This was the conclusion of the 2018 report released by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). If you haven’t already heard, it outlines the terrifying consequences of failing to act swiftly to mitigate climate change.

If we don’t fix things by 2030, we will almost certainly be on a one-way course to annihilation. Moreover, the report was based on the ‘best case’ scenario. Feedback loops, like methane released by melting ice caps, or burning forests that act like stores of coal, will both accelerate the crisis and amplify its impact.

As an island city-state with no natural resources of its own, nearly entirely reliant on imports for our electricity, water, and food, Singapore has more to lose than most from the climate crisis. Despite this, our response so far has been minimal. We still regard climate change as some abstract, far-off problem, rather than an immediate existential threat. We don’t know how to deal with problems, or don’t care to deal with them, if we can’t see their concrete implications in the present.

But reading the IPCC report, and the storm of press around it, made the crisis real for me in a practical, and deeply personal, way: given what’s coming, should I be having kids?

The first is that not having a child is the most significant way of reducing your carbon footprint. A 2017 study found that having one fewer child reduces a parent’s annual carbon dioxide output by 58 tonnes per year—over 24 times more than the next most effective measure, going car-free.

The second reason, and the one I’m more personally inclined to, is that it seems like the ethical choice to make. Looking at the status quo, I doubt my children will inherit a planet that can support their existence, or any sort of life worth living.

Like most of Rice’s readers, I’m a millennial. This means my children, should I have any, will be adults during the second half of this century, when the worst ravages of the climate crisis will be in full swing.

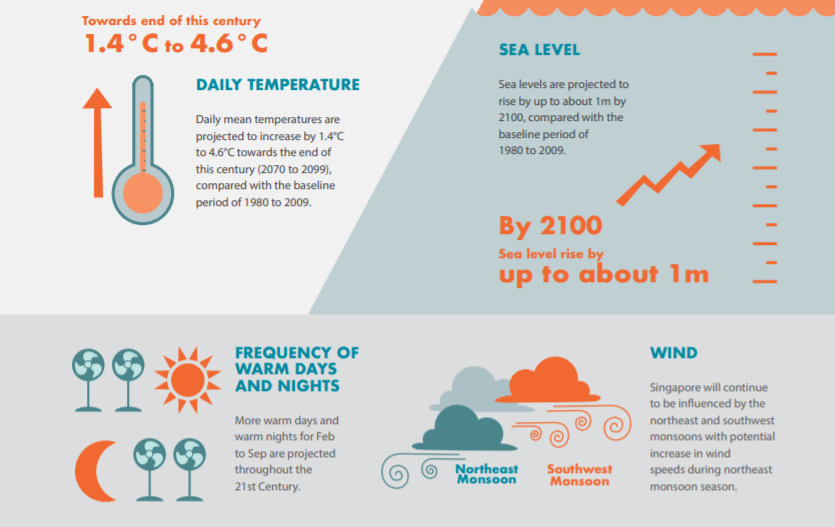

Extreme temperature rises, triggering heatwaves that would render huge swathes of the planet unliveable. (In Singapore, these are forecast at anywhere between 1.4—4.6°C by 2100.) Melting ice caps that send sea levels rising (in Singapore, by up to 1 metre) and devastate coastal cities. Drought and water scarcity, as the world’s freshwater supplies dry up and groundwater deposits are drained into oblivion. (Remember how most of our water supply is imported?) Famine and food shortages, as rising temperatures decimate crop yields. (Remember how virtually our entire food supply is, too?)

Instability. Economic collapse. Poverty. Chaos. War.

The outlook is dire, and all the more so given our current apathy. But even if I’m wrong, and we manage to slow the collision course we’re on, it’ll probably be too late for me to have kids by then.

For those of us not already parents, or still undecided about kids, biology means we don’t have the luxury of time to wait and see. The ten-year period we have to do major damage-control—if we even manage this at all—is roughly the same amount of time before our fertility windows close.

But the climate crisis is prompting a handful of young Singporeans to reconsider having kids. One of them is Yuxuan, who manages Back To Ground Zero, a local environmental group.

“I’m not absolutely certain, but leaning towards a big NO,” she said. “As a self-proclaimed environmentalist, I think the best contribution I can make towards the Earth is to not have a child that would contribute to ripple effects of environmental consequences with their every action, even just by breathing.”

“Additionally, our planet is facing a crisis that will render it unlivable in the future. I hope not to bring a child into the world, only for he/she to suffer from the extreme climate, limited land space, and no opportunity to enjoy the beautiful landscapes and diversity of wildlife.”

Meanwhile, Isabel, a teacher, is one of the decided few.

“Underestimation is a very real human flaw, because what we cannot see or feel we don’t understand, and what we cannot understand we are given to dismissing,” she told me.

“Over time, it gradually became clear to me that ethically, it would not do to bring a child into a world that cannot promise it a future, no matter how much money or love you shower on it in your lifetime.”

I carry a reusable water bottle and almost never take plastic bags with purchases, but that’s about it. Despite having had it on my to-do list for ages, I haven’t started carrying tupperware or reusable cutlery with me. I sleep with air-conditioning, buy cai fan that comes in a styrofoam box, wear clothes bought from fast-fashion outlets. and use cosmetics that come wrapped in layers of packaging.

There are so many less drastic steps I could take, but haven’t.

Part of this is my own shameful lack of willpower. But at risk of sounding like I’m making excuses, part of me wonders how much difference anything I do will make.

It’s not that individual actions aren’t important; it’s that it feels like they will never be enough to mitigate the damage. Not without concomitant economic, industrial, and policy overhaul of the kind we seem nowhere close to achieving. And not without a 180-degree attitudinal shift away from our quick-fix, throwaway culture, even though we face no penalties for succumbing or incentives to change.

