Top image by Zachary Tang. All other photography by Liang Jin Tey.

Here’s a list of things that Singaporeans have thrown down the rubbish chute in just the past year: shards of broken glass, a variety of curries and soups, half-extinguished cigarette butts, a blood-stained shirt from the Orchard Towers murder, and a newborn baby wrapped in a plastic bag, who miraculously, survived the ordeal.

Admittedly, these are extreme examples of incidents that might happen anywhere else in the world, but it does serve to highlight the role that the rubbish chute plays in the Singaporean psyche.

I imagine the internal monologue to go something like this:

Once I throw this item down the chute, then this never happened and it’s not my responsibility. The consequences of my actions are out of sight, out of mind. Somebody else’s problem.

Arguably, this is also the reason why eco-initiatives promoted by government agencies have come and gone, rarely achieving widespread adoption.

Because why should I care where the nearest recycling bin is, when a rubbish chute has been built right into my kitchen? So what if NTUC wants to charge me five cents for a plastic bag? Some families are perfectly willing to order a month’s supply of bags—just so they can use their chute.

This indifference is borne out in the numbers: Singapore’s domestic recycling rate has plummeted for four years in a row: from a ‘high’ of 22% to 13% in 2020. This despite there being a robust recycling infrastructure in place; the recycling rate for the private sector is 68%.

And therein lies the problem. Singapore will never meet its ambitious green targets if they are unable to address the root of the issue:

That the rubbish chute has desensitised Singaporeans from the consequences of their waste.

The Legacy Chute Needs An Upgrade

The Singaporean rubbish chute is very much a product of its time. When it was first built into HDB flats, it instantly became the most efficient way to collect and manage waste, replacing the manual labour of ‘karung guni’ (rag and bone) men, a group of workers who would sort and collect Singapore’s rubbish from household to household.

Unfortunately, this efficiency has also made Singapore a victim of its own success.

The system now works so well that households never have to think about their waste at all. By building the rubbish chute into HDBs, the government has unwittingly ingrained behaviours and habits that have now become almost impossible to change.

These habits have also translated into a self-justifying mentality. Some Singaporeans vehemently believe that there is little value to recycling at all. Many locals I’ve spoken to opine that it doesn’t work, and even if it did, Singaporeans won’t do it properly anyway. So what’s the point? Some believe that Singapore’s waste incineration strategy and waste-to-energy technology will be a cure-all, rendering household recycling obsolete.

Ironically, this was the same line of reasoning that Singaporeans used for face masks early last year (i.e. “they don’t work, people won’t wear them properly, safe distancing and hand-washing are better alternatives”). Then the migrant worker dormitory crisis happened, masks were mandated, and those arguments disappeared overnight.

Do we have to experience a comparable environmental crisis for Singaporeans to finally come to their senses?

If not, what’s the solution?

A Team of Young Singaporeans Are Trying to Tackle the Problem

To understand how to tackle this uniquely Singaporean problem, I turned to the team behind Waste Less Smart Chutes, a group of secondary school friends who have interesting ideas around how to update the rubbish chute for modern Singapore.

The first step was to see the Smart Chute prototype in action. We traveled to NUS, and crammed ourselves into a hallway of Tembusu Residential College, where the Smart Chutes had been installed.

These weren’t ordinary rubbish chutes. For starters, there were three of them: one for general waste, one for paper, and one for plastic. To access the chutes, all residents on the floor were required to scan a unique ID card against the external sensor. Behind each chute was a digital scale, which weighed the waste and recycling as it was being deposited.

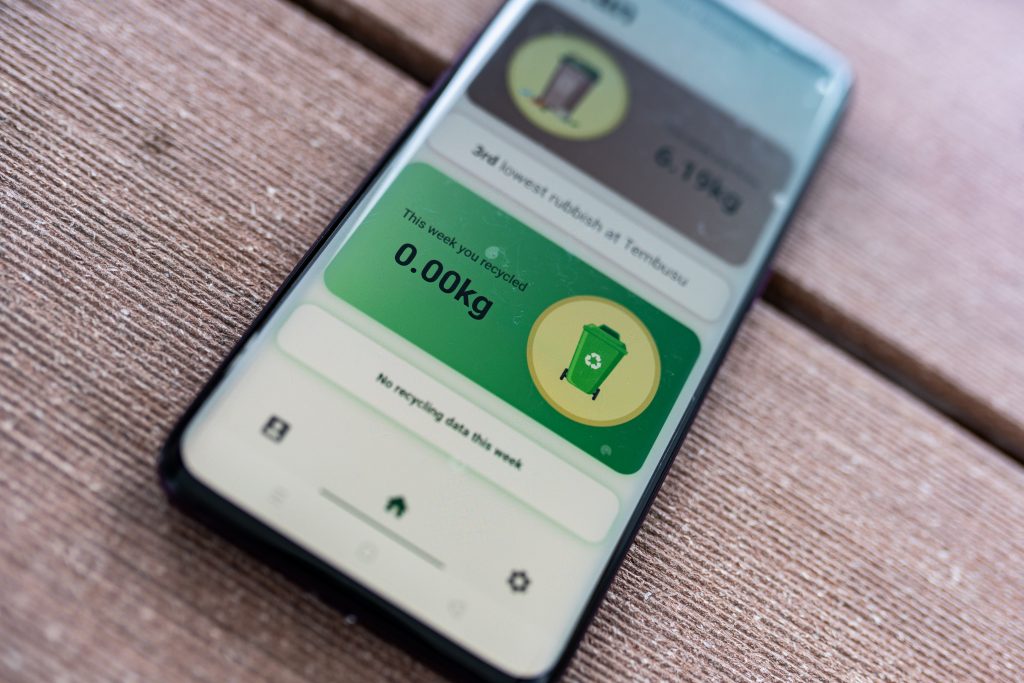

The data would then be transferred to a mobile app, which the team coded themselves. Here, residents could track, in real-time, their own waste usage against past weeks or months, as well as against other residents on the floor. There was even a leaderboard.

