All names have been changed for privacy purposes.

Disclaimer: RICE does not support or endorse any political party in Singapore.

Charles, 28, is on the prowl for a partner on dating apps like Tinder and Coffee Meets Bagel. While he appreciates that the elections have “provided a common topic to talk about”, he also thinks that it has made him realise that people are more uncommon from one another than he used to think.

“When I tell people that I’m a fan of the PAP, sometimes I get blocked immediately,” he grumbles. “Before the elections, this never happened.

“I’ve also seen some profiles which say, ‘PAP supporters, swipe left.'”

Of those who bat for a different party, most actually want to understand his beliefs and debate with him, Charles clarifies. But when that happens, his chats shift in tone. They go from flirty to dispassionate—from an episode of Too Hot To Handle to a paper written by the Institute of Policy Studies—and cautiousness creeps into the conversation.

“Once we enter PAP territory, it’s as if romance dies and my matches see me as a curiosity, some kind of fossil.

“But surely people can date beyond party lines?”

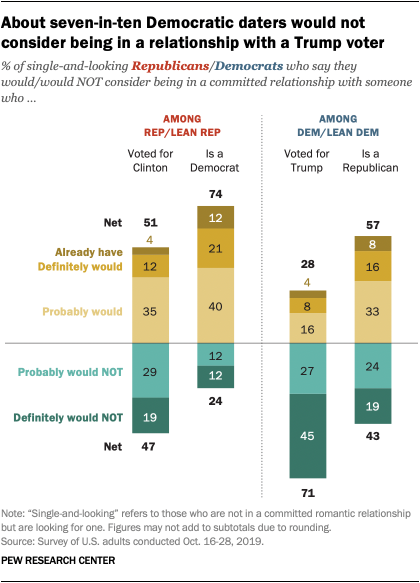

A Pew Research Center study conducted in February this year found that 71% of respondents who identify as Democrats or have favourable opinions of the Democratic Party probably or definitely would not want to be in a relationship with someone who voted for Donald Trump. Conversely, 47% of Republicans or Republican-Party-leaning respondents share the same view on their Clinton-voting peers.

Things aren’t that different across the pond. Over in Europe, a survey that dating platform eHarmony ran discovered that differing opinions on the Brexit vote “led 1.6 million Brits either splitting up with their partner or failing to progress things with a date”.

Moreover, political affiliations do not only determine how well people get along with each other, according to a psychology study. People tend to rate potential dates as less attractive if they have different political viewpoints, even though—and this is the crucial part—“they do not actually perceive them as such”.

In other words, if someone who dislikes the Workers’ Party encountered Jamus Lim, in his previous life as an economics professor, they might find him irresistible. But in the context of the elections, their cognitive biases take over and they would tell themselves he is an ugly caricature of a politician even though he is, objectively speaking, the Vitruvian Man come to life.

The study concludes: “people may have rated targets as less attractive to convey their dislike because of [the targets’] support for a particular political candidate”.

Politics, then, is inextricable from the way we relate to people, down to the most fleeting of first impressions. A handsome face will not save you from being swiped left if you profess to support a political party that another dislikes.

As Charles himself admits: “Actually, I’m grateful for all the girls who list their political affiliation on their profiles—and there have been a lot lately because of the elections … I just swipe left. It saves me a lot of time.”

“It was quite shocking to see what some of my friends were saying [in my Whatsapp group chat],” Gina, a 30-year-old lawyer, says. “One accused Raeesah Khan of wanting to destabilise Singapore by importing Western ideas. Another defended Ivan Lim, saying that personality should not matter as long as he does his job well.”

“If that’s the case then we should give Harvey Weinstein a second chance,” she adds drily.

Gina grew so exasperated with what her friends were posting that she pointed out all the flaws in their arguments. Her comments opened the floodgates and her friends split into two factions, turning the group chat into Berlin of the Cold War.

After polling day, Gina decided to extend an olive branch and asked everyone out for a meal, hoping that the years they spent together in law school would tide them through this argument.

It’s been five days; no one has replied. One has left the group.

To answer these questions, it’d be useful to turn to research done on the most pervasive form of discrimination: racism.

Yes, racism is caused by a complex interplay of historical, structural, and individual factors. At the same time, the root of racism can be distilled into a “super simple” reason, according to Jennifer Richeson, a psychologist at Yale University.

“People learn to be whatever their society and culture teaches them … It comes from the environment, the air all around us.”

Transposing this explanation onto the “society and culture” in Singapore, it becomes apparent that one culprit—among many others, to be sure—of political intolerance in society is the toxic air that blew across the nation a week ago.

In a Facebook post reflecting on the election results, Ex-MP Inderjit Singh characterised the PAP campaign as being “focused on discrediting individuals on the opposition camp rather than discrediting their manifestos”.

As a resut, many people interpreted the PAP’s campaigning strategy as one fuelled by “personal attacks, name calling and character assassination”.

Taking their cue from the campaign strategy of the ruling party, “many PAP friendly sites who are likely PAP IBs [internet brigade] were hitting below the belt and resorted to character assassination instead of having an intellectual argument of ideas and policies.”

I list these examples not to repeat the dirty tactics of the elections (of “hitting below the belt and … character assassination”), but to point out that the rhetoric used by political parties and leaders bleeds into everyday interaction in society.

When people who examine structural discrimination are accused of “promoting enmity between different groups on grounds of religion or race”, when people with different opinions are slandered because they “cannot change, and will never change”, relations in society take on this distorted shape as well.

In other words, an election campaign—and, more broadly, political discourse—characterised by intolerance, and portrayed as a zero-sum game, inevitably affects the way people relate to others of different political beliefs.

I mean, if you see your parents shouting “fuck” at everything they dislike, you’ll naturally internalise the idea that it’s okay to do so, and start yelling at every knnccb si gina who challenges your beliefs.

And, as Gina and Charles have discovered, society—on the very micro level of friends, partners, and even family members— is worse off for it.

“I didn’t realise politics were so divisive. Is this what it’s like to grow up?”

At that moment, I nodded empathetically. This is why you don’t talk about politics over the dinner table.

But now I wonder how much of it is learned helplessness: was I, like everyone else, so enmeshed in the toxic system, this false dichotomy, that I have taken for granted that politics causes divisions, factionalism, tribalism?

Perhaps it’s me being idealistic, but I believe that politics can also bridge divides. Just look at politicians like Tharman Shanmugaratnam, Tan Cheng Bock, Low Thia Khiang, Louis Ng. They allow us a peek at how grown-up politics in Singapore can be conducted.

Contrary to what Gina said, it’s not growing up, then, that makes us realise politics is divisive. It’s that we—and our political climate—have yet to grow up, are prevented from growing up. So instead of having rational, mature debates on politics, we unfriend, unlike, insult each other. Just as we used to do in primary school.