In 2017, I found out my teacher was gay.

Earlier that year, it was announced that foreign participation was banned in Hong Lim Park, and so, in a show of support, I was at Pink Dot for the second time ever.

It was also the second time I was there alone.

In the crowd of unfamiliar pink, I saw a familiar figure, welcoming participants into the park. I was still in NS, and didn’t think I would recognise anyone from school. But there he was, enthusiastic and cheery, the way I remembered him teaching in class. I made my way over; pleasantries were exchanged, and we caught up a little.

During my secondary and junior college years, I had never thought about the sexuality of my teachers. Apart from the occasional, half-hearted speculation, not much thought was given to it amongst my peers.

So what if a teacher was gay? It didn’t affect us at all.

Still, at Pink Dot that day, the question hung in the air between us, aching to be asked. At some point in the conversation, perhaps sensing my curiosity, he answered it, frankly, and without a qualm.

Looking back, I’m thankful that he felt comfortable enough to share an important facet of his life with me. I did, however, feel guilty for not picking up on it earlier, and for my general obliviousness to the lives of my teachers.

I’ve shown up to every Pink Dot since, but it also left a nagging question behind: what’s life like for a queer teacher?

“I would like it if my school were ready to step in and defend any instances of bullying and homophobia, but I really honestly can’t imagine that happening.”

“If you come out, your hopes of being promoted to principal-level are basically dashed.”

These are just some common refrains I’ve heard based on my correspondence with several queer teachers for this article. Acceptance and inclusivity, it seems, remain empty buzzwords within the confines of the school environment.

If you’re still doubtful, let me ask you this, when was the last time you’ve heard of a queer teacher publicly coming out?

If your first thought was Otto Fong, you’re right—and that was 12 years ago.

In September 2007, he came out in a blog post while teaching at Raffles Institution (RI). The blog post went viral, generating an unprecedented furore and dominated national discourse.

Singapore’s answer in 2007, seemed to be this: yes, but strictly as a private individual and never as a teacher in the civil service.

There were plenty of angry phone calls from parents and outsiders baying for Otto’s resignation.

“The Ministry of Education (MOE) said to take down the blog post and apologise,” he says, “I suppose an unapologetic gay man is scary for many people to contemplate.”

Although there were numerous unhappy parents, there was also support. A parent of a student he taught took him out for coffee in a show of solidarity, and many students stood up for him.

“Some students told their classes: “If anyone wants to give Mr Fong grief, he has to answer to us.” The student prefectorial leader went up to me during a flag-raising and shook my hand.”

Looking back on the controversy today, Otto guesses that it was largely because he had voluntarily come out, as opposed to having been caught doing anything nefarious.

“I had a good record for 8 years. It’s easier to call for a teacher’s resignation had he or she broken the law, or was preying on students.”

How infuriating this must have been for an angry homophobic parent.

Despite external pressure, RI was thoroughly supportive of Otto. He was able to continue teaching until he voluntarily left to pursue other career aspirations. This was only possible—I suspect—due to RI’s queer-friendly staffroom, and the school’s ability as an independent school to have final discretion on hiring decisions.

It did not mean that discrimination was absent from the rest of the teaching profession in Singapore:

“I know of teachers and educators who feared for their jobs, and a few were dismissed for weird excuses and had to join the public tuition industry. Some had to give up their applications for education posts when security check personnel sat on their applications, refusing to approve nor reject their applications. This happened to two friends and myself when we applied for NUS positions, but our applications were finally approved when we came out to the relevant parties and asked if it was due to our sexuality.”

Otto adds, “My application was ‘pending’ for 3 months before I approached my then-boss and suggested it was because of my sexuality.”

Outside of Raffles Institution, where schools are under MOE’s direct authority, other queer teachers may not be as lucky as Otto.

“I didn’t experience any direct action on MOE’s part at that point, but later, having left service and wanting to return, I found doors being (politely) closed in my face.”

