Because patients with Covid-19 are not allowed to reveal their identities, this account was related to our editor, and has been written in the first person.

A Trip to Europe & the Covid-19 Test

When I left Singapore for the Netherlands and Germany on March 6, the two countries didn’t have a significant number of Covid-19 cases*. This work trip, in the planning for many weeks seemed important, even if in the end, nothing worked out as planned.

Nobody in Europe anticipated that the situation would escalate so quickly. People either behaved very confidently, like, “hey, the virus will never attack me”. They were swinging dicks and minimising the problem. Or they felt helpless, overly concerned, but acted without any common sense.

On the afternoon of March 19, at Tan Tock Seng Hospital, the results looked good and the doctors were reassuring. They said that I am most likely okay. So I head home feeling positive and go to bed early. During the night I have body aches and only fall asleep towards the morning.

March 20: You Have Covid-19

When I wake up at 10:30am the next morning, I see that I have 9 missed calls from an unknown number. My first thought is that this must be ICA to check if I was abiding by the law and serving my Stay-Home Notice.

I call back immediately and find out that it is the hospital. They are very friendly and tell me that my results are positive.

They tell me that I have one hour to pack before an ambulance comes to pick me up. They are kind enough to tell me what to pack: my phone, charger, laptop, books….and that I would be in hospital for about 1-2 weeks. I drink three glasses of soy milk, the only food I have at home, and get ready. I don’t feel special or particularly concerned. I feel grateful that I now know I have Covid-19 and that I am in a place where people would take good care of me.

Telling Friends and Family That You Have Covid-19

Everybody is very concerned but most friends react maturely. I have to inform all the people I met during the two weeks of my trip. Some feel very anxious and I have to repeatedly reassure them and describe my symptoms, share what the doctors said, etc.

No one wants to be associated with the virus.

It feels as if many are more worried about what I am now going to do with all this free time, than being concerned about my health. I receive a huge amount of entertainment tips, Netflix recommendations, Ebook links, and pictures of my friends’ activities outside. It’s interesting and overwhelming at the same time, even if I know that it’s coming from a good place.

I have never been bored in my life. I think I would rather observe what is happening and, if possible, enjoy the new experience, instead of covering it under a layer of light entertainment.

March 20-22: Warded at Tan Tock Seng Hospital’s NCID

I am in a ward with E, or case #376. She is a 21-year old PR with an American father and Indonesian mother. She grew up in Singapore and has come back from the UK, where I think she was studying. We’re both tired and we can’t communicate much. A latent feeling of guilt floats through the room—both our cases are imported from overseas.

I express it to one of the doctors who laughs it away. She is friendly and tells me, without saying it expressly, that she doesn’t think in these categories and that she doesn’t judge me. She makes me feel better.

E is often on the phone with her family. She has a runny nose and some congestion. I had a slight fever, 38.2 on one evening, but that’s it. I just feel such immense fatigue and body pain. Some of us have no symptoms at all.

Time is so flexible. Space too.

And Singlish counteracts the sterility.

Having time and occupying little physical space feels perfect to me.

Friends and family from the three locations of my Singaporean, French and German homes are now at the same distance. All equally out of reach but not out of touch.

