Disclaimer: RICE does not endorse or support any political party in Singapore.

Singaporeans seem to disagree on whether her comments were actually divisive. Some netizens told her not to “drag Jamus Lim into the mud with her” and called her a liability to the WP. Others stood by her—the hashtag #IStandWithRaeesah is still trending on Twitter, and she has received an outpouring of support on her Facebook page—and some thought that she didn’t need to apologise because they didn’t find her comments harmful to begin with.

This incident has made it clear that Singaporeans still don’t know how to talk about race.

It isn’t the first time Singapore has found itself confronting comments or actions that allegedly stoke racial and/or religious tensions. But the fact that past incidents have all varied in terms of severity, backlash, and consequences shows just how blurry the parameters of what constitutes a “racially divisive” comment can get.

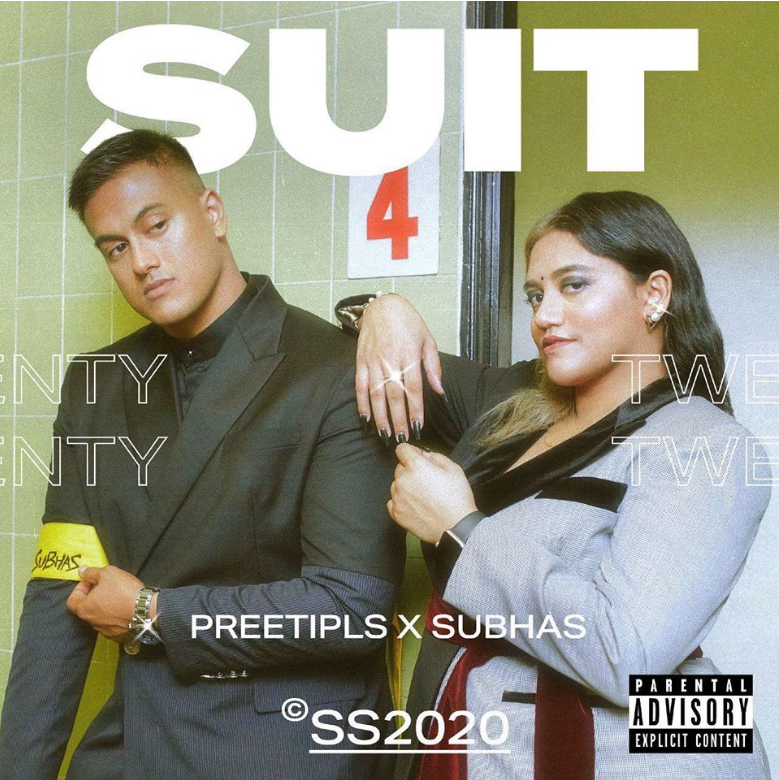

For instance, siblings Preetipls and Subhas Nair apologised for “targeting the Chinese” in a video they posted in response to a NETS ad which used offensive caricatures of minority Singaporeans. NETS also ended up apologising for portraying races in an “insensitive fashion”.

Other relevant incidents: a group of ex-Raffles Institution students publicly apologised for using blackface, as did Toggle. Socialite Jamie Chua has also apologised after making racially charged comments about Indian workers.

In some cases, however, a public apology didn’t seem to be enough.

Recently, a Temasek Polytechnic student was arrested after posting on Instagram about a dream where he was “gunning down anyone that’s relatively brown and non-Chinese looking”. His Instagram story was widely circulated on social media, and multiple police reports were made about how his comments incite hatred and violence.

As for Raeesah Khan’s comments, they fall under Section 298A of the Penal Code. In a nutshell, if you “knowingly” say or do something that might harm Singapore’s racial and/or religious relations, you can be jailed for up to three years.

