This is Part Two of a two-part series; you can read Part One here.

I’d never heard of the term before, but upon looking it up, my heart sank in recognition. The state, which is characterised by feelings of powerlessness in the face of inescapable adversity, is one that sounds all too familiar. Over the course of my interviews, the attitude I encountered the most—more than frustration or bitterness or anger—was resignation.

The story goes like this. In the mid-1960s, Dr. Martin Seligman, a psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania, began a series of experiments on dogs as part of his research into trauma, depression, and conditioned responses.

Seligman and his colleagues divided their test dogs into three groups. In the first stage of their study, they left the dogs in Group 1 alone, and subjected the dogs in Group 2 to electric shocks, which they could end by pushing a lever. Meanwhile, the dogs in Group 3 were given shocks of similar intensity and length, but without the means to stop them.

In the second stage of the experiment, the dogs were placed in a Pavlovian shuttle box—a chamber with a partition dividing it into two sections—and subjected, once again, to electric shocks.

The dogs in Groups 1 and 2, upon being shocked, ran around in pain and fear before realising they could escape by jumping over the partition. By contrast, the researchers observed that the Group 3 dogs quickly stopped howling or running around; they simply waited, whining quietly, until the shocks terminated. In other words, having previously come to believe that they could not avoid the shocks, they simply gave up and accepted their fates. Seligman dubbed this response ‘learned helplessness’.

None of this should be taken to mean that my interviewees are sapped of all agency, or that they are passive characters content to be pushed around their own lives by external forces. Rather, they all demonstrated a resourcefulness in working around the restrictions placed on them. But the desire to just accept the status quo and move on with their lives, in the belief that the battle for LGBTQ rights might never be won, was a view I encountered more than once.

It’s been more than a decade since Pink Dot began, she notes, and 377A shows no sign of being repealed any time soon. Other rights, like access to public housing, marriage, and equality legislation, remain distant dreams. “I know every person counts, but we’ve been fighting for so long and nothing has moved.”

The time has come for her, she feels, to move on with her life. “I have other responsibilities I want to focus on now,” she says, taking Nic’s hand. “I’m happy in my bubble [with Nic], and I feel like if the world’s not going to change, I’ll just do what I can on my own … do what I can to live my life happily.”

This inclination towards self-preservation is shared by Carrie, the trans woman. “Some [trans people] are okay with being out and doing activist stuff, but it depends on the person. For me personally, I just want to assimilate, because the way I see it is,”—my heart twists as she says the words— “I don’t think things here will change much.”

At the other end of the age spectrum, this reluctance is echoed, albeit for slightly different reasons, by Richard, a 63-year-old cisgender gay man whom I’d met at Pink Dot. In a sea of under-35s, he’d stood out like the white bud at the heart of a bougainvillea.

As a longtime member of the arts community—Richard is a retired choreographer—it bears mentioning that ‘outness’, to some degree, has been less fraught for him than most. It’s a stroke of luck of which he is well aware. The words ‘lucky’ and ‘fortunate’ crop up a lot during our conversation, and he notes that “[c]reative people, arts scene people, tend to be more open-minded.”

For him, the decision to hold back is part age—having mellowed with time—and part pragmatism.

“I think for people in the silver generation, we’ve seen the world evolve and change,” he reflects. “We don’t have to be so ‘out and loud’, put ourselves out there and fight for the cause, because we’ve already found ways of living our lives and getting by.”

“I think it [activism] gets tiring after a while,” reflects Carrie. Moreover, she notes, advocacy —which would necessarily entail identifying herself as a trans woman—would upset the careful equilibrium she’s reached. After years of struggling with her gender identity and enduring taunts from strangers, hormone therapy and other personal changes allow her to pass nearly all the time as a cisgender woman—the one thing she’s wanted all along.

“I’m at a point where I don’t think about [being trans] that much anymore. I don’t really have much that I want to change, and anyway, I would rather be seen as a woman than as trans,” she tells me.

Nic and Jackie’s concerns, meanwhile, stem from the pressures and assumptions lumped on LGBTQ people in the public eye.

“If you’re a gay person in the spotlight, you will automatically be treated as representative of the community,” says Nic. “And once you have all those eyes on you, if you step out of line, everything will regress.”

“I’ve wondered why I don’t put myself out there more,” she continues. Her coming-out story, she points out, was one of hope; should she have done more with it, put it out there to show people that yes, you can be Catholic and brown and mixed-race and gay?

“But I guess I just got to a point where I was like, okay, that’s not me. I’ve never wanted to attract that kind of attention—to put myself in a position where I’ll have people rooting for me to mess up, just so they can prove a point.”

She brings up Li Huanwu’s recent marriage as an example.

“I feel so bad for him. If he does something that’s a bit too controversial, puts one toe out of line, people will be like, OMG, gay rights have gone too far,” she says.

