Top image: Marisse Caine/RICE File Photo

Associate Professor Tan Kok Yang remembers the time he broke a bleak prognosis to his patient—an 80-year-old man with advanced stomach cancer—and his family. The cancer had already spread to other parts of his body. Things were not looking good for the octogenarian. He had only six months to live.

I was dreading to hear the next part of this anecdote. In fact, I had not been not looking forward to my interview with the good doctor in the first place, who helms the General Surgery department in Khoo Teck Puat Hospital.

The 50-year-old senior consultant is also deputy chairman of the hospital’s Medical Board, and has been practising medicine for more than 20 years, specialising in colorectal surgery.

It was not because I was shunning healthcare workers amidst fears of Covid-19. Rather, like many Singaporeans, I am uncomfortable with discussing death. Many Singaporeans remain superstitious and regard death as an inauspicious and taboo subject.

For me, talking about death feels morbid, with negative connotations like fear, sadness, and pain attached. My aversion to the topic also stems from denial. Although I understand intellectually that the death of my loved ones is inevitable, it can be emotionally challenging to accept such an eventuality. I needed to cross this mental hurdle before feeling comfortable enough to even broach the subject.

Maybe this is why Prof Tan had a difficult time with that elderly man and his family. Perhaps, like many of us, they wanted to avoid talking about death. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

All three parties were gathered in the room of Prof Tan’s clinic in Khoo Teck Puat Hospital. The elderly man was intelligent and knew what was going on. He understood what was about to come. Prof Tan had examined him previously, and explained the reason he was doing it.

Yet, Prof Tan says: “The family was very adamant that this person should not know the diagnosis.”

“The family said, ‘Oh, he doesn’t need to know the diagnosis, maybe we ask him to leave the room first and then you tell us.’”

Prof Tan was not happy. His opinion is that patients have the right to know, and the man wanted to learn of his fate. “If I had only a few months to live, I would want to know. I would want to do things that I have been procrastinating,” Prof Tan says.

But the family intervened and insisted the senior should not know about it, and they would find out on his behalf. With tears running down his eyes, the old man looked at Prof Tan and his face gave it away. He looked at his family and said, very lovingly: “It’s okay, I don’t want to know. I will leave the room.”

After that clinic consultation ended, Prof Tan was overwhelmed with emotions and wept.

He saw that even in the face of death, the elderly man respected his family’s wishes. The man left the room, knowing that he did not have much time left, yet not knowing the specifics of his condition.

Such a scene could have been avoided, if Singaporeans were open to talking about preparing for death.

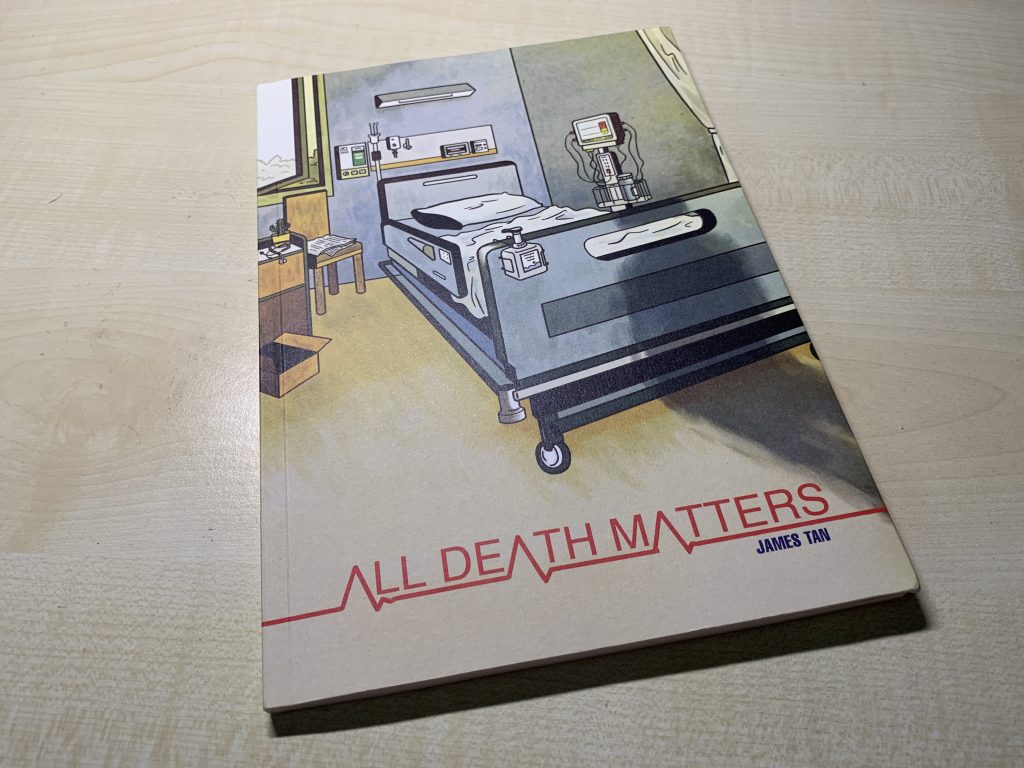

As much as I am uncomfortable with discussing death, it is a topic we cannot run away from. And the opportunity to raise this subject came when a graphic novel commissioned by Lien Foundation on palliative care was released earlier in March this year.