Currently, this is only the existing prototype of the Waste Less Smart Chutes in Singapore. The idea for it started off as a couple of slides on a PowerPoint, submitted to the NTU Impact Through Inspiration ideathon during circuit breaker last year.

As one of the finalists of the competition, they caught the interest of one of the judges, who became their mentor, helping them to engage with stakeholders like NUS, and securing funding from Southwest CDC to install their first prototype.

“None of us started with the concept that we wanted to fight for sustainability. It was something we kind of fell into,” said Anthony Sukotjo, 22, one of the team’s software developers.

Smart Chutes was the ‘crazy idea,’ dreamt up by this team of young Singaporeans, all between the ages of 21 and 22.

As Gen Zs, they are practical enough to see the problems they’ve grown up with and the solutions that have already been tested, but idealistic enough to think that more can be done.

After we inspected the chutes, I sat down to interview the three core members of the team, Anthony Ardi Sukotjo (22), Neo Yew Chong (22), and Pradeep Mani Rathnam (22), who served as the team’s unofficial spokespeople.

“So what’s next after this?” I asked.

“Honestly, we’re not sure,” said Anthony, “None of us thought we would make it this far.”

What Singaporeans Are Motivated By

“Singaporeans do value convenience a lot. We’re … not willing to walk very far,” said Yew Chong.

But there are two things that Singaporeans value more than convenience: money and a good deal.

Take the reverse recycling vending machines in Tampines Hub as an example. Initially, the monetary incentive was set at $0.20 for every four bottles Singaporeans deposited into the machine. This resulted in massive queues around the block.

When the government adjusted the incentive to 20 bottles for $0.20, the queues disappeared.

Case studies like this helped to inform the design principles behind the Smart Chutes.

“The issue with any new incentive system is that there is always a way to game the system. If Singaporeans become overly reliant on incentives, then the behavioural change will only last as long as the incentives are around,” said Pradeep.

“With Waste Less / Smart Chutes, our focus is on changing behaviour by making hardware and software updates to a system Singaporeans already use, and are familiar with (i.e. the rubbish chute).”

The team drew inspiration from the LumiHealth national health campaign that the Government launched in partnership with Apple. The two-year initiative encouraged Singaporeans to hit 10,000 daily steps in order to redeem this for rewards and vouchers.

“That was an example of incentives done right,” said Yew Chong. “Most Singaporeans were already inclined to want to be more healthy and active anyway, so the incentives introduced were merely the ‘cherry on top’ to further reward such behaviour.”

Similarly, the Smart Chute was designed so that they wouldn’t need to go down the pure incentivisation route. The team is betting that armed with the right data, Singaporean household behavior will slowly trend towards waste reduction.

“As a team, we had to be a bit idealistic and a bit practical,” said Yew Chong. “For behavioural change, you can look at it like the S-adoption curve. In the beginning adoption is very slow, then you ramp up, until it becomes established behaviour.”

“I think in theory, Singaporeans want to be more sustainable,” said Anthony. “But the current infrastructure does not allow them to easily do so based on their time-crunched lifestyles. Even if you introduce more education on how to reduce waste, it can be difficult for Singaporeans to follow through.”

“Most statistics on Singapore’s waste problem are too high-level,” added Pradeep. “People can’t wrap their minds around how this applies to their own circumstances.”

“So the first step to changing behaviour is to empower people with their own data: this is how much waste you’re generating. This is how you compare with your neighbours. Generally, people are competitive. If they see that ‘oh, I’m generating the most waste on my entire block,’ this will nudge them to gradually change their behaviour.”

“Only then can public education campaigns achieve their intended results.”

The Singaporean Mindset Needs a Software Update

“Traditionally, waste is seen as something that is a byproduct of human activity. It is seen as something that we just want to get out of the way,” said Yew Chong.

“But in a truly circular economy there should be no concept of waste. All resources are just in different stages of use and reuse. The real paradigm shift we need to make as a society is that we need to look at waste as something that can be nurtured back into something of value again.”

For this to happen, fresh perspectives from younger Singaporeans are critical. For the Smart Chutes team, all of them grew up seeing the problems and practical constraints posed by the rubbish chute, and yet are idealistic enough to imagine a better solution.

“I think the attitude of the younger generation is that they feel like the world they are entering into has a lot of problems: the Covid economy, climate change and many other injustices around the world. Community activism is playing a bigger role for us,” said Anthony.

“This Smart Chutes project is simply our way of expressing our values, and translating it into concrete action that will hopefully impact society-at-large.”

Currently, the team is in active discussions with NUS, with hopes to expand their initiative beyond a single prototype. Their ultimate goal is to choose the course of action that maximises the scale and impact of their project.

“I think the overall theme for our generation is finding a purpose,” said Pradeep.

“Whatever work we do, it needs to have some meaning beyond just making money.”

Yew Chong agreed. “A lot of times, young people are afraid. They might have an idea, but they think, ‘I’m just a student, what can I do? Or I’m only one person. How can I make an impact? We’ve been going out of our way to tell people, don’t be afraid. If you think you can change something, you should go for it and try it out.”

In order for Singapore to truly ‘go green’, there needs to be a hardware update to the legacy rubbish chute, as well as a software update to the Singaporean mentality on waste.

Have thoughts about this story? Write to us at community@ricemedia.co.

And if you haven’t already, follow RICE on Instagram, Spotify, Facebook, and Telegram.