This is the first in a two-part series about the Progressive Wage Model and the security industry.

Tai Seng is not a place you want to be in at 7:30PM on a Monday night. The area is a Dante’s Inferno by way of Brutalism, a maze of grey-and-yellow industrial buildings designed to make you want to flee ASAP. It’s past dinnertime, and the last office workers are scurrying towards the MRT, already mentally checked out for the day.

Vicky and his colleague, however, aren’t going anywhere. They’re security guards, in the midst of one of the 12-hour shifts they do, six days a week.

“That’s standard for full-time, lah,” said Vicky, 30, of his hours. His colleague keeps an eye on the temperature scanner as we speak, nodding at residents on their way out.

As a Senior Security Officer, Vicky’s basic pay is S$1,400, rising to S$2,500 with overtime. After deducting CPF, that leaves a take-home pay of S$2,000 to support himself and his two young daughters as a single father. This is more than S$2,000 under the median gross monthly income of S$4,563.

“Isn’t that tough?” I asked.

He shifted and adjusted his face mask, pulling it higher over his nose.

“To tell you the truth, ma’am, it is.”

With inequality in the spotlight, the PWM-vs-Minimum Wage debate has generated interest—not to mention debate—in a way policy issues rarely do. Just this week, it was announced that a tripartite workgroup will be formed to explore improvements to the well-being of low-wage workers, including by refining the PWM. But so far, much of the discussion has seemed distant, almost academic, like rehashing arguments for a GP essay: Minimum wage is better because it’s easier to implement and would apply across the board. PWM is better because it increases productivity, not just wages.

It’s one thing to evaluate policies’ effects on the labour market or the cost of services, and another to ask how they actually affect people’s lives. Social policy, after all, is never just about theory; lived experience is its start and end. The more I read, the more I wanted to know: what do workers under the PWM—the real experts, in a sense, of how it works in practice—think of the scheme?

Two themes emerged. One, security guards’ opinions about the PWM had to be considered alongside their opinions about the industry. Two, if they were lukewarm about the former, most were positively unenthusiastic about the latter.

I interviewed five security guards over two days. All were glad to be making an honest living. They were also brutally honest about the downsides of the job.

First, the hours are long. A standard shift, including overtime, is 12 hours, six days a week. The work, while not especially stressful, is physically taxing, and the salary is dismal enough that many officers take on extra jobs where they can (more on that later). It’s poorly paid and poorly regarded, which came through in my interviewees’ comments: the number-one response I got to How do you feel about the job? was a wry chuckle of You think what?

Raja*, a longtime security guard who works in the CBD, told me how he’d warned his son not to follow in his footsteps. “I also ask you, you want this job?” he demanded, jabbing a finger at the Classifieds section of his newspaper. Ads for security roles leapt out from the page. Re-imagine your career with us! chirped one headline.

In this, all my interviewees told me they joined the industry because they felt their options were limited—a decision born of necessity, rather than want.

Kamsani, 55, became a security guard twenty years ago because his qualifications “are not that high”. Ng, 31, who joined this year, did so because he was “running out of options” with only ‘O’ Levels to go on. In our lean, degree-worshipping labour market, the security sector has one key thing going for it: it doesn’t care about grades.

Security Skills 101

The PWM’s main selling point has been that it raises productivity as well as wages. Under its training requirements, employees must take modules under the Workforce Skills Qualification (WSQ) to, well, progress.

Most of the courses are vocational, covering skills like fire safety, operating screening machines, and crowd control. Half my interviewees found them useful, while others felt technical knowledge could only go so far in a role that was—surprisingly—often about customer service: dealing with irate drivers who got their wheels clamped, giving people directions, and so on.

Ng, the junior officer, compared it to NS. “Like army, they tell you do this do that. But by right, when you work, it depends on the situation what. Must see what happens.”

At first blush, the payoff from skills-training seems mostly for agencies. Talk of ‘output’ and ‘efficiency’, after all, means very little to your rank-and-file security guard. But for employees, what the PWM—as an advancement framework which values skills and experience over paper qualifications—offers isn’t just better pay. It’s the chance to access this.

Mohammad*, 41, put it neatly. “The WSQ framework caters more to people like me, who lose out on the academic part,” he told me. Previously, having only ‘N’ levels would have made it it difficult for him to be considered for promotions. “Back then, there’s not much choice unless you took a diploma in security, that kind of thing. It’s like you must jump to the next step. But now it’s like a ladder.”