He also speculates that “MOE seems to operate a blacklist of gay teachers, and policies definitely exist on the hiring, deployment and treatment of LGBTQ teachers, but as with virtually all of civil service policy, it’s hidden behind and protected by the Official Secrets Act.”

“When LGBTQ teachers run afoul of these policies, there’s very little room for redress or even clarity about how they had ‘transgressed’.”

But that was just how Singapore was, circa 2007. Surely things are better now?

One major tell-tale sign of how discrimination against queer teachers persists is the immense chilling effect it continues to have.

I had first-hand experience of this when faced with the almost insurmountable iceberg of getting my interviewees for this story to go on record.

Across the board, whether it was secondary school teachers, junior college subject tutors, or Heads-of-Departments, few queer teachers in Singapore were willing or comfortable with openly discussing their experiences in private conversation, let alone on a media platform.

Even those who had left MOE’s service declined to be named.

A secondary school teacher who was initially willing to share their experience with me eventually backed out reluctantly, citing fear of reprisal from MOE. They had found out that being interviewed about one’s experience as a teacher without MOE’s permission is an offence.

“I know there will be a public backlash, despite the support I will get from some teachers and even students.”

“MOE has been very upfront about its policies and teachers have often been warned of following the ‘code of conduct’, and what we say should not contravene the MOE’s public stance because we are public servants, and since we are teachers, we are held to an even more ‘stringent’ standard from the rest of public service.”

“The school environment, especially at higher levels of authority, is still very conservative. Even if they may privately support, if public pressure is too great, they may be forced to take actions to be answerable to the shrill demands of certain segments of society.”

I would be negatively judged by MOE, no matter how capable I am as a teacher.

Ren*, another teacher in her 30s who simply identifies as queer, agrees that she wouldn’t come out, partly because she prefers to remain private.

“This is none of my students’ nor MOE’s business,” she says, although she does also fear reprisal from MOE—“I would be negatively judged by MOE, no matter how capable I am as a teacher.”

As for John*, coming out remains an unlikely possibility. He’s well aware that it would turn into a “rather heavily politicised event”.

“The moment it’s out there, there’ll be all sorts of narratives ascribed to my identity, narratives that I would not be entirely comfortable with and which I have no control over … parents might think I’m out to corrupt their children. The pro-LGBT side might see me as some martyr figure. My bosses will suddenly think I’m this dangerous individual whose moderately liberal beliefs are now newly recognised as radically subversive perspectives. So on and so forth.”

This lack of control over their personal narratives and the judgement cast from all sides is what queer teachers risk if they come out publicly.

Only Kenneth*, a 34-year-old gay teacher, bucks the trend; he’s the only queer Singaporean teacher I encounter who’s come out publicly. But here’s the caveat: he came out not in Singapore, but Australia.

“I have left the teaching service in MOE permanently because of my inability to be authentic and real with my students. I took it one step further by migrating out of Singapore completely.”

As an international school teacher in Melbourne, Kenneth doesn’t have to hide who he is, and is free to teach without fear. To remove yourself from Singapore may seem like a drastic step, but if queer teachers want to be authentic and real with their students, it may be the only way to do so.

At the same time, surely people must be more accepting of queer educators and queerness in education?

Stella is blunt about this: “What’s the point in even wasting time to think about such issues when the culture of non-acceptance is an open secret with the government ignoring the pink elephant in the room?”

Whether it’s heard, observed, or experienced, it seems that discrimination is the word of the day for queer teachers.

“Sexuality education is meant to teach students that being gay is wrong.”

This is the sort of thing Stella hears her fellow teachers say to students.

Another fellow teacher of Stella’s who voiced support for queer rights and publicly disclosed their membership in a queer NGO, was told to delete ‘objectionable’ social media posts and “warned to distance themselves from anything related to LGBT issues”.

John, another victim of the chilling effect, declined to talk about the discrimination he has faced himself, citing fears of being traced.

But he’s heard of prospective teachers being blocked from joining the service because an interview panellist was “openly homophobic” and refused to pass applicants with “effeminate behaviour”. He’s also heard that being suspected of homosexuality is reason enough for superiors to judge your annual performance negatively.

