What comes to mind when you hear the word ‘activism’?

Do you think of people speaking up bravely and fighting valiantly against injustice and prejudice? Or do you immediately get the impression of troublemakers and rabble-rousers who can’t seem to mind their own business?

More often than not, Singaporeans seem to perceive the latter.

In July last year, Rachel Yeo, then-NTU student and Research & Advocacy director of the Inter-University LGBT Network (IULN), was uninvited from a TEDx Talk session at St Joseph’s Institution (SJI) a day before the event.

Subsequently, in a speech to the school that was recorded and leaked online, SJI Vice-Principal Leonard Tan said that the reason for rescinding her invitation was because she was “a LGBTQ+ activist”, further stating that “any form of activism is socially divisive”, and went against the school’s principle of community-building.

This inevitably made waves. In some chat groups I was in (which included former Josephians), many were flummoxed and indignant at Tan’s remarks, with some even pointing out, “Wasn’t Jesus an activist himself?”

Yet, in the online sphere, aside from the usual vitriol aimed at LGBTQ+ people, there were numerous comments on how schools were “not the right place” for activism.

Ask Rachel herself though, and she’ll tell you that she never really identified with the term to begin with.

“When I first joined IULN … all I was concerned with was conducting sound research, producing helpful resources, and speaking on panels to raise awareness of the challenges faced by queer students,” says the 24-year-old, who has since graduated and now works in the media industry, and is now Executive Director of IULN.

“The title of ‘activist’ was really only used on me by media outlets and Mr Tan during the SJI fiasco. It carries connotations of militancy and rebellion, which is somewhat unfortunate.”

But she’s quick to add that she’s comfortable with the title: “There’s no shame in that. I’m still same old me doing what I’ve always done.”

Implicit in this whole debate was the notion that activists were needlessly confrontational in challenging authority, perhaps influenced by how some local activists have run afoul of the law in recent times.

In the wake of the SJI hullabaloo, a friend who is now a teacher texted me to express his thoughts on the issue. He opined that while educational institutes at the Junior College level and below should maintain a fine balance between freedom of expression and guided learning, universities were perfect avenues to hold such talks and encourage openness to ideas.

And in some universities, a new slew of student groups are doing just that, actively speaking out and encouraging their fellow students to take a stand on issues close to them.