The 72-page book, written and illustrated by local artist James Tan, focuses on the role medical professionals play in helping patients cope with the dying process.

Although Prof Tan has had his fair share of breaking bad news to patients since he became a qualified surgeon in 2006, the task has not gotten any easier. Neither has it desensitised him, even though he has to do it a few times a month.

While he grows and gains more life experience, and finds himself more equipped to empathise with his patients, he still does not have an SOP to help patients cope with death.

This is something we are not used to, in a society where templates, guidelines, and rules are de rigueur. Every case is different, he says. Ultimately, he has to consider the patient’s family dynamics and ensure the patient knows what’s going on.

Prof Tan also shares that it helps that more Singaporeans these days are slowly opening up to such die-logues, compared to more than a decade ago when 70 to 80 per cent of families did not want to do so.

That being said, it is still slow progress. Out of love, many keep their loved ones in the dark about their condition. These people believe their loved ones will find that sort of information too heavy a burden to bear.

However, Prof Tan questions if this is the best approach. That is why he is trying his best to persuade family members to discuss the dying process together, rather than shy away or withhold details from their loved ones.

When families exclude their loved ones from the discussion, the decision becomes a huge burden for them. Nobody knows the right or wrong thing to do.

Some do more by prolonging treatment because anything less, such as stopping treatment and letting the patient live out their last days, may be perceived as unfilial. But doing more may not necessarily be in the best interests of the patient.

Prof Tan shares a story with me: He had an elderly Eurasian patient, whom he called Amy, with less than a year left to live. What struck him the most was the control Amy had over her life, even after being diagnosed with cancer. She was with her family and well-prepared to learn about her fate.

“This is my life, this is me. I want to know everything and know how much I have left to live. I will decide from there and not burden my family to do it,” Amy said.

Prof Tan recalls having a good conversation with her over her prognosis and told her that the cancer had spread, with little hope for recovery. Maybe it helped that Amy was a religious person, as she was comfortable with the chat and ready to face death.

Amy took things in her stride and chose not to undergo any further treatment. Instead, she led the final lap of her life meaningfully by travelling and spending more time with her extended family.

Prof Tan remembers that even when she met him after her condition deteriorated, she still maintained a smile on her face. Amy died in October 2019.

“She was able to face death in a positive fashion, so did her family,” Prof Tan says.

Throughout our interview, Prof Tan constantly emphasises that the conversation about death is difficult for anyone to have, be it for dying patients or healthy individuals. Diagnosis should not be withheld, he extols.

But I still had my doubts. Surely it is easy for Prof Tan to persuade us to have such die-logues with our loved ones, when he has a lesser emotional burden. His patients are not blood-related to him, and to them, he is an outsider.

I turned the tables to ask him: Have you had such a conversation with your parents before, asking them about end-of-life issues?

This is when, Prof Tan says, he is no longer a doctor but somebody else’s son. “No matter how experienced a doctor you are, it doesn’t prepare you to be a son.”

Similar to many of us, it was not easy for Prof Tan to bring up the topic with his parents. Certainly not with his mother, who is 84 this year. But thankfully, his late father was open-minded enough to start the ball rolling before being diagnosed with dementia.

He spoke to his son about his final wishes, such as not wanting to be put into intensive care when the situation arose. Prof Tan adds that his father, who eventually died of pneumonia, also wrote him a letter to tell him that he did not want a funeral.

Instead, the elder Tan wanted to be cremated on the same day and have his ashes scattered in the sea, since he loved travelling. The family carried out his wishes when he died.

Like his father, Prof Tan has also written a letter and spoken openly with his daughter on how he wants to be managed in a life-and-death situation. He does not want to be in a vegetative state and burden the family.

Although his daughter is still a teenager, she understands what’s going on. He wants to make things clear to her because life is unpredictable. When push comes to shove, she can at least make an informed decision.

“No matter how experienced a doctor you are, it doesn’t prepare you to be a son.”

This is why this discourse on end-of-life care is so crucial. As recent developments have shown, life is unpredictable. Few of us would have expected the pandemic to last this long, nor anticipated another de facto circuit breaker till June 13.

It is precisely because we cannot foresee the future that we need to kickstart these difficult conversations with our loved ones, especially while everyone is still clear-headed. The last thing we want is to go through a conundrum when our parents are in a comatose state, and unable to express their wishes.

Other than having a die-logue, Prof Tan says, the more important thing is to establish a good relationship with your loved ones, so that when one is at the crossroads, you know that any decision will be made with love.

Do you intend to talk about end-of-life care issues with your loved ones? Tell us about it at community@ricemedia.co.

If you haven’t already, follow RICE on Instagram, Spotify, Facebook, and Telegram. If you have a lead for a story, feedback on our work, or just want to say hi, you can also email us at community@ricemedia.co.