this self-praise. It is sickening hypocrisy to laud workers for their ‘contributions’ and lament how the UK and Switzerland ‘abandon[ed] any measure’ to contain the virus, when the dormitory issue was left unaddressed in plain sight. Our celebrated, ‘gold standard’ response had a citizenship blind spot.

On Sunday evening, MOM announced that it would finally be taking action to mitigate the spread at dorms. The most sweeping of these was the lockdown at S11 and Westlite Toh Guan, now gazetted as ‘isolation areas’.

Good, you might say: this prevents the spread of cases from these dorms to the wider community. But it also makes sitting ducks of nearly 20,000 men now trapped in a space where transmission is already ongoing. More ominously, it sounds little different from the UK government’s much-derided decision to let ‘herd immunity’ take care of things.

Measures were also announced at other dormitories, including moving ‘essential services’ workers into other spaces, reducing intermingling between floors, and housing sick residents (even if not positive) in isolated sick bays.

All of this is commendable, but comes regrettably late. Over the weekend, activists and NGOs received accounts that sick workers, or workers on LOA/SHN, were still being housed in the same rooms as their counterparts.

Moreover, no timeline has been given for when the new measures would be rolled out, nor any commitment made to giving all workers reusable masks and/or sanitisers.

If we want to prevent further spread in the dorms, decisive steps need to be taken right now. One, ramp up cleaning frequency. Ensure residents are kept well informed, in languages they can understand, and given adequate supplies free of charge.

Workers should also be reassured, in line with the government’s announcements, that they will not be penalised in any way for seeing a doctor and/or missing work. Operators who do not comply should be held accountable in the strictest possible terms.

Two, alternative housing arrangements should be looked into without delay. It is an ambitious task, but a necessary one, given how safe distancing is essentially futile. TWC2, the NGO, has come up with some suggestions; it is a total failure of imagination, not to mention a huge risk, to say there is simply ‘not enough space’. At the very least, all workers who are sick, on LOA, or SHN, should be promptly isolated in separate facilities.

Say all you want about ‘unity’ or ‘resilience’ or ‘solidarity’: a society is only as good as the protections we offer our most vulnerable. Now is not the time for empty words. We need to stop only caring about our migrant workers when they become corpses.

Migrant worker NGOs and community groups, like HOME, TWC2, itsrainingraincoats, Citizen Adventures, Project Chulia Street, and One Bag One Book, are all in need of assistance. If you are willing and able to, please send support their way.

In the meantime, send us your thoughts on this story at community@ricemedia.co.