Top image credit: u/bolusk1 on Reddit r/Singapore

Schools reopened last week after one month of home-based learning and another month of school holidays. Yet for me as a JC student, the experience has not been a complete return to the way things used to be before the circuit breaker.

In an electrical circuit breaker, the disruption in the flow of electricity is like hitting a pause button. Once you break the circuit, current stops flowing, and the components of your circuit stay the way they are until you connect them back together again. But in truth, a circuit breaker might be too simplistic an analogy for our two-month absence from school. For better or for worse, the school environment has not remained trapped in stasis during our time away.

Over the next four weeks, the JC 1 and JC 2 cohorts of my junior college will be attending school on alternate weeks to limit the number of people on campus. Walking through the considerably emptier corridors on my first day back, struggling to breathe through my government-issued 3-ply face mask, I was hit by a wave of nausea—fuelled just as much by the unfamiliarity of these familiar surroundings as it was by the disgusting odour of my own warm, moist breath being reflected back into my nostrils, accompanied by a trace of Dettol.

“The mask is preventing me from thinking.”

Wearing a mask continuously throughout the school day has been, well, uncomfortable. I often find myself out of breath after climbing a flight of stairs, or power-walking across campus to get to class. Most of my peers have elected to use disposable surgical masks because they are more breathable than the reusable fabric ones from the CC, myself included after my terrible experience with the fabric mask on the first day.

Other reusable masks, such as the first generation government-issued mask which didn’t have the metal nose bridge present another set of problems.

“It keeps slipping,” my Econs teacher apologised while re-adjusting her reusable mask for the third time in the same lesson. Her voice was muffled through the additional layer of fabric. Several times, we had had to ask her to repeat herself—or she, us, when posing our questions to her.

Many of my friends have expressed dismay at the thought that we might have to wear masks while sitting for the A levels at the end of the year.

“The mask is preventing me from thinking,” claimed one friend. “How can I do my exams in this?”

Even the excitement of speaking to and interacting with friends and students in person—something many of my peers and teachers had been looking forward to—has been somewhat dampened by the masks. Holding a conversation with someone is a struggle when you cannot read their expressions, or in extreme cases, hear them. One of my teachers seems to have overcome this with exaggerated eyebrow wiggles and cartoonish ‘angry stares’. But for the rest of us, the verbal response of “I’m laughing under the mask” whenever a joke is told has quickly become a substitute for genuine smiles and laughter.

The only time we are allowed to shed our masks and revel in the freedom of respiration is during our meals and while engaging in physical activity.

“My mouth has never felt freer,” commented another friend as he relieved his face of his surgical mask before PE.

But with ‘social distancing’ and ‘disinfection’ as the buzzwords du jour, PE lessons have been modified to consist only of net barrier games, which involve minimal contact between students. Sports equipment is zealously disinfected after each lesson. Lab practical sessions, suspended before the circuit breaker, have also resumed with a new focus on the disinfection of lab apparatus and spacing out of students across lab benches.

A cynical part of me can’t help but dismiss these so-called security measures as little more than security theatre. But security theatre or not, these measures have left an indelible mark on the physical school campus. The mask I wear isn’t the only thing that feels stifling about this new school environment.

