All images by Zachary Tang, unless otherwise stated.

Jing was relieved. Tim was the first client she ever broke the news to, and his response made her feel that her nerve-racking hours—spent practising how to deliver the information accurately and empathetically—were not spent in vain.

But she soon found out that it was not how she talked to Tim that left an impression. Instead, what mattered was a mundane act that she carried out reflexively.

“He seemed like he couldn’t talk,” she recalls, “so I asked him if he would like to have a drink.”

And it was this offer of a glass of water that Tim had remembered, and which had touched him the most.

In that moment, Jing realised that when receiving such devastating news, people don’t necessarily want all the information. Rather, they need to know that they are in a safe space where they will not be treated differently, and can receive help and emotional support.

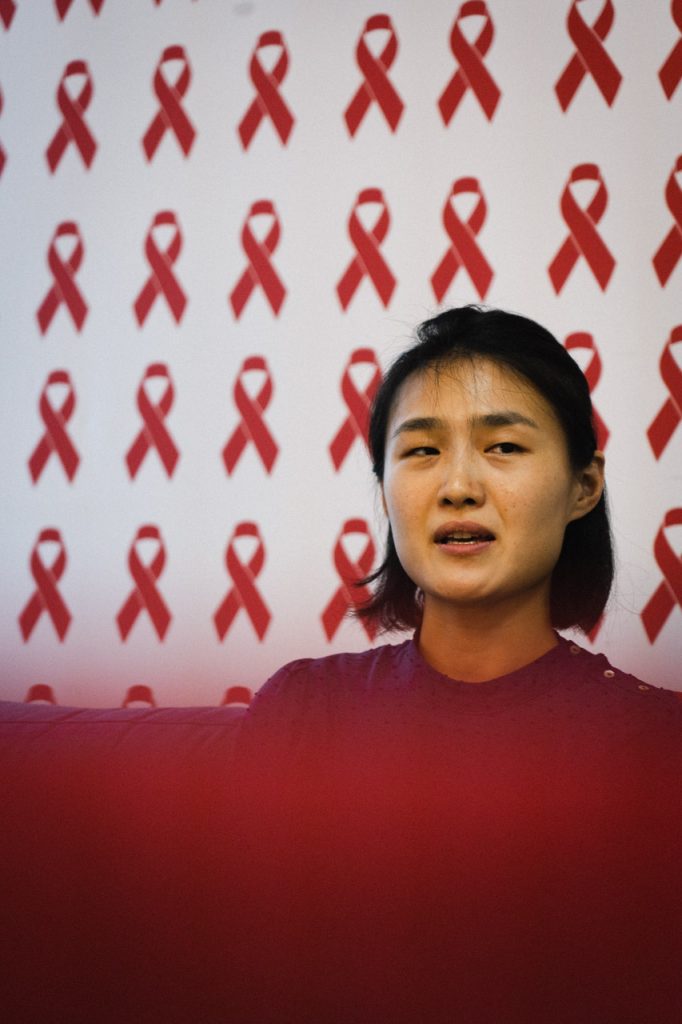

For over 30 years, this is precisely what Action for AIDS Singapore (AfA), a non-governmental organisation that combats HIV in Singapore, has been doing for the community.

Jing is a senior executive at AfA where she, along with other full-time staff and volunteers, organises the anonymous testing service, runs outreach and education programmes, and does HIV advocacy work.

Such measures are crucial because a HIV infection is one of the least understood and most stigmatised diseases in Singapore. Even today, when everyone is a self-certified doctor thanks to WebMD, AfA still gets calls from the public, panicking that they might catch the virus because they had inadvertently shared a bowl of tau huay with a HIV-positive person.

Jing sighs: “After 30 years, we still get questions like that.”

If someone were to test positive for HIV in the 1980s, there was a 95.5% chance they would die from that infection. In the 2000s, that number dropped to 22.6%. A scientific paper puts the statistics in perspective: from 1990 to 2011, the decrease in HIV-attributable deaths dropped by 89%.

Sumita Banerjee, the executive director of AfA explains: “In the 80s, 90s, [HIV] was a death sentence. Today, if a person is diagnosed early and is on treatment, they can have the same quality of life and life expectancy as any other person.”

For this dramatic improvement in treatment, we have biomedical advancements to thank. New antiretroviral drugs are more efficacious in suppressing HIV. Moreover, they combine two or more medications into one pill, and have fewer potential side effects, which makes it easier for HIV-positive people to adhere to treatment.

