All photos in this story were taken before the circuit breaker.

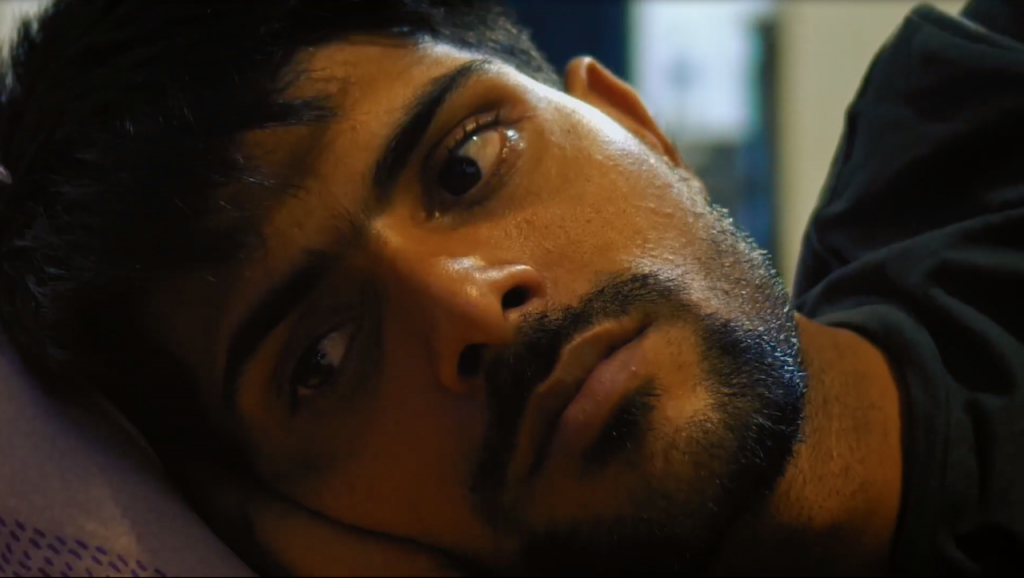

The last time Feroz* set foot outside his dormitory was in early April. For nearly four months, he has not been to Little India, the shipyard where he works, or even the other end of his dormitory compound.

After the circuit breaker kicked in on April 7, Feroz, a Bangladeshi migrant worker, watched as chaos descended on his Tuas dormitory and the place went into lockdown. With cases climbing day by day, he was moved to a room in another block in mid-April, meant for residents who had been exposed to the virus.

He has been there ever since.

For the last four months, he and his roommates have left their room only to collect their meals and use the bathroom. From his window, they can see barricades lining the compound; the blocks have been separated into red, green, and yellow zones depending on residents’ status. Optimism is in short supply.

“Still we don’t know what going on, and next day where we will be,” he tells me.

After Covid-19 hit the dormitories, early response efforts might be best characterised as disaster relief, focused on testing, controlling the outbreak, and keeping everyone fed and provided for. These initial challenges have been gradually resolved, only to be replaced by a different set of problems—some deadlier and harder to tackle than the virus itself.

Getting back to work

On July 25, it was reported that all dormitories are finally expected to be cleared of Covid-19 by August 7, apart from 17 blocks in several purpose-built facilities still serving as isolation quarters.

An MOM representative confirmed that this covers all migrant workers in purpose-built dormitories (PBDs), factory-converted dormitories (FCDs), and temporary living quarters. Due to the size of the PBDs, the biggest of which house tens of thousands of workers, clearance is done on a block-by-block basis to avoid holding the whole dorm up.

Although the process is nearly finished, and more men are expected to go back to work soon, being ‘cleared’ simply refers to a dormitory (or block) being declared free of Covid. It does not mean that men can immediately start work.

Nazmul*, who lives in a cleared PBD in Woodlands, estimated that around 30-40% of his dorm’s residents’ had returned to work at the time of our conversation. (He was not among them.) Being stuck in limbo has been agonizing for men like him and Feroz, who tested negative some time ago, but still don’t know when they can resume work.

The agencies involved have been working on a mammoth task under several constraints, and with extensive testing efforts, things have improved in the last few weeks. Nonetheless, migrant workers, employers, and community advocates I spoke to alike, while acknowledging the immense scale of the clearance process, expressed deep frustration over how it was managed.

By their accounts, the last few months have been a confusing mess, hampered by multiple communication failures and information gaps.

Several sources brought up inconsistencies and delays in how swab test results were communicated, particularly between the May—July period. (Accounts of administrative errors and delays with test results have also been reported elsewhere.)