Nonetheless, whether these prospects exist is a separate question from how many officers actually take them up.

Although it is compulsory for security agencies to adopt the PWM, the upskilling requirements are flexible. Going from an entry-level Security Officer (PWM Level 1) to a Senior Security Officer (Level 2), for example, needs only a year’s experience and two modules. But if you were so inclined, you could top-up to a WSQ Certificate in Security Operations along the way, which requires six modules and 5.5 days to a week to complete.

Of my interviewees, only Mohammad had opted to do this. As a Senior Security Supervisor (PWM Level 4), he was also the only officer I spoke to in a senior or supervisory role. Everyone else was a junior or mid-level officer, some despite having spent decades on the job.

The issue of uptake has a deeper question afoot: after a certain stage, how much upward mobility does the industry actually offer?

Kamsani, the 55-year-old, told me his PWM courses were ‘useful’. But when I probed further—did he mean soft skills? Using technology? What exactly did he learn?—he looked confused. “This job doesn’t need technology,” he said, nodding at his shabby guard post. The setup looked about as old as he was.

I was a little sceptical. For years now, the security industry has been grappling with how to become more hi-tech without automating away half its workforce. All the same, the God of Efficiency hasn’t forced many security guards to hang up their boots yet; if anything, the sector is facing a severe manpower crunch. There are many more jobs than there are people willing to take them.

The catch, according to my interviewees, is that most of these vacancies are for junior roles. If so, any advancement prospects the PWM offers in theory would be limited by early-onset diminishing returns in practice. What incentive is there to upskill if you’d end up overqualified for your current job, but there’s no space further up the ladder?

Moreover, would a security guard in their late 50s, already working 12 hours a day, be motivated to keep optimising into their sunset years? Should they be expected to?

In any case, Raja thought my question was moot. According to him, undercutting is so common that most agencies don’t pay more than the minimum.

He told me about trying to negotiate a better salary after completing his PWM modules.

“After I finish the course I ask them, can claim higher salary or not. They say ask your company. So I ask my company and they say wait and see the client’s quotation. How much going round and round you want?”

“So I wait. Then the quotation comes and my company says cannot pay more because of market costs. Everyone is competing, all the agencies giving lower prices. If you want business, how to go higher?”

How much is enough?