Ren explains, “If a queer teacher comes out or says something supportive of LGBTQ rights, their job could be at risk. All you need is one conservative student to tell their parent, this one parent complains to the school/MOE etc, and these complaints—even anonymous, unfair, inaccurate ones—could really get a teacher in trouble, harassed by school authorities, and/or blacklisted for future teaching positions.”

“MOE doesn’t even need to get the teacher’s side of the story.”

Unfortunately, my attempt to reach MOE for clarification on their policy stance towards queer teachers was met with silence.

While the queer teachers I spoke to are all unaware of any official guideline or policy that MOE has, they’ve all heard of incidents and rumours: from being left to hentak kaki without promotion to Dominic’s speculation of a ‘blacklist of gay teachers’.

In the absence of an official policy stance, some queer teachers like Stella and Ren take their cue from how 377A is incorporated into Singapore’s education curriculum.

“What do you think? When sexuality education still teaches that homosexuality is illegal because of 377A? What sort of message does it send to teachers?”

“Homosexuality is cited during the sexuality education programme only in terms of “current legal provisions concerning homosexual acts in Singapore”, as a legal deterrence. So 377A is enforced—through education!”

Others, like John, feel that a non-policy is a policy unto itself with obvious implications.

As John muses, “If there is an actual set of rules/policies/directives, then there are protocols to be followed, cases to be investigated, and rules to be consulted. In the absence of such rules being set in stone, what we end up with is a carte blanche of sorts, where the powers-that-be get to make all sorts of arbitrary decisions without needing to consult some official document. This also means that the capacity for discrimination and abuse is there. When you have an entire demographic rendered invisible in your policies, so too would the methods be for dealing with issues pertaining to queer teachers. If there’s no directive in place to consult when a homosexual teacher is accused of sexual harassment by a fellow colleague, then you get complete powers to decide. That is, I think, a very frightening thought to entertain.”

“If there isn’t the slightest mention of LGBTs in guidelines/policy/directives, then the message to you is pretty clear-cut: stay invisible.”

The ambiguous absence of official policy clarification also creates a grey area in education as to how queerness should be handled in a school setting. Just look at how Singapore Polytechnic (SP) removed Joshua Simon from it’s TED Talks’ speaker list. According to Joshua Simon’s account, a representative of SP admitted to him that the action was taken to abide by MOE’s ‘rules’. Just days later, however, SP came out to dispute this version of events; Joshua Simon’s statement was reframed as an allegation, and responsibility for what had happened was shifted onto the student organising committee.

The fact is that all of the teachers I spoke to remain unaware of any official MOE-mandated ‘rules’ governing queerness in school settings. What it might have really been was SP practising self-censorship to toe the pink 377A line, and then regretting the action taken after coming under fire for it.

This is the statement Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong makes in 2019, just days before Pink Dot 2019 took place in the democratic sanctuary of Hong Lim Park.

If you’ve been keeping up till this point, you’d know that queer teachers would (if they could) tell you, that remark is a real-life falsehood; feeling ‘‘welcome to work in Singapore’ is not a guarantee for all.

Maintaining that we have ‘welcoming’ policies may work for courting foreign investor-friends to our little island, but it does little for our queer citizens when 377A continues to affect domestic socio-cultural attitudes with its trickle-down effects on their everyday lives.

As it is, younger generations of Singaporeans have generally been more accepting and inclusive. Indeed, the queer teachers I spoke to generally agreed that their students were likely to have a neutral or positive response if they were to come out to them.

The issue preventing queer-affirming policies in schools is then perhaps that of hostile parental attitudes. If parents kick up a fuss and throw tantrums, there’s probably little schools can do but accede to their demands.

But what explains the parental prejudice against queer teachers?