Men were not always promptly informed that they had tested negative, adding to the chaos. They assumed this only because they had not been sent for treatment or heard otherwise, sometimes for as long as a few weeks, until their Covid status was confirmed. (Migrant workers can currently check this in an app, FWMOMCare, which allows them to check their health status and request teleconsultations.)

Even then, positive test results were not always promptly communicated. An owner of an engineering construction company, who asked to be known only as Ms Lee, claimed that her workers did not know they were Covid-positive for nearly 3-4 weeks after their swab tests.

They only learned this in mid-July, when they received letters from MOH explaining that they had in fact tested positive, but were no longer infectious because the isolation period had ended. The company had not known either, and only found out when the workers told them about the letters.

“You can’t imagine, we were all so angry and disappointed. I understand the dorm is locked down and not cleared yet, but as a mark of respect to the individuals … If someone’s positive he deserves to know, and not only tell him after he’s recovered,” she said.

After a dorm (or block) is cleared, a three-part administrative process must be completed before the men are allowed to work. Complicating matters is that even after this, work clearance status can change day-to-day, depending on whether the migrant worker has been re-exposed to the virus.

Ability to work has to be monitored daily via an app feature called Accesscode: green means go, red means no. (The feature was one of several apps, like FWMOMCare, which were rolled out by MOM and MOH to help improve access to information.)

While the measures are understandable, in view of preparing for a further wave of infections, the volatility has also caused headaches across the construction industry.

Ms Lee described how, just on the morning of our interview, her workers’ Accesscode statuses had all turned red around 6:00AM. “We all panicked, because work had already been arranged and scheduled,” she said.

They later learned that some residents at her workers’ dorm had been found to be infected, so the entire dorm was closed off as a precautionary measure. Ms Lee’s workers, who were not in the affected block, were eventually released around 10:00 or 11:00AM.

“You have to rearrange transport, explain to the clients … it affects business very badly,” she said.

A director of a construction company I spoke to, who declined to be named citing nondisclosure restrictions, shared that he had heard accounts of similar incidents. The disruptions, he added, were particularly ruinous for sub-contractors, for whom flexibility is key.

“I wouldn’t necessarily call [the response] heavy-handed, because if I were in the government’s shoes I would probably do the same thing,” he said.

“But I feel there has been a lack of empathy for what contractors are facing. And it’s hard on the workers. It’s hard for everyone.”

The deeper crisis: mental health

Beneath the battle against the virus is an even darker contagion.

In late May, migrant worker NGOs I reached out to unanimously expected their casework loads to rise, highlighting mental health as a major area of concern. They anticipated that delays in returning to work, the spectre of job losses, and a growing sense of powerlessness would be devastating for migrant workers’ mental health.

All this has unfortunately come to pass. Since April, NGOs and aid groups have seen a rise in migrant worker suicides, suicide attempts and ideation, and self-harm. Reports of such incidents have also been circulating in the press and on social media.

Sharif*, a migrant worker who is actively involved in volunteering within the community, and has helped counsel many fellow migrants, put it this way: “The situation is getting more normal day by day, but mental health is getting worse.”

(The morning of our interview, a video began circulating on social media of a migrant worker, allegedly from the Leo dormitory in Kaki Bukit, attempting to jump from his block. Two nights later, while I was working on this piece, a source closely involved in aid efforts informed me that another man attempted suicide on Sunday morning.)

Representatives from Healthserve told me they had observed a spike in anxiety amongst workers in June. While there was a slight drop in case numbers going into July, the intensity of the cases increased. The NGO has counselled around 700 migrant workers between mid-April to July.

They cited various reasons for this, including financial woes, worrying for their families back home in Bangladesh and India (where Covid-19 cases have ballooned), and the lack of information. However, what many have found most distressing is the absence of a clear timeline, causing a growing sense of helplessness—even abandonment—as the wait drags on, and on, and on.

Similar to how many Singaporeans felt when the circuit-breaker was extended in May, many migrant workers have been agitated by a sense that the goalposts keep moving. The Healthserve representatives shared that many workers were confused when their Stay-Home Notices expired, but they could not return to work—and when the circuit-breaker itself was lifted in June, and still nothing changed. Though the end might finally be in sight, the August 7 announcement was yet another double-edged sword.

“They keep using the dates as something to look forward to, like a checkpoint, but when it doesn’t happen and they don’t get released they feel so frustrated,” they said.

“Some have said things like, “We’ve been left to die, we feel like prisoners, we’re trapped.” Others don’t even want to talk to their families any more, because they feel low and don’t know how to explain what they’re going through.”