“I do not think there is an acceptable amount of time left for ‘green education’ to take effect,” said Yuxuan.

“Although I personally remain hopeful and positive, and the eco-movement is gaining traction, there is only so much individual action can achieve. For example, just 100 companies are responsible for 71% of greenhouse gas emissions. If they were willing to change, think of the difference that would make.”

Isabel described how cultural disincentives hindered several of her and her friends’ attempts to ‘go green’. For example, they were rejected when they brought their own cups to bubble tea outlets, or scolded by hawkers for bringing their own tupperware. Meanwhile, many establishments still freely hand out disposable cutlery, even though they have seated areas for dining in.

“It’s tiring to fight against forces that are bigger than you,” she said. “It’s the idea that you can swiftly and easily clean up by throwing stuff away, rather than needing to stand at the sink and wash up. Or that you want the freedom to make a snap decision to buy a takeaway lunch on the spot. For every con you raise, I can easily find 3 reasons to justify throwaway culture.”

“Not when the world’s biggest corporations and leading economies refuse to do their part. Not when our government is urging us to slow down the rate at which Pulau Semakau is being filled, whilst structurally still encouraging such deeply entrenched practices.”

I don’t disagree with Isabel. In fact, I hear my own hypocrisy and frustration echoed in her words. The thing is, as David Wallace-Wells points out in The Uninhabitable Earth, blaming industrial capitalism does not name a villain, or at least one which we can slay and save the planet in a single stroke. It names a toxic investment vehicle which most of the world, you and I included, has bought into.

Extricating ourselves from this wreck means giving up a way of life that isn’t only familiar, but that we quite enjoy. It means butting heads with our optimism bias and our weakness for convenience and our breathtaking capacity for making excuses.

We are all complicit in this mess, and responsible for figuring out how to clean it up. But in the event that we can’t, I couldn’t bear for my child to suffer for it.

First is the fatalism this view seems premised on. Having children is fundamentally an act of hope; to believe, above all else, in love, and the resilience of the human race, and our willpower in facing down the odds—to do, and be, better than we think we can. To decide not to have them feels, in an indefinable but devastating way, like giving up; to accept that nothing is going to save us from our own pigheadedness.

Naked pessimism is not necessarily problematic, but it becomes harder to justify when it’s unproductive. If your house is on fire, you don’t just stand by and let it burn. No problem in human history was ever solved by letting it happen. (Though isn’t that exactly what we’re doing now?)

The best I can say is that the options aren’t mutually exclusive. Deciding not to have children is not incompatible with taking action to fight climate change in the present. You can take steps to save your house while evacuating the neighbours. The morality of bringing a child into an inhospitable Earth is quite separate from whether it is a constructive choice to make, all other alternatives considered.

Third, much as this will probably never become a mainstream view—not to mention that birth restriction becomes draconian and arguably immoral, when mandated as policy—if more young Singaporeans felt similarly, the consequences of this would be severe. (It would also be ironic, given how we were just named the best country in the world for kids.) Much as having children is not a national obligation, our ageing population, impending silver tsunami, low population replacement rate, and reliance on human capital mean we really can’t afford to find more reasons to not have them.

But isn’t that what you’re suggesting?, some might argue. You’d rather let the human race die out, than give birth to the people who could have the ingenuity—or add the necessary political pressure—to fix things?

In my view, this is just as cynical: it treats children as a means to an end.

I’m not qualified to say what a legitimate reason for having kids is, but I do feel certain about this: you shouldn’t have them in the hope that they’ll fix your problems for you.

“I feel pressure from familial and societal expectations, my own maternal desires, and anticipating the possibility of elderly loneliness in the future,” agreed Isabel.

“But in the bigger picture, I think I can bear this out with a much clearer conscience than if I were to have a child who must suffer, only because I once made a decision to bow to external pressures.”

History is full of failed warnings from doomsday prophets. In the 1800s, Thomas Malthus, an English economist, predicted that overpopulation would result in food shortages and famines, to the derision of Western Europe. In 1968, Paul Ehrlich, a German scientist, revived Malthus’ warnings, having failed to foresee the technological advances which would intensify agricultural productivity. (And of course, there was a time when people said that Singapore wouldn’t make it … but we did.)

Moreover, people have been having children in unfavourable circumstances for as long as the human race has existed, through poverty, plagues, war, and infinite kinds of hardship. No parent is ever certain their child’s life will turn out happily. To have a child is a gamble; an act, in some ways, of hubris as much as hope.

When I think of my parents, bright-eyed and newly married in October 1988, I can’t imagine they felt sure my life would be prosperous. How could they guarantee this? But they must have had a certain baseline confidence, not just in their ability to raise me, but that things would be okay, as they often turn out to be. That the world, however difficult and unkind it might be at times, would never actually be hostile to my existence.

Unlike my parents, I don’t even have that confidence.

It’s not about whether I’m secure in my ability to provide for a family or to be a good mother. It’s that I think the world my children will be born into will be unrecognisable from the one we live in now, and nothing I could do, no amount of love or money or sacrifice, will be enough to protect them.

I would be relieved—delighted, even—to have to eat my words one day. But right now, looking at the evidence, and the likelihood that we will act in time, it seems safer to shelve my dreams of motherhood.

Perhaps this is easier for me to contemplate because my feelings about motherhood have always been murky. Children have never been a must for me, and I wouldn’t regard my life as incomplete without them.

But because of my ambivalence, I’ve always known that if I ever have them, it’d be because they were fiercely, unequivocally wanted. I would love my children more deeply and more ferociously than anything, ever, always.

But love isn’t enough. I cannot protect my children from the future. I cannot promise them the Earth.

For this reason, and though my heart aches to type this, I probably won’t be having any. And we have to act now, right now, to save ourselves, and do right by children already living.