I reckon it’s the combination of ugly queer stereotypes and the status of teachers as authority figures. For some, queer people are seen as immoral beings, ‘obsessed with sex’ and always looking to ‘convert’ innocent bystanders into one of their own. When parents who hold this misguided view find out a queer person is a figure of authority, ignorance, paranoia, and a misguided sense of morality can manifest in apparitions of vile sexual predators defiling their children.

Angry phone calls are made. Voices are raised. And somewhere out there, a teacher is quietly transferred out of the school.

In fact, the strong association between men and sex in Singapore, coupled together with unsavoury mainstream media representations of gay men may generate more stigma towards gay male teachers than female lesbian teachers.

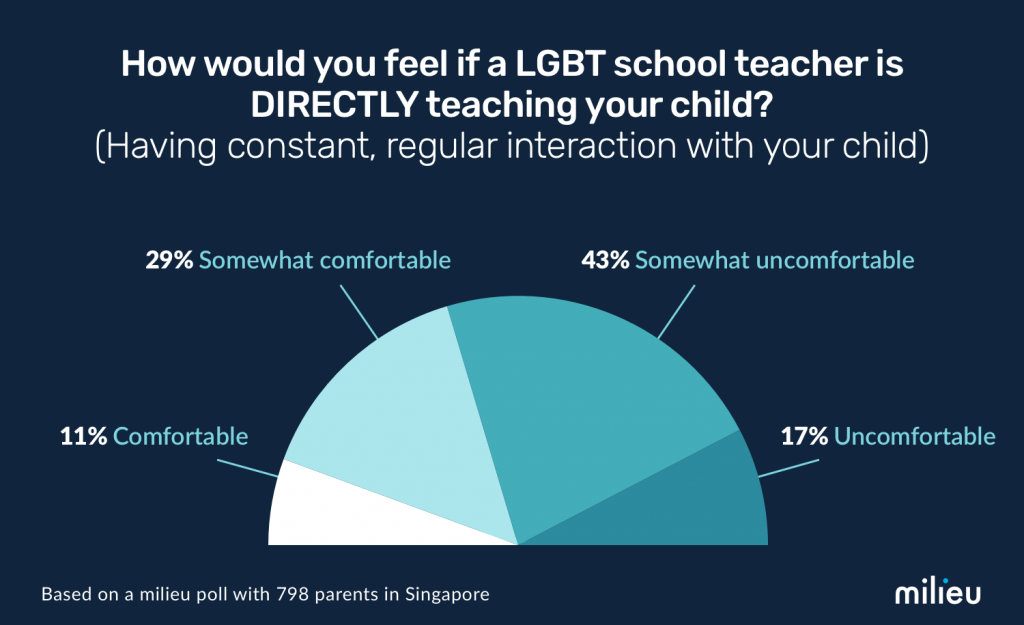

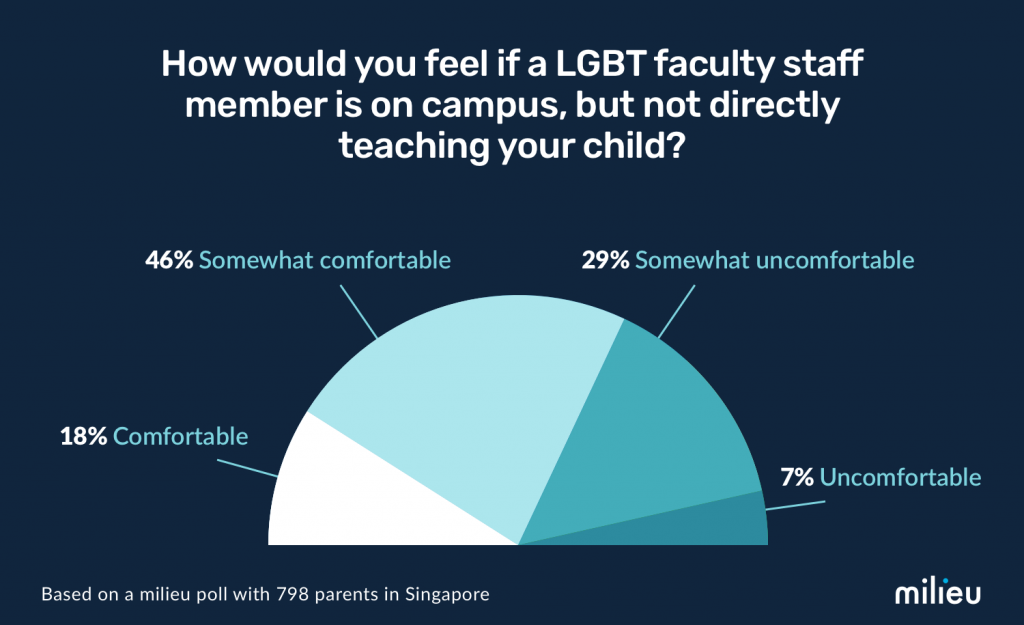

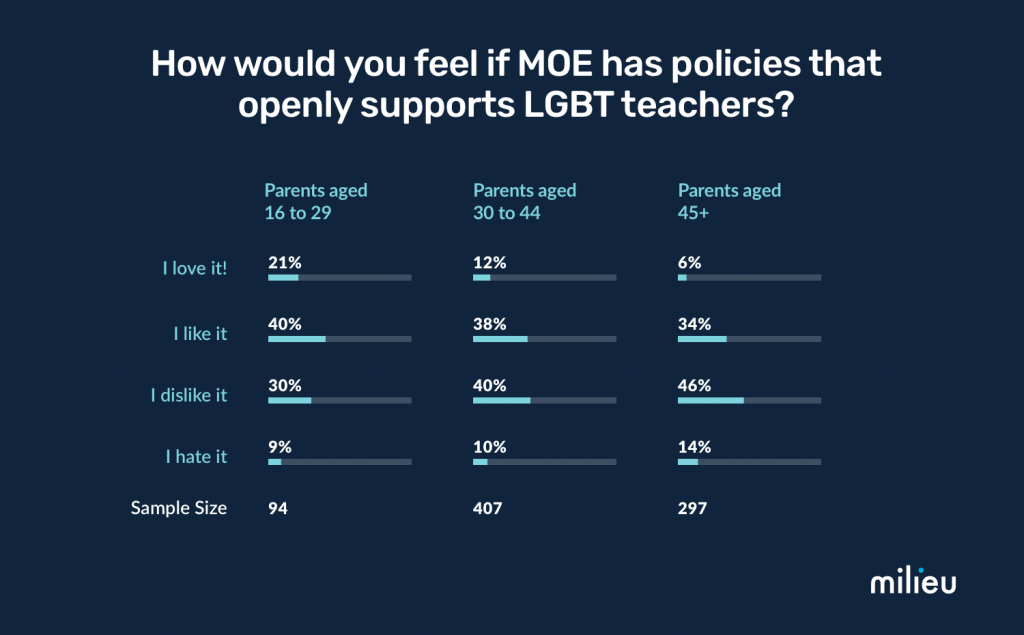

Of 798 parents with school-going children in Singapore, a 60% majority of parents still expressed discomfort at the thought of having a queer teacher having constant, regular interaction with their child.

At first glance, the survey results seem bleak about the current possibility of queer teachers being open with their sexuality. But the same survey also suggests that winds of change are coming.