“Right now, mental health support is more important than food.”

Confinement has been particularly brutal for men in isolation in hotel rooms or cruise ships, where an endless wait— with no company but their own thoughts—wears away at even the strongest. Sharif described it as ‘worse than jail’.

Men in these facilities were mostly moved out there on account of being over 45 and high-risk. Those who tested positive were later moved out for treatment, but those who were negative were kept there—largely because, Sharif suspects, there might not have been anywhere for them to go. “If their dorm is still not clear, then they can’t go back. But where to put them?”

He described an attempted suicide case he had helped with just a few nights before, involving a man who had been isolated in a hotel room for nearly three months.

“I was very worried. When I talk to him he is not balanced, it’s like his brain can twist in a few seconds and he will jump,” he said.

“He told me, I’ve been living 3 months alone in a single room, I cannot tahan any more, I cannot sleep. If someone doesn’t bring me out tonight, I would rather die than stay here.”

According to the Healthserve representatives, the number of suicide assessments they conducted tripled in the week before we spoke. (They stressed, however, that the cases they see represent the extreme end of the spectrum, and that self-harm and suicide ideation have increased nationally, not solely within the migrant community.)

Despite months of intense community lobbying, it is unclear how, or when, the government plans to increase support for migrants’ mental health.

To date, there has been no explicit governmental action plan or timeline for one. When contacted for comment, an MOM representative referred me to their response to a Parliamentary Question from ex-NMP Anthea Ong from June 5, which mostly mentions NGO-led efforts.

Anthea, a prominent advocate for both mental health and the migrant community, believes that the mental health sector should be roped in to boost early-intervention care. Employers and operators also need to be involved in developing suicide prevention protocols.

“A holistic and coordinated response is urgently needed with upstream and downstream measures,” she told me, stressing the importance of educating migrant workers on early detection.

“Simply giving them hotlines to call without ‘teaching’ them how to identify warning signs in themselves and others is not going to effectively prevent more tragedies.”

Healthserve has also recommended that migrant workers’ access to both Covid-19 and mental health support be increased, and that cross-sector escalation and referral workflows are developed.

Echoing Anthea’s sentiments, Sharif emphasised that migrant workers’ mental health must be urgently prioritised.

“You have 300,000 workers. Some are strong but not all. Even the organisations who are involved can only help a few at a time. What is there now is not enough to be effective,” he said.

“After 3-4 months you need to help normalise the stress and anxiety before people can go back to work. All this is happening now because the longer the wait the higher the stress, they need help to transition,” he insisted.

“Right now, mental health support is more important than food.”

Freedom of movement

While more migrant workers will be able to go back to work soon, the community will continue to face movement restrictions for some time.

On June 2, amendments to the Employment of Foreign Manpower Act (EFMA) in the form of subsidiary legislation took effect. Key amongst the changes are clauses which state that migrant workers cannot leave their dormitories except with the permission of MOM and their employers, for medical treatment, or if required to evacuate. (They also make it a legal requirement for workers to ‘practice good hygiene’, ‘minimise physical interactions with other individuals’, and ‘keep their living space clean and tidy’.)

NGOs and migrant advocacy groups, while acknowledging the public health concerns, have been deeply alarmed by the changes.

These include fears over abuse of power, given how the changes effectively give employers absolute discretion over workers’ freedom to leave their dormitories, and whether adequate consideration has been given to their impact on migrant workers’ welfare and mental health.

“Migrant workers have faced far more draconian measures than everyone else … They know their employers forbid them from leaving their accommodation, and many have been threatened with severe punishments including deportation and blacklisting. This definitely instills fear, compounded by uncertainty. Clarity is lacking, not only in communication, but in the law itself,” said representatives from HOME.

Beyond the distress of confinement, movement restrictions have already caused significant difficulties for many migrant workers. Nazmul, for example, told me that his Work Permit expires in early August, but he has not heard if it will be renewed, and is trying to find a new job from his dorm.

HOME shared that they have heard from men facing similar difficulties, as well as others who were prevented from attending medical appointments or going to seek help at MOM.

MOM has since clarified that employers must ensure migrant workers only leave their dorms when their AccessCode statuses are green, to seek medical treatment (regardless of AccessCode status) or where required to evacuate, but cannot unilaterally restrict their movements for any other reasons. They also stated that the changes were communicated to employers, dormitory operators, and migrant workers.

Nonetheless, advocates remain worried over how aware migrant workers are of the measures. There is also a lack of clarity over how long the measures will remain in place, given that they have been formally entrenched in legislation.