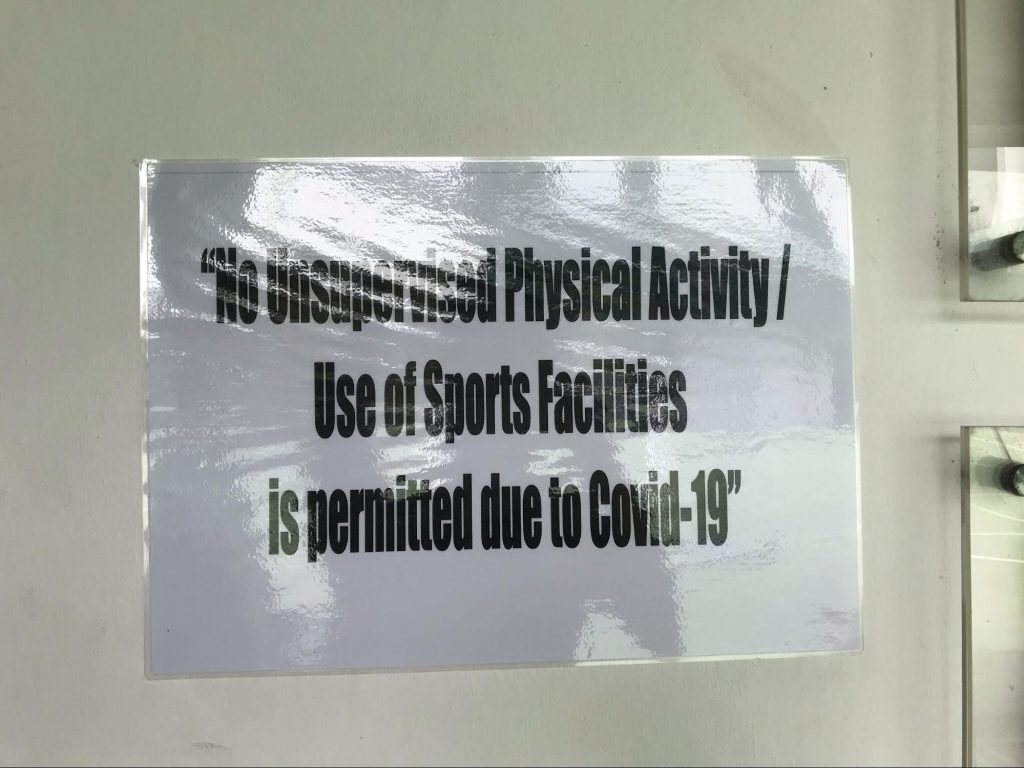

Students are no longer allowed to study in the school library, which remains open only for the loan of reference materials. Communal study areas have been cordoned off, sports facilities are out of bounds, and the lecture theatres sit as dusty and unused as they have been since February. Even the canteen has not been spared, with only about half the stalls operating due to the reduced demand and even then, only able to sell their food in pre-packaged bento boxes. The canteen tables have been pushed apart, the maximum seating capacity of three people per table meaning that many just grab their food and head back to class to eat.

Everywhere I look, there is something, formerly familiar, that has been newly cordoned off with tape.

The univiting physical landscape of the school sends a clear message: Attend your lessons, then go straight home. No reason to linger, nothing to see or do here. Schools have been reduced to mere facilities where lessons are produced. In a sense, they have become more like factories or plants instead of unique places imbued with student-run initiatives and coming-of-age memories.

With the pandemic expected to last for up to two years, many students will close this chapter of our lives with no memories of a normal JC experience to call our own. No morning assemblies, no CCAs. No lectures, no match supports, no concerts. No afternoons spent mugging with friends in school, or sitting for national exams in a sea of desks under the harsh glare of the school hall lights. No farewell assembly, no grad night.

As true as this is for me, it’s even truer for the JC 1 batch, who had their orientation cut short and for whom the word ‘lecture’ will conjure up memories of watching a pre-recorded video in a computer lab (due to the lack of available classrooms at the start of the year) with their classmates instead of one of scribbling notes on a tiny table while struggling to stay awake in a packed lecture theatre filled with their entire cohort.

And yet, in many ways, there are also signs that students have begun to embrace these changes as the new norm. Already, I have seen some interesting Instagram story videos pop up on my social media feed. These videos feature peers strutting down empty hallways with their whole squad at their backs, flashing peace signs and trying to look badass while the lower halves of their faces are hidden by masks. Other masked peers have posted TikTok videos of themselves dancing with friends in classrooms and empty stairwells. Birthdays also continue to be celebrated, albeit more furtively, in the canteen and in classrooms.

Even though our desks may be spaced one metre apart in exam-style seating, the reality is that students don’t spend their time seated at their desks all day. In the breaks between lessons, we quickly cave in to our natural desires to bridge the social distance, flitting from desk to desk to catch up with the friends we haven’t seen in months. We chat while eating, clearly not wearing masks as we do so.

Why would we take such risks despite knowing the threat that community transmission poses to our healthcare systems and our loved ones? There is something about seeing my classmates in the flesh that makes the threat of the coronavirus feel less real than the people I am seeing and speaking to. Surely, if there were any real threat, MOE would never have allowed us to return to school.

“As long as I’m wearing the mask, it’s in compliance with the rules.”