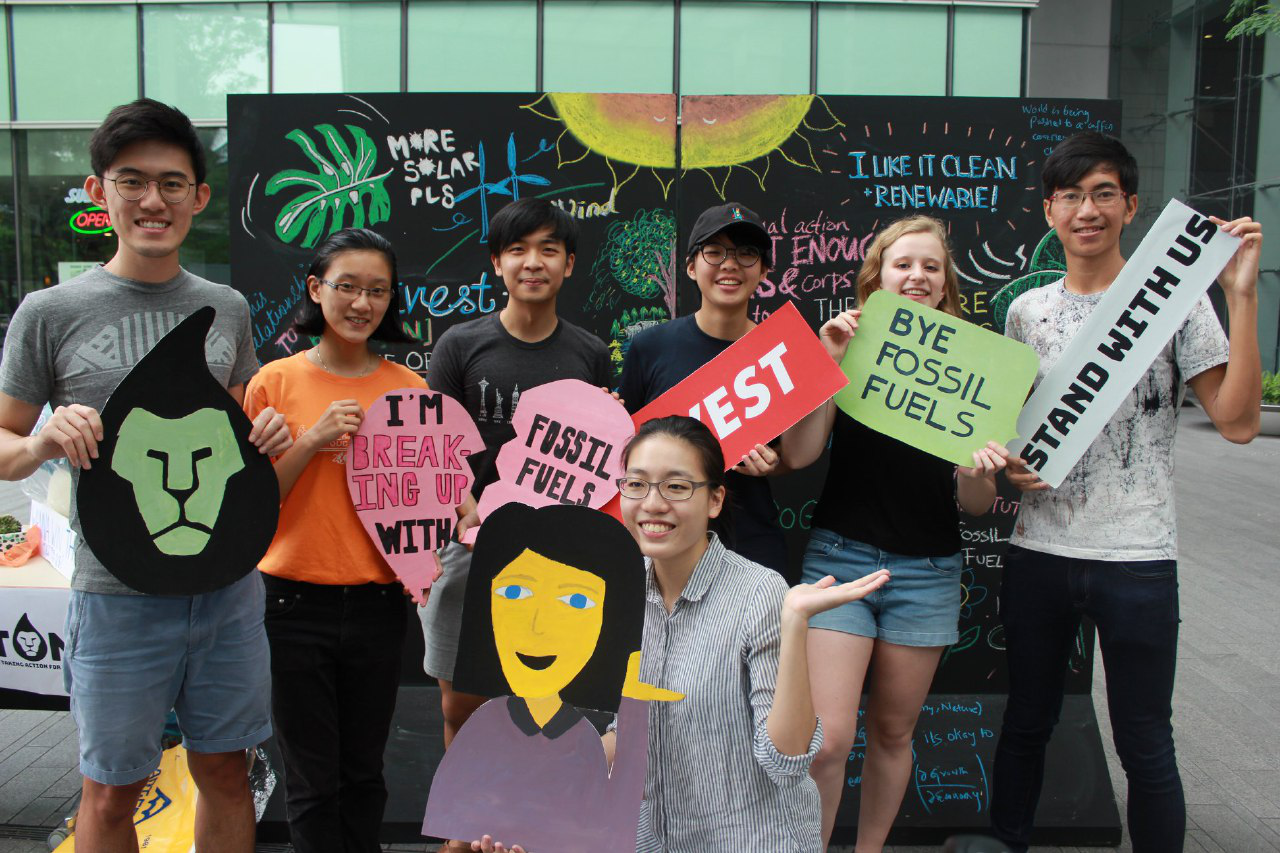

In NUS, two groups have emerged to push for the school to take greater steps to combat climate change, apart from encouraging individual changes to behaviour. Together, Students Taking Action for NUS to Divest (STAND) and Fossil Free Yale-NUS launched a petition in the second half of 2018 to ask NUS to make no further investments in fossil fuel companies, divest all existing investments by 2024, and re-invest those funds into environmentally responsible enterprises.

The petition has since gained over 500 signatures, and they aim to deliver it to the NUS administration sometime in 2019.

In addition to the petition, both groups have been out and about on campus, reaching out to students via booths in residential colleges and at the NUS Climate Roadshow, as well as social media campaigns to encourage students to share their thoughts on climate change. To gain support for their cause, they have also written op-eds that local media has published.

“The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report clearly posits that we cannot address climate change without addressing the fossil fuel industry,” says Jay Wong, a year 2 Environmental Studies major and one of the founders of Fossil Free Yale-NUS.

“This led us to divestment, one of the most effective actions that we can ask our institution to take. After all, sustainability is a core value of NUS.”

In addition to LGBTQ+ and climate change groups, which have more specific goals in mind, other groups have emerged to tackle more explicitly political issues, and to increase civic education amongst students as a whole.

In NTU, the Nanyang Apolitical Society (NAPS) publishes commentaries and thought pieces about Singaporean politics and policies, breaking down complex issues into easy-to-digest chunks for students, encouraging them to get involved.

Ryan Lee, a second-year Public Policy and Global Affairs student and Vice-President of NAPS, tells me that his motivation to form NAPS was simple: he just wanted to gather people who were passionate about politics, and create a space for them to share their views.

“I was tired of the tame level of political discussion amongst Singaporean youths, where almost every idea ultimately had no real conclusion besides vague notions of ‘consensus’ and ‘balancing views’. I wanted a place where all students could pin down their political views without apology, and not remain fence-sitters,” says Ryan.

In addition to national issues, NAPS has also delved into student politics, with the team covering the last NTU Students’ Union elections and calling for greater transparency about the election process. They also publicised rally dates, which they felt were not properly and adequately publicised on official channels.

For Ryan, his main gripe was “how the election was seemingly unnecessary, given that no one really pays attention, goes to rallies or votes”. To him, “both regular students and those running for office saw the elections as a rubber stamp, a mere process to go through.”