In fact, antiretroviral therapy of HIV can be so effective that within six months of taking HIV medication daily, the virus can be undetectable in the bloodstream of a HIV-positive person. And when the viral load is undetectable, the virus is untransmittable to anyone else (a phenomenon known as U=U). That means a HIV-positive person—who has acquired viral load suppression—can have unprotected sexual intercourse with their partner without transmitting HIV to them. (Although this is not recommended as the risks of other sexually transmitted infections remain with unprotected sex.)

In other words, being HIV-positive today is just like living with high cholesterol, diabetes, or any other chronic illness: manageable and not necessarily life-threatening, as long as the patient checks in regularly with a medical professional.

(To clarify, being HIV-positive is not the same as having AIDS. HIV stands for human immunodeficiency virus; as its name suggests, it is a virus that attacks human cells. AIDS is an acronym for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, which is a fatal stage of infection that a HIV-positive person can develop if they do not undergo treatment.)

John couldn’t imagine. To him, it was a sentence worse than being HIV-positive.

Like John, for many people today, the stigma that they will face is more traumatic than being diagnosed with HIV.

Recall Jing’s anecdote about offering a glass of water to Tim. If someone had done that for me in a time of crisis, I would feel grateful too. But it probably would not have left as deep an impression as it did on Tim—I suspect he was so moved by Jing’s gesture because he was expecting his diagnosis to excommunicate him from society. Yet Jing afforded him kindness despite his status as a newly diagnosed HIV-positive person. She didn’t treat him as any less a human being.

Not everyone is as lucky.

Eight years ago, the first question people asked upon learning they are HIV-positive was: “How long do I have?” Nowadays, it’s more along the lines of: “Will my boss know? Will I be fired?”

Worrying about job stability is an unequivocal improvement over confronting certain death. But when the fear of being judged by others overshadows concerns over your own health, it tells us that society has not kept up with the pace at which medical sciences have matured.

As Jing puts it, “the virus doesn’t kill. The stigma does.”

But some stigma is also caused directly by Singapore’s anachronistic laws and policies as well.

Take Section 377A, which criminalises sex between consenting adult men. Men who have sex with men (MSM) belong to a population particularly at risk of contracting HIV, yet they may eschew regular testing and treatment because they are afraid of disclosing their sexuality. Furthermore, with the unfair association of HIV as a “gay disease”, it is not unheard of for ignorant people to accuse homosexual men as “deserving” HIV as a form of penance.

When it was reported that Mikhy Farrera Brochez had obtained Singapore’s confidential HIV registry and was threatening to leak the personal information of people on the list, AfA was inundated by people who were terrified that they were going to lose their jobs and their friends.

In a world with perfect information, the mere disclosure of names should not cause such panic. As aforementioned, being HIV-positive is like managing any chronic health condition. But the existence of a registry instills fears: it says that the HIV-positive population is one that needs to be monitored and controlled.

Sumita says that many countries or states do not collect nor maintain a database with particulars of HIV-positive people, which prevents them from feeling like they are singled out on a (very literal) list.

Yes, there is indubitably a case to be made for the existence of such a registry. Dr Leong Hoe Nam, an infectious disease specialist from Mount Elizabeth Novena Hospital, tells CNA that monitoring the number of patients and transmission rates of HIV “allows the Government to decide the amount of resources to direct to control the illness, and project healthcare costs.” The data, when used appropriately, can help to curb the spread of HIV and improve treatment of patients.

What, then, is appropriate use of data, in terms of a national registry of HIV-positive people? In Florida, the names of patients are not disclosed to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, which maintains the registry. In other words, patients are anonymously identified, their data analysed on an aggregate—and ethical—basis.

Unlike Singapore’s registry, no names are involved.

Doctors in Singapore agree that such an approach is sufficient. To that I would add, “necessary”. In the same CNA article, Dr Leong “argued that tracking trends does not require patients’ personal particulars”.

This sentiment is shared by Sumita: “We don’t need names anywhere. If they need to track, it could just be 3 numbers of the NRIC.” Indeed, doing away with personally identifiable information is something AfA supports. But she seems resigned to the fact that it is “beyond [their] purview”.

“That’s more for policy change,” Sumita says. But, personally, I’m not holding my breath.