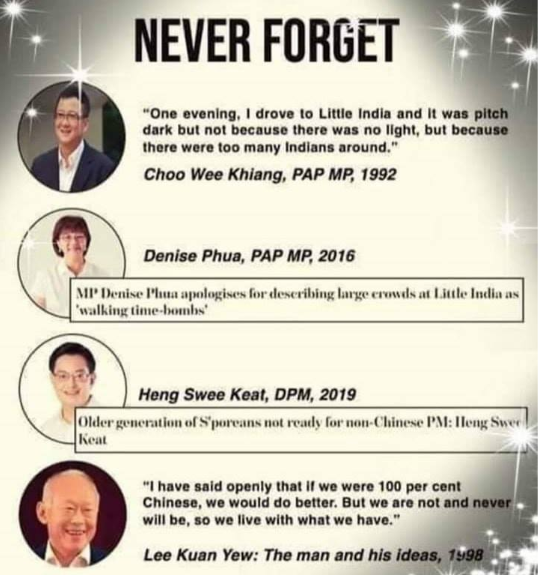

The furor over the incident suggests that “racial divisiveness” often comes down to a matter of perspective as well. If you talk about race and frame it in a certain way—for example, as an issue of pragmatism—some people find it racist while others do not.

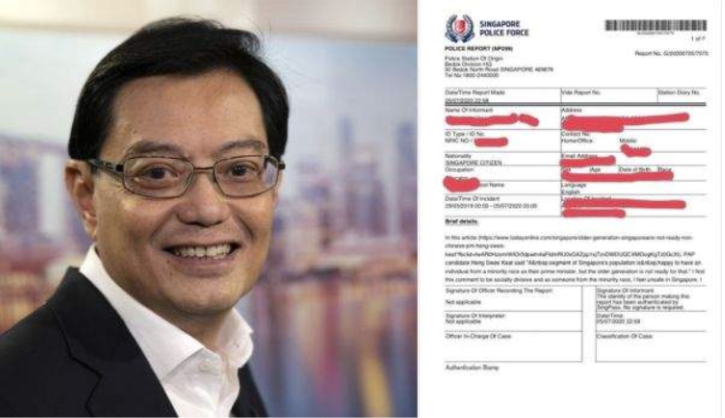

For instance, many took issue with Deputy Prime Minister Heng Swee Keat’s comments about Singaporeans not being ready for a non-Chinese Prime Minister. Even Lee Kuan Yew has been criticised for making offensive statements.

At the same time, these debates about what constitutes a “racially divisive” comment are often problematic and unproductive, dominating the discussion and overshadowing important conversations about how we can actually address racism.

In the wake of the police report made against Raeesah Khan, many minority Singaporeans have taken to social media to voice their frustration. Many minorities in Singapore feel “suffocated and tired”. They point to the microaggressions and systemic inequalities they’ve experienced all their lives.

What then, is the point of saying that someone like Raeesah Khan might be promoting racial enmity? Do minority communities in Singapore not already feel sidelined to begin with?

It’s hard to say. Because whenever an incident like this happens, a report is made, there’s a bit of uproar, and then everything falls silent once again. We never actually get to have a proper dialogue about race, racism and what multiracial harmony means to each of us because we’ve been conditioned to be so afraid of talking about these issues.

When this happens, the lived experiences of minority Singaporeans get erased.

In the case of Raeesah Khan’s comments, many have seen it as merely pointing out the lived realities of minority communities in Singapore. What one person considers ‘talking about race’ might be seen as ‘racist’ to another.

This isn’t 1964 anymore.

In order to start these conversations, we need to come to a new consensus on what we can and cannot talk about: what’s considered “racially divisive”, what topics are out of bounds, and whether we should re-evaluate our current OB markers. If it isn’t already evident, our idea of racial harmony needs to evolve beyond wearing each other’s ethnic costumes on racial harmony day.

And, hopefully—this is the idealist in me speaking—when we’re able to have honest, productive conversations, they will manifest in tangible policies that actually examine and correct existing inequalities.

Have a lead for a GE related story? Send it to community@ricemedia.co.