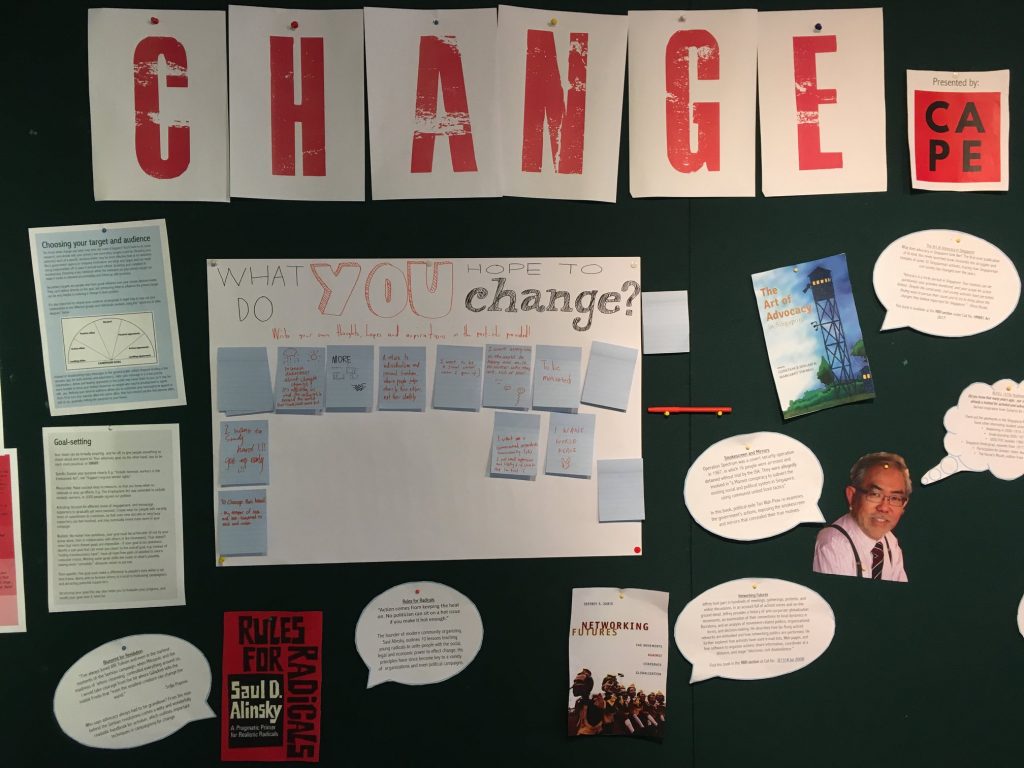

Similar to Ryan, Carol Yuen, 22, was concerned about the lack of discussion of and action on social and political issues in her immediate community, the NUS Law faculty. Together with her friends from Yale-NUS, they formed the Community for Advocacy & Political Education (CAPE) in December 2016 to encourage advocacy and inspire action amongst youth on these issues.

On Facebook, CAPE publishes infographics breaking down political processes in Singapore, such as Meet-The-People Sessions and delivering parliamentary petitions. During the school term, CAPE also sends out a biweekly newsletter called CAPE Curator summarising political news in Singapore. (Disclaimer: I am the coordinator for CAPE Curator.)

They have also organised talks with Members of Parliament like Louis Ng and Leon Perera for students and the general public to learn more about the parliamentary process, as well as a Student Activism Forum, where students learnt about strategies to employ in activism from seasoned activists.

While these groups have enjoyed a certain level of success on campus, I wondered: were they ever cautious about getting in trouble with the authorities? After all, the history of student activism in Singapore suggests that such caution might be prudent.

The first major student protest movement in Singapore (then Malaya) is widely taken to be the 13 May incident in 1954, when nearly 900 students from Chinese middle schools clashed with riot squads over the colonial government’s decision to introduce mandatory conscription. Chinese middle school students would continue to clash with the colonial authorities throughout the 1950s.

Similarly, the University Socialist Club, a left-wing student group in the University of Malaya (now NUS) spoke out against colonial authorities, and eight members were arrested on 28 May 1954 for publishing an allegedly seditious article in their magazine, Fajar. The ‘Fajar Trial’, which only lasted three days, notably featured Lee Kuan Yew as their junior counsel, and he gained the trust of many Club members, paving the way for the establishment of the PAP.

Campus activism continued to be vibrant until the 1970s. Between 1974-75, University of Singapore Student Union (USSU) leaders Tan Wah Piow and Juliet Chin rallied students from all four existing tertiary institutions to protest against the government of the day on issues like the rises in local bus fares and the retrenchment of American Marine workers.

This then sparked a reaction from the government, which arrested Tan on charges of causing a riot in the office of a PAP-affiliated union, while five of his fellow student leaders, including Chin, were detained and deported. The government then amended university constitutions, changing the structure of the Union (students lost the right to elect their own leaders), placing the funds of the Union under the university administration.

These actions, according to historian Mary Turnbull, marked “the end of student activism” in Singapore, and fellow historian Dr Huang Jianli describes these actions as having the effect of “depoliticising the student community and confining students to their studies.”

Dr Kevin Tan, Adjunct Professor in Law at NUS, notes that the events of 1974-75 signalled that there would be a “high price for student activism”, and this has set the tone for the dearth of student activism since then.

Hence, while student activism has flourished in other nearby countries like Indonesia, playing a crucial part in the fall of the Suharto regime in 1998, and also providing the base for climate protests in Australia (which was in turn inspired by 15-year-old Swedish student Greta Thunberg), such activities are notably absent in Singapore, with the shroud of punishment hanging over any potential students who might want to test the system.

Of course, the present group of student activists have employed very different tactics than those in the past. Yet, I asked them: did they ever feel scared that they would be seen as challenging the authorities and would be similarly repressed?

“Personally, no. I don’t think we are challenging most of the time or at least not challenging for the sake of challenging. We are creating a space for discussion and trying to ensure that our views are heard by the authorities – they can’t possibly be hearing only affirmation, which would be unhealthy for Singapore,” says Carol.

Bertrand Seah, 24, one of the founders of STAND, notes that “actions like mass rallies or non-violent protests are fairly common in universities in most countries,” yet the political culture in Singapore makes it such that there is a “chilling effect” that puts people off from pursuing such radical options for fear of repression.

