This week, as 140 cases doubled into 287, we were forced to take a sobering look at the dismal living conditions inside worker’s dormitories like S11 Punggol.

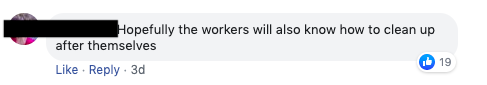

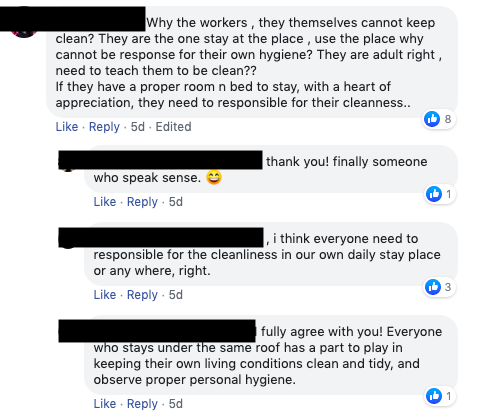

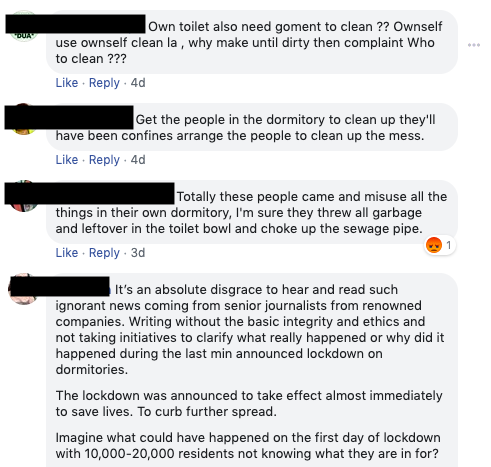

Two very different responses emerged. On one side, anger and dismay. On the other, people blamed the migrant workers themselves. The dorms were dirty, they argued, not because we have crammed too many people into inadequate facilities, but because the workers themselves are inherently disgusting and irresponsible. They have “different hygiene standards” from Singaporeans, and “they should learn to clean up after themselves”.

This is some next-level irony. Singaporeans telling migrant workers to clean up after themselves when they are employed here precisely because we cannot clean up after ourselves. As if our toilets and airports owe their gleaming reputation to some magical Singaporean instinct for hygiene, rather than a ready supply of migrant labour.

It’s hard to keep communal spaces clean. Harder still if the spaces are overcrowded and ill-equipped to begin with. Why we can accept this for public toilets in shopping malls, but not for public toilets in dormitories, I cannot say. However, I seriously doubt that 160 Singaporeans sharing a single toilet will somehow produce a radically different outcome. Last I checked, we are not a nation of rainbow-farting unicorns.

“Incurably filthy”

What should really dismay us is not the latest round of accusations, but how the idea of ‘The Filthy Migrant’ has persisted for centuries in Singapore. For as long as people have been immigrating to Singapore, others have been accusing them of disgusting habits and lax sanitary standards.

Many of the comments this week would not be out-of-place in 1843.

In colonial Singapore, the main target of such accusations were Chinese coolies, who came here to work— to die—in the thousands. Packed into airless shophouse cubicles, they succumbed to cholera, dysentery, tuberculosis, typhoid, smallpox, and a host of other infectious diseases. The conditions were so bad, coolies would often flee their lodgings when their colleagues began dying, or else they would dump the corpse unceremoniously for the police.

The response from the municipal authority was a mix of hand-wringing and racism. While some health officers advocated for reform, many others blamed the coolies instead of their living conditions. In Contesting Space In Colonial Singapore, Prof. Brenda Yeoh provides a thorough account of how blame was heaped upon the ‘asiatics’.

Sir David J Galloway, founder of the Straits Medical Association blamed many epidemics on the Chinese “talent” for “huddling together”—as if coolies were agoraphobics who preferred windowless shophouses to spacious mansions. He also claimed that “Chinamen” were “the most insanitary of mortals”. Chinese cities, which he had not visited, were nothing more than “instances of filth”.