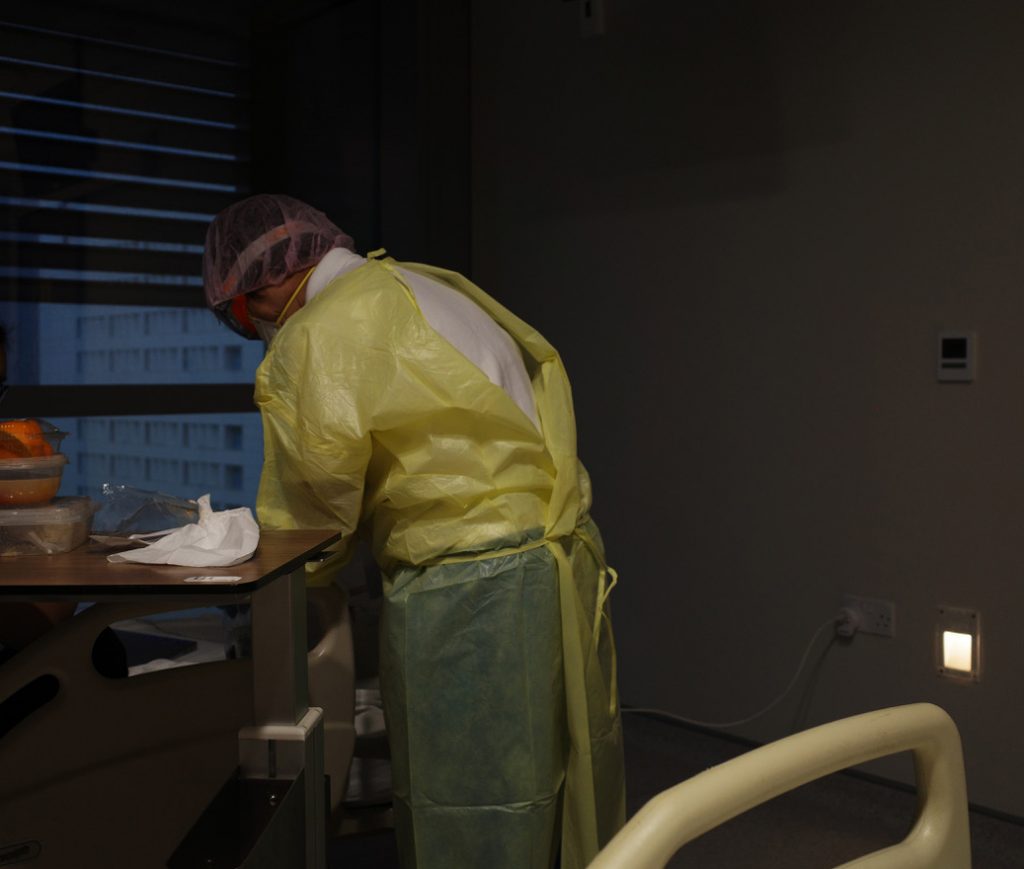

Above their sky blue trousers, white t-shirts and black shoes they are wearing thin yellow plastic coats, rose-coloured hairnets, huge Uvex goggles, masks in white or green colour and mid-blue gloves.

The rustling of all these plastic sheets gives me the shivers, especially in the middle of the night.

They drag blue devices with red digital eyes along to measure our blood pressure and pulse. These devices look like little animal companions in a children’s zoo.

Touch has now become a high risk gesture whose necessity is carefully weighed.

The yellow coats too are discarded, and all the other things that we have touched. The blood pressure pets are fully disinfected before leaving the room. The sliding door slowly closes again.

It is a strange feeling to involuntarily impose these strict measures on those who take care of us. They work so hard that we don’t dare to ask for more.

The testing begins and it is a nose swab.

It’s awful and quite painful if you stop breathing because your nostrils close then. They poke a sort of thin pipe cleaner into both nostrils to take samples from the back of your nose.

They need to do this once a day because the sooner we test negative, the sooner they can discharge us, and free up beds for the more serious cases, or for the ones who are newly positive.

March 20-22: Jerome/Jérôme, the Covid Tracker

Jerome, who tracks Covid-19 cases, calls me several times per day.

He just called again.

I like that every conversation starts with: “Hi, this is Jerome.” He has a mellifluous voice and I imagine him handsome. I somehow want to spell his name in French, Jérôme. I manage to make him laugh, despite the seriousness of the situation.

He often starts a sentence and I complete it: “so you got home and unpacked… exactly and also did my laundry.”

It’s a bit like reporting to a lover who is far away and wants to imagine and share your life, feelings included. My routine, taking place within the four walls of my apartment, are of course irrelevant, but we talk about them seriously too.

Jérôme no longer feels like a stranger, he is my covid pal and detective fantasy. He told me that I am case #362 this morning.

He is intelligent and maybe a fictional character. I hope he calls again tomorrow. I want to understand the pattern for when he uses the landline, and when my mobile phone.

Sometimes he asks the same question on both lines.

Now, he has my email address too, because of the disinfection guide which I will receive shortly.

Will he write a personal note to go with the instructions?