“In any case, we haven’t found the need to be very confrontational in our approach so far … the more practical consideration for us at this point though is that if we tried more confrontational tactics it would probably alienate many of our potential supporters,” he says.

There’s evidence, however, that this “chilling effect” is still present to some extent. Rachel tells me that one of the member groups in the IULN has had to lay low after the debate over the abolishment of Section 377A last year to avoid backlash from their school, but doesn’t specify which one.

Carol also adds that CAPE intentionally frames its work in a “polite and rational” way, and refrains from using sarcasm to avoid being seen as people “out to create trouble”.

“It’s unfortunate that expressing your honest views and beliefs tends to be seen in this way, but we have to work with such a climate,” she says.

However, I press further: has this political climate fostered a sense of apathy in students? And how has this affected their causes?

“Not at all!” Rachel answers enthusiastically, “Students from SIM, SUSS and SIT have approached me for advice on how they can start their own groups. Youths care a lot about solving the problems they see in their environment.”

Ryan, echoing Rachel, says that he doesn’t think students are apathetic: “They might have misconceptions, but that’s expected, especially given how opaque political news can be in Singapore.”

Similarly, Jay states, “More than apathy, what we experienced was disempowerment and uncertainty. We found that people do really care about climate action. But because climate change is an issue so large in scale, people as individuals are unsure about what they can concretely do.”

What exactly separates these student activists from those of the past? It seems, to me at least, that they are using techniques of ‘pragmatic resistance’.

A concept developed by law professor Lynette Chua, ‘pragmatic resistance’ is a strategy used by gay activists in Singapore, where they “adjust their tactics according to changes in formal law and cultural norms, and push the limits of these norms while simultaneously adhering to them.”

In other words, they refrain from confrontational tactics like street protests and avoid being seen as a threat to the state and/or formal arrangements of power.

“Someone has to do something. Why can’t that be you?”

Examples of such tactics would be campaigns publicly calling for legal reform such as the #ReadyforRepeal campaign last year, or Pink Dot, a yearly gathering in Hong Lim Park to promote the diversity of sexuality.

In the case of these student activists, the cultural norm in question is the traditional view of activism as ‘divisive’, which supposedly has no place in institutes of learning.

While protests on campus are illegal, there seems to be no need to resort to such tactics, as these student activists have used ‘pragmatic resistance’ in emphasising the need for popular support when pursuing particularistic goals like climate change, and working with, rather than against, the authorities.

Similarly, on political issues, NAPS and CAPE have framed their activities in an educational rather than confrontational manner, emphasising the need for students to take the lead themselves in advocating for issues they care about.

Thus, rather than being ‘socially divisive’, these groups are reframing student activism in a more inclusive and outcome-focused manner, which perhaps can be a way forward towards reviving the vibrant student activism culture of the past.

Yet, in the process of researching for this article, I could not find similar groups at the JC or Polytechnic level. Was this because the environment was not conducive towards such efforts? What about potential criticism that student activism was only for ‘the elite’ in universities?

Perhaps pre-empting my point, Bertrand states that being a university student “means that you are in a privileged position in society”, as they receive much more opportunities and resources than the average person would.

“To me this confers a great deal of responsibility to make use of that privilege in ways that make the world a better place, or seek to redress whatever injustices might be happening,” he adds.

CAPE has organised workshops for students in Eunoia JC about Singapore’s political system and advocacy methods, and Carol tells me that far from being apathetic, she found the JC students highly interested about such issues.

She also notes that there are many “defined programmes, many community projects and compulsory co-curricular activities that students can be involved in…which would provide platforms for students to think more about social issues and start their own advocacy projects.”

Jay also points out how they are leadership programs like Chili Padi Academy that cater to tertiary students, and proposes that JCs and polytechnics can reach out and collaborate with organisations, whether from universities or outside, to encourage their students to learn more about social engagement and activism in practice.

“Students should be encouraged to act. We must practice as much as we intellectualise theory.”

As someone who has never really been much of an advocate of any particular cause, interviewing these student activists has inspired me. Although these students have had their fair share of frustrations along the way, they constantly emphasised how they were not just questioning for the sake of questioning, but to make impactful change for their future.

I then ask if they have any words to encourage fellow students to their cause, and Rachel’s answer surprises me at first.

“I wouldn’t say it’s important for students to be activists,” she says, before adding, “Rather, I think it’s important for students to always question inequalities and injustice, to use their voice, to find solutions to problems and to just do more than pay lip service when it comes to vulnerable members of our population.”

“You can’t keep saying “This is so sad, hor?” or “I wish I could do something about this” and then just sit on your fingers hoping for someone to do something.”

“Someone has to do something. Why can’t that be you?”