Where it was not possible to blame just the Chinese, colonial officers broadened their criticism to a notion of “Asiatic insanitation”. Asiatic habits, like a dislike for “air in his dwelling-house”, and a “carelessness regarding the removal of excreta”, made Singapore a hopeless “pigsty”.

What’s remarkable about such filthy stereotypes was their total incoherence—even by the standards of the early 1900s. In one telling anecdote, our Dr Galloway condemns Muslims for their poor hygiene and accidentally criticises himself in the process. In his report, he writes that there was “nothing in the Mohammedan religion which tends towards sanitation”, citing “frequent ablutions” as an example of how the Muslims were contaminating the water supply.

So, the Chinese were filthy because of their “scant love for soap and water”, while the Muslims were filthy because they washed too often, and thus fouled up the water. There’s really no way to win this game, is there?

However, the British Empire was nothing if not an equal opportunities bigot. What’s interesting is how the stigma of filth shifted according to circumstance and necessity. When the Spanish flu swept through South-east Asia in 1918, it hit the Tamil migrant population in Malaysia particularly hard. The death rate amongst Indians was 83/1000, or more than double the mortality rate for Chinese or Malays.

The narrative shifted accordingly. The Indian migrant populace, which had previously been a ‘model minority’ in terms of hygiene and public health, suddenly found themselves under attack and transformed into filthy animals.

It was their “unhygienic eating and bathing habits”, alongside their “racial weakness” which accounted for the high infection rates. Perak’s medical officer, one Dr. J.W. Field blamed the death rates on the Tamil community’s “unhygienic and imbalanced dietary habit”, as well as their “natural indolence”. The colonial media likewise suggested that the Spanish flu had spread from “the Indian subcontinent via migrant workers”.

No evidence was ever found to support such a claim. In its panic, the British Empire even got its racial stereotypes mixed up. The ‘lazy’ Malay and the disgusting ‘Chinaman’ combined to become the lazy, disgusting Tamil. One wonders, of course, how these negative traits had eluded them before the pandemic. The reason should be quite clear: filth is never about filth, it’s always about politics. By blaming the flu’s spread on the ‘unhygienic’ personal habits of Tamils, it effectively absolves the government from blame and future responsibility.

Not only is it not their own fault they died, you also don’t have to address the root cause of the infection’s spread: overcrowded, poorly-built housing. After all, why make the “financial sacrifice” when “oriental stubbornness” and “hereditary Chinese instinct” will undo all of your good efforts by “clinging to dirt”?

You can’t fix broken people, so the colonial government never did. Many of the diseases remained endemic until independence.

“These People”

In conclusion: The Filthy Migrant is an incredibly versatile figure. Not only can he absolve you of your responsibility, he can also change his race/religion according to what you require. If your Chinese population is diseased, he is a Chinaman. If Covid-19 is spreading like wildfire amongst the Bangladeshi and Tamil S-pass holders, then he is an “irresponsible” man who “cannot clean up after himself” and has a “generally lower awareness of hygiene”.

Sadly, The Filthy Migrant does not actually exist—except in the racist imagination.

Some migrant workers are dirty. Some are clean. One worker I spoke to was utterly dismayed by the number of cockroaches inside his dorm. However, to label “these people” or any group of people filthy is plainly bad. Unfortunately, it is also very profitable, or else it would not continue. Such narratives of filth served the British well when they wanted to avoid costly public health reforms. That practice persists today. The Filthy Migrant is here so we do not have to shoulder the financial burden of reform; so the cost savings can be had and shared.

As the historical record shows, almost every group has been stigmatised at some point. The filth is not inherent to anyone. We’ve just failed to provide sanitary conditions for migrant workers—for approximately 200 years. We’ve celebrated the bicentennial, but we’ve yet to disown the beliefs we inherited from the British. And as the current crisis in worker’s dormitories shows, we’ve got a long way to go yet.

Tell us what you think of this article at community@ricemedia.co.

Contesting Space in Colonial Singapore: Power Relations and the Urban Built Environment by Brenda S.A. Yeoh

Terribly Severe Though Mercifully Short: The Episode Of The 1918 Influenza In British Malaya by Kai Khiun Liew

Tuberculosis: The Singapore Experience, 1867 – 2018, Disease, Society and The State by Kah Seng Loh and Li Yang Hsu