He has my postal address too and remembers my postal code by heart. When I get stuck after the first two digits, he completes the rest elegantly, and with a delicate laugh.

It looks like the virus mainly affects my fantasies and allows my imagination to go wild.

The Next Day

Jérôme called again.

On Sunday at 5.25pm.

I recognise his number and wonder if I should not save it under his name.

His voice sounds young and today he sounds a bit tired.

“Hi, this is Jérôme.”

I want to say, “Hi Jérôme, I was waiting for your call”, but keep quiet.

“Can I check your passport number, please?”

“Sure, give me some time to get it.”

I feel embarrassed again. Why was I not able to remember my own passport number?

My roommate is sleeping and the lights are out.

I ask him: “Do you always work on Sundays?”

Now he seems a little embarrassed, not expecting me to have an interest in his life.

“These days we work a lot, almost all the time”.

We agree that these are exceptional times. I wish him a good rest of the day and hang up.

I then remember that I had given him my passport number before, during our first conversation. When I gave him the number he always repeated C like Canada? N like Norway? Maybe his handwriting is messy and he needs to verify it again.

He’s sent me the disinfection guide. It came as an attachment to a nicely written email that started with: “Hi Ms_______” and ended with “Get well soon! Regards, Jerome”.

So long Monsieur Jérôme, I hope we can continue this conversation and maybe expand it to other subjects in the future.

I feel so incredibly tired today but you tracking me makes me feel ah, so special.

On Monday March 23, we’re told we will be moved in the late afternoon, around 5pm. We are the last batch of 29 patients who will be transferred from NCID to Mt. Elizabeth.

All of us are quite fit. We are told that the fitter patients will be transferred to give up their beds for more critical patients, as the hospital anticipates the numbers will go up.

There are seven young women in the ambulance and we are escorted by a motorbike. Several were studying overseas.

They have to finish their semesters from here (now that the universities are closed, it will be complicated).

One was planning to participate in a programme in the US which is unlikely now. Others were going to see their partners, families.

The fact that no one knows how long it will last makes the situation difficult.

We don’t have much time to talk to each other, but I get the feeling from this group that everyone had a serious reason to be overseas.

They weren’t just going there on a holiday.

March 23: At Mt. Elizabeth Hospital

At first, it looks like there are no windows in my room.

Then I realise that the black wall is a window, which overlooks a grey courtyard. Buildings loom close by and the room feels hemmed in.

I share this room with S, or case #256. She is from Manila.

She works in Singapore in an airport logistics company and has been based here for 7 years (if I remember correctly).

She got infected by her flatmate and has been in hospital since Monday 16.

I interact more with her. She continues to work for her company. We also have to resolve room problems together (the aircon!) and we dream of a glass of alcohol.

Mt. Elizabeth feels like a plan B to keep Covid-19 patients in hospital.

The doctor comes every morning to do the swab test. There are nurses who occasionally check our temperature, pulse, blood pressure.

When Everyone Resents You For Being An “Imported Case”

Everything has gone so quickly and I feel quite isolated. Of course I have heard that the number of cases have gone up because of these overseas imports.

I know I am one of them.

Yet people like Jérôme spend their days mapping journeys and reconstructing stories.

So every moment and movement seriously matters. Borders are blocked, nationalistic sentiments are understandably expressed.

Friends in Europe want confirmation that I brought it from Singapore.

When the virus first began spreading, I got this sense that Europeans thought of it as an Asian problem, far away.

Then it shifted and I realised how unequipped, helpless and naive they were.

Singaporeans want it the other way round—I am the European who brought it from Europe. The virus seems to have distinct nationalities, while I find it hard to define my own.

The Situation Has Escalated And Now It’s Lockdown

Here is another reason I went to Europe—I decided to go and see my family on the weekend before work began.

This opportunity turned out to be the last to see my father. I am grateful that I got this chance. Not being able to move can be tragic. It’s difficult to judge others’ movements.

March 26: Still Here, Still Waiting

That’s good news. Maybe I can see the sky from there—pink, blue or black.

And maybe Jérôme will call.

Did you test positive for Covid-19 and want to tell us your story? Write to us at community@ricemedia.co.