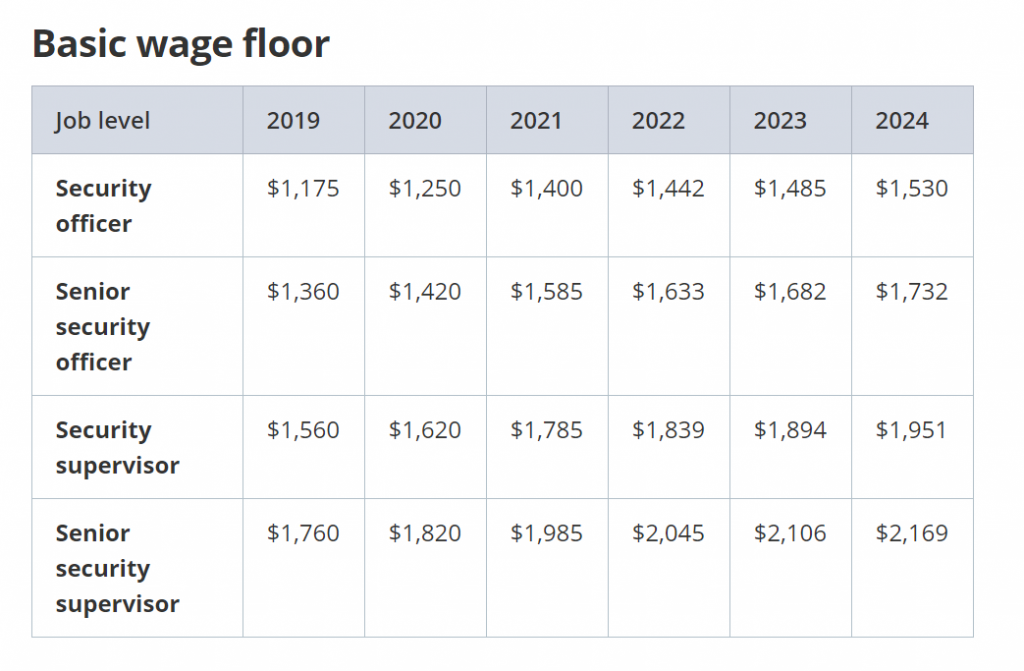

The PWM operates like a de facto minimum wage, thanks to its stipulated salary floors. During his face-off with Dr. Jamus Lim in Parliament in early September, Senior Minister and Coordinating Minister for Social Policies Tharman Shanmugaratnam referred to the scheme as a ‘minimum wage plus’. Between 2019 to 2024, security guards’ pay is slated to increase by around $400 per tier, spread out over the five years.

All my interviewees acknowledged that the PWM had raised their wages. They were, however, divided over whether this had been enough.

How much you need obviously depends on your circumstances—in particular, whether you’re supporting dependents. Both Kamsani and Ng, who are single and earn around S$2,000 after CPF, felt their pay was enough for themselves. (Ng pointed out that working 12 hours a day doesn’t leave much time for going out.)

Nonetheless, his basic hourly rate—after factoring in the PWM increases—clocks in at the princely sum of S$6.50.

“With OT, it’s enough to make ends meet,” he said. “I feel it’s reasonable, but still underpaid.” (Notably, the PWM applies only to basic pay, not overtime allowances.)

Mohammad, the Senior Security Supervisor, saw his gross pay grow from S$2,100 to S$3,300 (before CPF) over his 9 years in the industry. He attributed this to proactively taking courses and upskilling; if he hadn’t, he would probably still be in a junior role, earning around S$800 to S$1,000 less. “That’s a huge difference to me,” he said.

Moreover, he crunched the numbers, and found that for an 8-hour shift (ie. excluding overtime), he makes around S$2,300 a month before CPF—on par with some diploma-level office jobs. Rationalised this way, he thought his pay was fair.

Whether you agree with him is too complicated to answer easily. A 60% pay raise sounds decent; spread out over ten years, it looks much less generous, especially given the rising cost of living. Core inflation has remained fairly modest for the last decade, but prices of certain key goods and services—especially food and healthcare—have gone up. And picking apart the relationship between how much a job pays with how much value it brings, and how commensurate this is with skill level, could fill an entire PhD thesis.

As for whether his pay is adequate, it’s absolutely clear that being a single adult, without more mouths to feed, makes a big difference.

Although Singapore lacks an official poverty line, in 2018, Dr. Irene Ng and a team of researchers at NUS’ Social Service Research Centre estimated the threshold for absolute poverty at S$1,878 for a four-person household. (This is roughly on par with the S$1,900 household income ceiling for short-to-medium-term Comcare social assistance.)

However, Dr. Ng caveated that the estimate was “extremely conservative”, configured for “the most basic of needs”. Families with young children or any chronic health conditions, for example, would need significantly more. Meanwhile, research into a Minimum Income Standard, which adopts a more expansive definition of ‘basic needs’—looking at the minimum needed to enable quality of life, beyond subsistence-level survival—found that a single person aged 55-64 would need $1,721 a month.

Part of the rationale behind the PWM was that pay raises for essential workers were overdue to begin with. But even now, many security guards, particularly those supporting families, are barely staying afloat.

Between 2020 to 2021, basic monthly pay for an entry-level security officer will be raised from S$1,420 to S$1,585. At this level, an extra S$165—an 11.6% increase—is not insignificant. But in absolute terms, you could also see this as going from peanuts to peanuts-plus.

Vicky and Raja, both of whom have raised or are raising children on an average security guard’s pay, are just scraping by. While not in absolute poverty, they are almost certainly experiencing relative poverty: exclusion from the activities and opportunities that the average person might enjoy, and the security, independence, and sense of belonging which these bring.

Raja, whose daughter is now working and whose son is in university, struggled to make ends meet when his children were growing up. Although his wife was also working as a part-time cashier, his starting salary when he joined the industry in the 1980s was only S$800.

“Was it hard? Of course lah!” he said. “Now, starting pay is S$1,600. More than last time. But like that still how to pay PUB, how to buy a house? Last time when I buy my flat it was around S$140,000. Now maybe S$200,000. How like that?”

Vicky, a single father supporting two young daughters, admitted that things were “very difficult.”

