During the 17th century, the act of smiling itself was thought to be inappropriate. This explains why we rarely see smiling portraits of the aristocrats from that period; smiling was seen as lewd and unseemly, something only those from the lower classes did. Aristocrats preferred to adopt solemn, courtly gazes, in line with the sombre atmosphere of the courts.

The social mapping of impropriety to smiling can be explained by a simple, biological fact: most people had decayed or decaying teeth by their forties, and open-mouthed smiles risked revealing the unattractive sights and smells of tooth decay, gum disease, and bad breath.

The dental revolution in the 17th century, however, ameliorated some of these risks, and led to what historian Colin Jones called “a smile revolution” in 18th century Paris. The dental revolution changed long-standing social attitudes towards smiling, and coincided with increasing optimism and public displays of gaiety on the eve of the French Revolution.

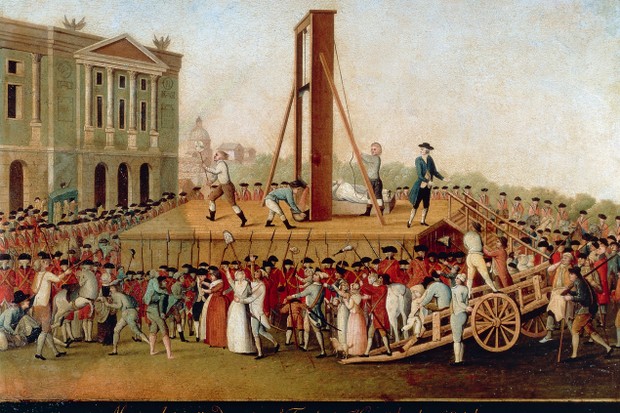

Yet, Jones traces how the Reign of Terror quickly wiped the smile off people’s faces, and how the smile became a suspicious symbol of protest.

While smiles in the early days of the revolution had once been about openness and transparency, and was thought to be progressive and egalitarian, smiles quickly became suspect, in part because the scaffold smile was becoming an emblem of political resistance.

The scaffold smile refers to political prisoners’ deliberate act of smiling before imminent execution, a gesture that unnerved both executioners and bystanders. Considering how public executions were a form of mass spectacle or public theatre, we can consider the scaffold smiles the equivalent of the biggest “Fuck You” prisoners could give to the regime.

To this end, scholar James Scott defined the expression of smiling as “a hidden transcript by which the powerless symbolically critiqued and cocked a snook at the powerful.”

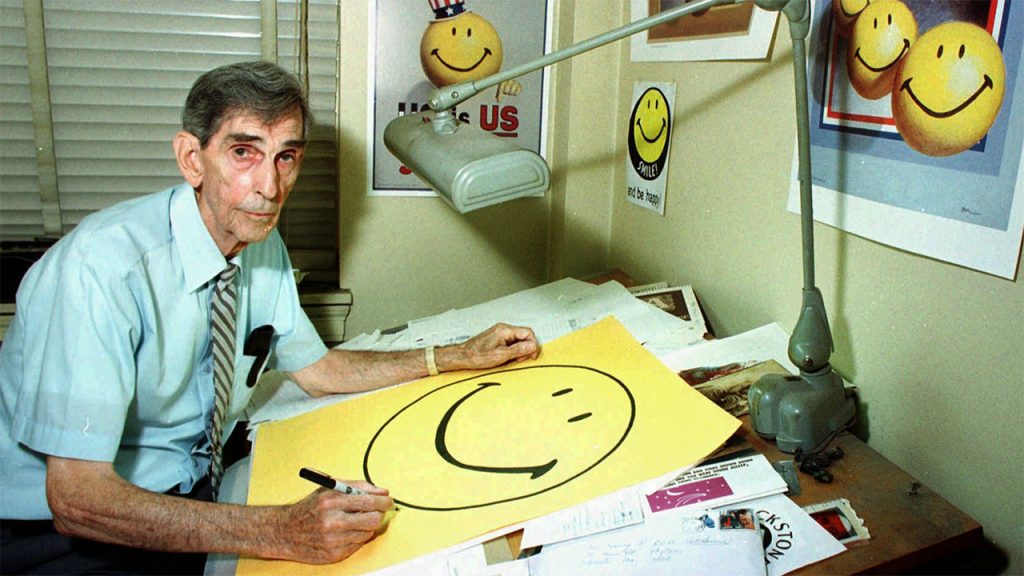

A brief (corporate) history of the modern smiley face suggests that it was first conceived in 1963 by an American graphic artist Harvey Ball, who was commissioned by an insurance company to design a smile that could be used on promotional material to raise employee morale. Legend goes that Ball designed the Worcester smiley in ten minutes, and was paid $45 for his design.

The smiley face transformed from a symbol of American corporatism to counter-cultural icon in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when it was appropriated and subverted by the acid house scene and other musical subgenres like punk rock.

Acid house posters prominently featuring smiley faces proliferated in the 1980s, and the smiley came to be seen as an icon of youthful rebellion, associated with rave culture, ecstasy overdoses, and psychedelic culture during the Second Summer of Love.

Beyond the smiley, the specific use of smiles as a form of political critique in art is also seen in the work of Yue Minjun, a Chinese contemporary artist.

Said Yue, “A smile doesn’t necessarily mean happiness; it could be something else.”

The inherent ambiguities behind a smile means a single smiley can encapsulate several layers of meaning, and its adaptability makes it a useful term in circumventing oppressive laws. In China, netizens have developed elaborate codes and cultures around evading censorship on social media platforms, for instance by using the seemingly innocuous smiley face to signal contempt.

In light of these histories, perhaps the choice of the smiley icon in Jolovan’s placard is one that is not simply endearing but also strategic and loaded with meaning.

My own editor speculated, “Aiyah, maybe he use smiley just cos cute leh?”

(Thankfully), Jolovan swiftly debunked that.

When asked why he picked a smiley face, Jolovan said, “It was a suggestion from a friend and then I thought about what it would mean for me and decided that it would be a disarming gesture. In Singapore, activists are often portrayed as confrontational, aggressive and combative. What i’m saying here is that there’s nothing wrong with speaking truth to power, and we are motivated by peace, love and compassion.”

The smiley face might draw comparison to the floral motifs of the Flower Power movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s, which became symbols of passive resistance and nonviolent protest. Then, activists opposing the Vietnam War utilised methods such as offering masses of flowers to policemen, politicians, and the press.

As one contributor wrote in a photo album compiled by Jolovan, Smile in Solidarity, “Smile is subversive. It is dramatic. It tickles, enchants, disarms the ruthless and frigid hearts of those in power.” The ambiguities behind a smile makes it incredibly fluid and prime for subversion, appropriation, and creative dissent.

In Singapore, we already see signs that the smiley is being commodified and reproduced in creative forms. Local rapper Subhas, together with Rocky Howe, Deesha Menon, and Jean Hew, have launched a campaign to sell smiley tees (proceeds will be distributed to HOME and wares on the mutual aid list). Similar to the edgy “Not a Public Assembly” t-shirt, the smiley tee shows how fashion choices can be used to signal citizen’s political beliefs and test legal boundaries.

In the face of stifling laws such as the Public Order Act, smiling can feel wholly disingenuous.

Yet, absent more fundamental changes to our political system, perhaps the best thing sympathetic parties can do in the near term is to keep smiling. Human rights organizations such as MARUAH have also launched an appeal for smiley images from Singaporeans, to be added to Jolovan’s solidarity smile photo album. For as Jolovan, his supporters, and the various figures in history have shown us, smiling can be one of the greatest acts of dissent. ☺