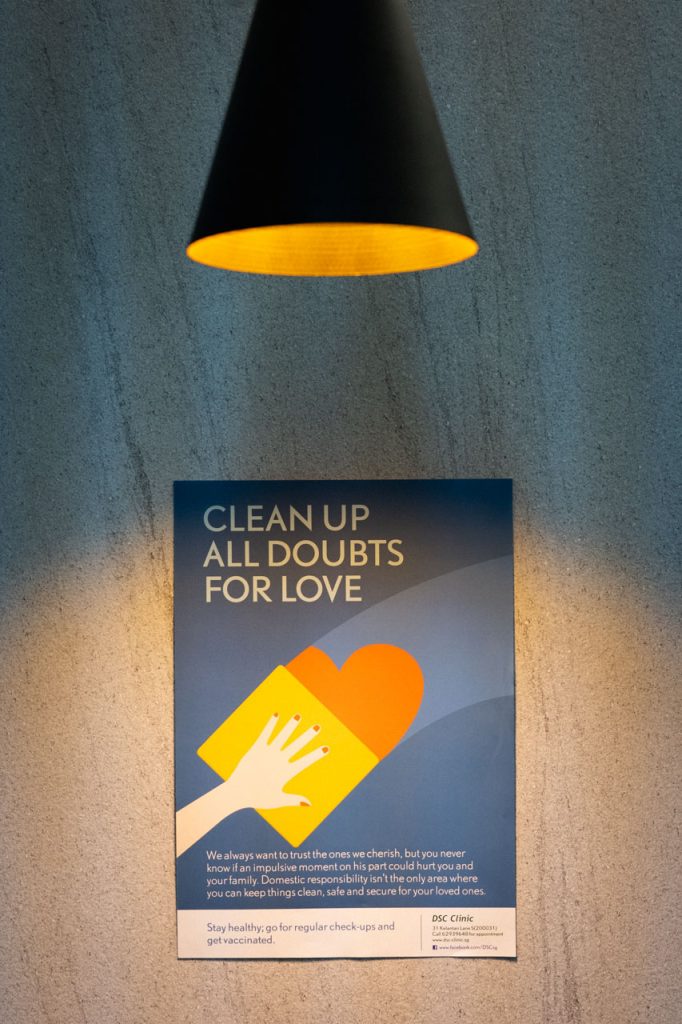

The first provides training to healthcare professionals so they can manage potential HIV cases with more sensitivity and up-to-date information. General practitioners (GPs) in Singapore, AfA has found, may lack information regarding the advances in HIV treatment and prevention (such as pre-exposure prophylaxis, more commonly known as PrEP, which can reduce the risk of HIV transmission by 99%).

Even if GPs are equipped with such knowledge, they may not know how to talk to patients in a way that does not condescend or judge. Given that GPs are usually the first medical professional Singaporeans visit when they fall ill, this is a huge lacuna in the support structure that AfA is plugging.

The second is a web-based portal that consolidates all the information a newly diagnosed person needs. Sumita says it will cover not only medical information like how to find and maintain treatment, but also educate people on their legal rights and subsidies available to them. In addition, the portal will highlight positive (in both senses of the word) role models, demonstrating that HIV-positive people can continue to lead fulfilling and healthy lives and share it with a loved one.

Honestly speaking, I was skeptical when I was listening to Sumita describe the portal. How is a website a groundbreaking project that deserves funding from an international organisation? So I played the devil’s advocate and asked her how this portal is different from any other I can find within 5 seconds of using Google.

5 seconds later, I realised that, in 2020, you can watch someone eat a sea slug live on Instagram, but there is still no Singapore-based website that provides all this relevant information to HIV-positive individuals. Equally missing are Singaporeans who have publicly “come out” as HIV-positive: Jing and Sumita mention that only a handful have come out in the last few years, which explains the isolation and stigma HIV-positive people encounter. AfA’s portal, then, is a long time coming.

But in the long run, their goal is much more ambitious: AfA wants to end HIV in Singapore by 2030. To that end, they have come up with a detailed community blueprint that sketches out the measures and key populations they will be targeting within this decade.

Sumita is optimistic—and adamant—that their objective is realistic.

“We know we have all the tools in our hands to end HIV. But what we need is the right kind of coordination, collaboration, and resources. [We need to] work with all stakeholders, the public and the private sector. And hopefully we will end HIV in the next 10 years.”

“Then I will be out of a job,” Jing laughs.

“But I will be happy.”

Know anyone living with HIV? Find them and give them a hug. Then tell us how you think we can further demolish the stigma against HIV in Singapore by dropping us a note at community@ricemedia.co