“I work 26 days a month, my pay is around S$2,500. But after you minus CPF, even less,” he said. (He does not meet several of the eligibility criteria for Workfare, a social assistance scheme which provides additional wage support)

His daughters receive financial assistance from their school, but as he works odd hours and occasional nights, he has to pay a carer to look after them when his parents are unable to babysit — a necessary expense, but one he is stretched to afford. (His story also makes me wonder how many security guards are their family’s sole or main breadwinner. After all, if one parent is working 12 hours a day, but still doesn’t make enough to afford daycare or domestic help, someone has to look after the kids.)

To supplement his pay, he sometimes takes on extra shifts or ad-hoc work, which he finds through word-of-mouth. Shifts during holiday periods, like Deepavali or Hari Raya, can pay up to S$700 for five days’ work.

“When we are preoccupied by poverty,” write Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir, authors of Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much, “we have less mind to give to the rest of life.” Their research found that the stress of living with poverty, dubbed the ‘bandwidth tax’, can impair decision-making ability.

The S$150 pay raise Vicky stands to receive next year could buy a few crucial things, like food, transport, or a paid water bill. Then there are the intangibles: a few hours’ rest, more time with his daughters, money saved on babysitting, more headspace. But even with that, the struggle is real.

I asked if he plans to stay in the industry long-term.

“To tell you the truth ma’am, probably not,” he said. “If I can find a better paying job, I will leave.”

And where does this leave us? Based on the officers I spoke to, the overall picture looks something like this: greying officers like Raja and Kamsani had been in the industry for over 20 years, but were still in relatively junior roles. Both have enjoyed some wage growth under the PWM, but have little incentive to level up.

Meanwhile, younger officers like Vicky and Ng see more opportunities than there used to be, but are nonetheless holding out for greener pastures.

“Do I want to stay? See how it goes,” said Ng. He, like Vicky, hopes to find better-paid work if he can.

“If pay goes up by 2024, maybe. But I’m still young, so if I can progress elsewhere … I’m going to take a diploma, try something else, if it doesn’t work out I’ll come back to security. This is a backup plan.” Even Mohammad, the senior supervisor, told me his dream is to open his own business someday.

I didn’t read this as a damning indictment of the PWM; far from it. Sentiment was mostly tepid, sometimes positive, but no-one had anything bad to say about it on the whole.

In fact, most of the issues my interviewees raised weren’t about the PWM. They had to do with the security industry itself, and more broadly, how we still undervalue blue-collar work—in all senses of the word.

Covid-19 has prompted soul-searching about many things: which jobs we disdain and which ones we dignify, the gaps in our social safety nets, and the place of compassion in our social policies. The PWM, of course, predates all this; when it was announced in 2014, it was heralded as a timely move to support some of Singapore’s most chronically underpaid workers.

All the same, an extra S$400 over five years both looks like too little and takes too long. Has progress been made? Yes. But progress, to borrow the phrase from Gunter Grass, is a snail.

Or, as one interviewee put it, “The increment is so gradual that I feel no one actually notices the difference.”

The PWM and a minimum wage have several differences in practice and principle. These should be carefully considered, and any policy which aims to support the working poor is worth exploring. But after a certain point, both look like software patches on broader, system-level issues.

The basic PWM salary for a mid-level Senior Security Officer in 2024—$1,732—is still under the absolute poverty threshold today. And if we think of this in a more expansive sense, where ‘liveable’ means more than ‘living close to the bone’, the shortfall looks even greater.

To be sure, addressing these gaps will take more than wage policy. The security industry itself will have to review how it competes for tenders: a market plagued by endemic low-balling will struggle to be truly progressive. Related policies, like social assistance schemes, will need to be strengthened. And the bigger problem of judging jobs—and the people who do them—by how much pay they command, rather than the value they bring, requires a different fix altogether.

“Many people … I’m sorry to say, but they have this mentality that if you are doing accounts, HR, that’s a good career path. But jobs like mechanics, it’s still a skill, you know? Even if you’re a CEO and your car breaks down, you need a mechanic to do the job,” said Mohammad.

“So we cannot … we cannot run away from the fact that the public mentality still thinks engineer, doctor, scientist, are ‘good’ jobs. It’s how we’ve been brought up to see things. But in reality, I call it double-standards, lah.”