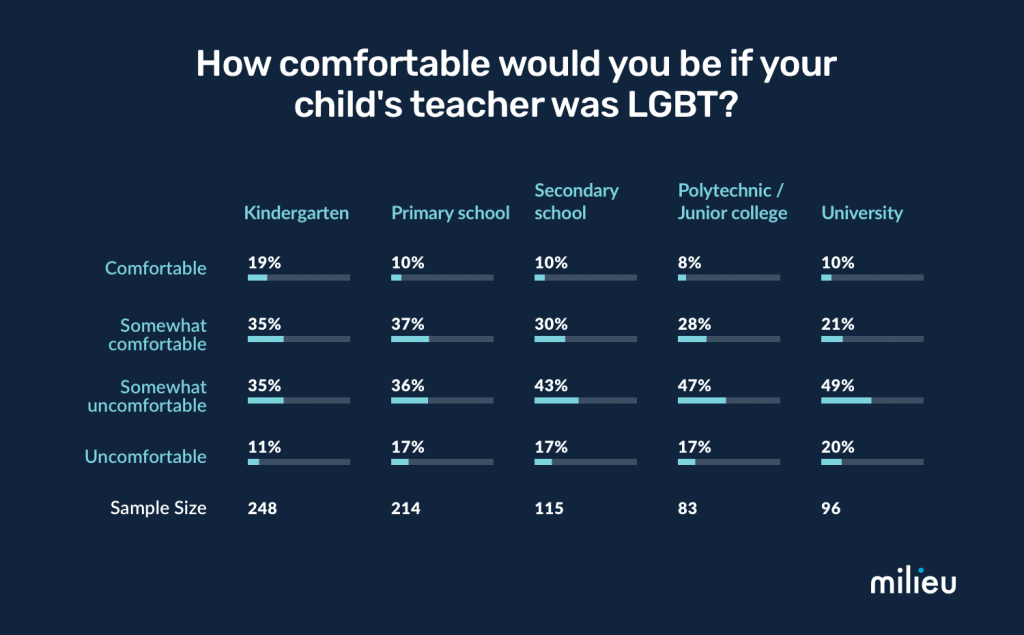

One common false argument against queer teachers is that homophobic parents are afraid they will ‘influence’ children with their queerness, and ‘turn them gay’. By the same logic, the younger your children are, the stronger your fear should be.

Parents of kindergarten kids should be quaking in distress at the thought of finding out their child’s teacher was queer. Parents of university students, on the other hand, should be more relaxed about realising their child’s eccentric professor is queer.

756 parents surveyed were unaware if their child had a queer teacher. Of these parents, 64% of those with children enrolled in kindergarten, are comfortable with their child having a queer teacher—higher than any other group of parents.

In stark contrast, only 31% of parents with children enrolled in university felt comfortable with their child having a queer teacher.

This anomaly can be explained by the fact that current parents of kindergarten-age children are themselves younger than current parents of university-aged children. These younger parents might possibly have more accepting attitudes towards queer issues and people.

In other words, young people are spearheading change for the better, yet again.

As it stands, 48% of all parents surveyed would approve of MOE having policies that openly support queer teachers. That’s almost half of all parents.

I’m not sure how far away we are from 377A being repealed, but in the interim, I have to agree with her as well, that an explicit statement against unfair dismissal, blacklisting, glass ceilings, and queerphobia—perhaps like the 2003 statement then-PM Goh Chok Tong made in support of hiring gay civil servants—would go a long way in assuring queer teachers that they are valued in society, just like anyone else.

The queer teachers I spoke to for this article, and those who have taught me, all embody the nobility of the teaching profession. All of them were concerned more about the students under their charge than about themselves. All of them were reluctant to leave the teaching service, despite the discrimination they endured.

If you can’t get over their queerness, I leave some of Stella’s words here with you:

“Your child’s teacher is still the same as before you knew that they were queer.”

“Trust us to teach your child the right values and skills so that they can grow up with a critical and open mind to deal with a diverse world.”

The question we must ask in 2019 no longer revolves around whether it’s ‘appropriate’ for a teacher to be queer, but rather, how we can recognise them in their entirety as both a teacher and a person.

Yes, they’re queer.

Yes, they’re just here to teach.

Being queer in Singapore is still a dangerous reality for many. If you need counselling, Oogachaga’s Hotline & Whatsapp counselling services are available to queer individuals in Singapore.

Hotline: 6226 2002

Whatsapp: 8592 0609

These services are available on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays, from 7 pm to 10 pm, and on Saturdays, from 2 pm to 5 pm.

How do you feel about queer teachers in schools? Tell us at community@ricemedia.co.