MOM has indicated that the measures should be temporary, stating that the restrictions will be eased when infection levels within and outside the dormitories have remained low for a sufficient period of time, and that they will “amend or remove the work pass conditions when they are no longer relevant or necessary.”

However, it is unclear when this might be, or what it will be conditional on—or the toll the extra wait might take.

Salaries and job losses: the worst is yet to come

On top of all this, there is a consensus that the full brunt of Covid-19 has yet to be felt. Beneath the desire to get back to work are deeper, more disquieting fears: will we be paid? Will there even be jobs to go back to?

Of the four migrant workers I spoke to for this piece, two had received their basic pay for April to July, while the other two had pay cuts of 25%—50%. Although the latter felt the reductions were understandable, given that they had not been to work—and all of them were glad to have been paid at all—they were extremely anxious that things would deteriorate.

HOME shared that they had seen cases of unpaid wages over the circuit breaker, on top of workers who had had their permits cancelled shortly before and were left destitute. Similarly, both Ms Lee and the anonymous director, while stressing that they took their salary payment commitments seriously, were worried about the sustainability of the situation.

“Construction is basically cash flow management,” the director told me. He explained that main construction projects are paid monthly, while payments for subcontracting work arrive about three months afterwards. As a result, up till June, his company was still receiving money for work done between January to March.

But since no work was done from April to July, unless they can start work soon, they will have zero income for July to October. In essence, the company is hemorrhaging money, but none is coming in.

To help the beleaguered sector, the government waived the foreign worker levy and provided rebates of up to $750 per worker between the April—July period. (On August 1, shortly after my interviews, it was announced that the waiver and rebates would be extended till December 2020 and September 2020 respectively following industry pressure.)

While the assistance has been critical, it is unclear whether it will be enough, particularly once the levy is reinstated and the rebates are reduced to $90 per worker. The director pointed out that this amounts to only a fraction of the levy, and will not even cover a worker’s accommodation fees. To cover his outgoings, he has had to take out bridging loans, on top of the government assistance.

The bitter upshot of all this is that job losses are inevitable. When flights to India and Bangladesh resume, he anticipates that many companies will send workers back. NGOs fear that after months of anxiety and desperation, this could prove the tipping point for even more men.

“The construction sector was always headed for a meltdown, but Covid brought it forward,” the director said. “I would assume that most employers want to treat their workers well, though not all do. But in this climate, I think a lot of good employers are going to be forced to do things they’re not proud of.”

The worst part, he added, is that recently-arrived workers with little experience are likely to suffer most.

“Migrant workers are often the breadwinners for their families, but as a boss, if you have to let someone go, of course it’s the new guy rather than the one with 8 years’ experience,” he said.

“And you know how much they have to pay in agent fees to come here. The new guy probably won’t even have paid off his debts.”

Feroz eventually tested negative for the virus around late June. Today, he and his roommates continue their wait for news: whether they will be moved out, when they can go back to work. In the meantime, the days tick by identically.

On the morning of Hari Raya Haji, I ask if he’s planning to celebrate in any way. “Nope, just morning I pray, and [sleep] back”, he texts back, adding a laugh-crying emoji.

Months of unstinting grimness have driven many migrant workers to the brink. For men accustomed to hard labour, they are not immune to despair or grief; they have their moments of hopelessness like all of us.

Still, while their suffering must not be normalised, the crisis has also brought out the community’s extraordinary resilience.

There’s Sharif, taking calls from desperate countrymen in the middle of the night. Nazmul, who insists that he loves Singapore, and wants to stay here and work. Nasir*, another migrant friend, tells me that dance has kept him sane through the darkness of the last few months. “I can’t explain … only I know when I dance I [feel] very happy and enjoy. Nothing come my head inside,” he texts me (also adding a laugh-crying emoji).

To pass the time, Feroz writes songs, or studies for an engineering course he’s taking. In the evenings, he plays Bengali folk songs on his guitar to try to lift his roommates’ spirits.

“I’m all right, cause I have my guitar with me I can make music … I’m used to stay alone cause I’m a lyrics writer, I have my own world,” he texts me.

“But I dunno about the others. They look so different. Worried. Mentally [their] situation is not good.”

We reached out to MOH for comment, but did not receive a response in time for publication. We will update the piece accordingly if a response is received.

If you know a migrant worker in need of assistance, please contact the following helplines:

Healthserve: +65 3138 4443

HOME: 6341 5535

TWC2: 6297 7564

Migrant Workers’ Centre: 6536 2692

—

What are your thoughts on the migrant worker situation? Tell us at community@ricemedia.co.