A month ago, I was so paranoid about catching Covid-19 that I refused to leave my house even to exercise at the neighbourhood park. Now, I’m taking public transport to school every day with nothing but a flimsy 2-ply surgical mask as a barrier between me and the world. The four weeks of home-based learning and four weeks of holidays that followed have started to feel like nothing but a hazy dream, or a distant memory of a time far gone.

Being back at school means I can do ‘normal things’ like have a meal outside of home and even take the MRT home with my friends. Meanwhile, those who aren’t schooling can’t even exercise at a park outside their neighbourhood or meet with friends living outside their household. It feels almost surreal how normal my life is in school. It’s almost as if my experience of the world has been divided firmly into two compartments: the world in school, and the world outside of it.

In school, it’s easy to believe that I am safe from Covid-19, that all these safe distancing measures are as arbitrary as the school rules which dictate that only black or white sports shoes are allowed, or that my hair must be tied up neatly. It’s easy to pretend that the masks we are all wearing are part of some new Korean trend, to convince myself that I am wearing a mask for the same reasons I’m wearing a school uniform—to fit in—and not because I am afraid of contracting a disease for which no known vaccine exists.

It’s only when I step out of school and walk past the closed retail stores, or read a Reddit post where someone is complaining about not being able to see his SO for two months that I remember: I am coexisting with a disease which has crippled the world economy and killed almost 400,000 people worldwide.

As a student, I’m one of the first people in Singapore to experience this return to some semblance of normalcy. But as restrictions are successively lifted, the boundaries of this ‘school bubble’ of normalcy will start to ripple outwards. Construction projects will gradually resume, people will return to their offices, shops will reopen. We might even have an election. New headlines that have nothing to do with Covid-19 will start to pop up on our news feeds amidst the daily reports of case counts and new regulations.

All this is already happening, and in a way it’s good because it means things in Singapore are returning to normal.

Your experience transitioning back into society could be like mine, or it could be entirely different. Perhaps you’ll return to the office to find that the pantry where you gossip over milo and biscuits is closed, that your usual workspace has been replaced with a gigantic red X made of non-metaphorical red tape. Or perhaps everything’s more or less gone back to normal. Squeezing with strangers on the MRT, cramming into lifts on the way up to your floor, and bumping shoulders when dabao-ing lunch back to eat in the office.

At the same time, the pandemic isn’t over until a vaccine is found. Until then, we remain vulnerable to a second wave of infections. This is not the time to be complacent. Even as we adapt to life with the new changes, we can’t brush off the lessons of hygiene and social responsibility that the circuit breaker has taught us.

On the way to class this Friday (our last day before starting HBL next week), a friend joked about the best way to eat a mango pudding without a spoon: “Put the container in your mask and, like, slurp it slowly during class.”

“Wait, but wouldn’t that get the mask wet and make it useless?”

He shrugged. “Yeah but I’m still wearing the mask. As long as I’m wearing the mask, it’s in compliance with the rules.”

As we battle the discomfort of wearing masks, it becomes harder and harder to remember why we’re wearing them. Already, the signs of fatigue are showing in supermarkets, where shoppers and stockers have stopped bothering with safe-distancing, and bus stops, where students crowd after dismissal, undermining the painstaking efforts to keep them carefully separated during the school day.

We need to remember that we are wearing masks not because we’ll be fined if we’re caught with our masks down, but because that’s how we can continue caring for the vulnerable people around us whose safety we were so worried about just a month ago.

I live with my 68-year-old grandmother, and the nagging worry that I might have contracted Covid-19 at school or on public transport often holds me back from giving her a hug when I return home. For her and her group of retiree friends, no longer being able to meet up with one another for yoga at the nature reserve has taken a toll on their mental and physical wellbeing. I really hope that we’ll eventually reach a stage where the elderly can leave the house to socialise with friends again without fear of catching the coronavirus.

It’s often been said that this pandemic could end socially before it ends medically. Reflecting on my experience, I can already see how this will be true. When we can’t change our external circumstances, we adapt to them. Getting used to life post-Covid-19 will be a necessary survival skill for all of us.

But in our hurry to get back to normal, let’s not forget what we have learned from the circuit breaker. For if we do, we’ll soon find ourselves back where we started: at home, isolated from friends and colleagues, with even more restrictions placed on us than before.

Are you looking forward to coming out of lockdown? Or do you think it’s too early? Share your thoughts with us at community@ricemedia.co.