“If he gets a divorce in the next two years—we’ll be screwed. Like, see lah, you think gay people should be able to get married? Gay people in the public eye get made examples of.”

There is no escaping that activism carries heavy demands. It cannot be done without a cost to oneself, and to be able or willing to afford it requires either privilege, extraordinary selflessness, or the belief that one has nothing more to lose. It is a tremendous ask of people already in marginalised positions, who must exist as it is in a society that is constantly trying to undermine them.

Nonetheless, I point out to Nic and Jackie: surely Li Huanwu would not be held to such impossible standards if more people came forward to normalise gay marriage. And ultimately, if no-one is willing to take up the fight, where would that leave everyone? How would things ever get better?

“I know someone needs to fight for this,” Jackie says, sucking in a breath. “I know. But it’s hard enough as it is.”

Why, in other words, should this be asked of LGBTQ people in the first place?

“The question I would put to the government is this: how many hoops do you want us to jump through? What would we have to tick on your check lists for you to take us seriously?”

“We’ve bent over backwards, given you reasons, shown that same-sex families can work. What more do you need us to prove to you?”

So if they could, they would leave.

Every single one of my interviewees tells me that were the option available to them, they would leave Singapore. It is a common denominator I did not expect to find.

Take Richard, for example. Even though he’s enjoyed, by his own measure, a rich and meaningful life here; even though he has friends here whom he adores and work he enjoys; even though he’s choreographed for multiple national events, he would leave if he could.

In his 20s, he lived in the Philippines for five years, having received a scholarship to further his studies in dance there. Although he eventually re-adapted to life in Singapore, the homesickness for his life abroad when he first returned (in part for work, and in part to care for his ageing grandmother) was so crippling that he wanted, in his own words, “to take the next plane and get out of here”. It was a feeling he never forgot.

“The only thing holding me back now is my old folks,” Richard explains. His mother has dementia and severe osteoporosis, and his dad is recovering from a stroke. And he wants to be here to look after them. When they eventually pass on, however, he’ll leave, maybe to Taiwan.

“Maybe in five years,” he adds.

Carrie and Clement (the cis gay man and Pink Dot spokesperson) can’t leave just yet. The former has another year of university to finish, and Clement’s partner has a good job here which he doesn’t want to give up.

But after she graduates, works for a few years, and has some money saved up, Carrie will focus on moving overseas with her boyfriend. While Clement and his partner might stay put for now, he tells me that “[i]f we were to have a conversation next week about whether we should move somewhere else, I’d be like, why not?”

On Nic and Jackie’s part, moving will have to wait till further down the road. Like Richard, they want to be here for their parents in their golden years. To this end, despite their frustration with the status quo, they acknowledge that life in Singapore has things to be grateful for.

“Singapore is a great place to live, I definitely agree with that,” Jackie says, citing public transport, food, and in particular, safety, as things she appreciates about living here. Nic, who does not present as conventionally feminine, notes that she can walk down the street without fear of being assaulted or harassed.

Still, she says, “[i]t’s just harder for us here. I wouldn’t want to leave because it’s a bad country, I would leave because I can’t have a family and live out my life with my partner the way all these people get to do.”

“I think back in their day, when Pink Dot first started, there was a lot of energy and excitement, wanting to see what happens … that change seemed possible, that it would maybe even happen in their lifetime. And now … now,”— he pauses—“To be honest, I can’t really find the words for how visceral their anger with Singapore is.”

These men and women, he says, are all brilliant, talented, creative individuals, many of whom gave up opportunities to move abroad to stay and make their lives here. Whether out of patriotism or for their families, or out of hope that things would get better, they stayed. They put down roots and did their best to help them grow.

And now, after 11 years of watching the dot reform and scatter, with the needle barely having moved an inch, they are asking: what was that for?

“All of them have had it. They’re making moves to leave the country forever,” he tells me. “It’s not that they don’t want to live in Singapore any more … if I could summarise it, it’s more like they don’t want to die in Singapore.”

“When they’re talking about where they want to spend the rest of their lives,” he says, “They really mean the rest of their lives. Where do they want to be when they close their eyes? Is it really going to be here?”

He had only just come out to himself at the time, he says, after years of denial and self-described ‘mental gymnastics’. He remembers opening the Sunday Times and seeing a little write-up at the corner of the page: 2,500 people had gathered in Hong Lim Park the day before.

“I remember thinking how extraordinary this was,” he says. “At the time, there wasn’t even a handful of people in my life who knew I was gay. And overnight, I went from that to suddenly knowing that there were 2,500 people who would be okay with it. I just hadn’t met them yet.”

His foot jogs up and down as he says this, literally thrumming with uncontainable energy.

As the only one of my interviewees to be engaged in LGBTQ activism (though all his comments were made to me in a personal capacity), I’m particularly interested in what he has to say. For him, activism was a way of channelling his “deep-seated angst” about returning to Singapore after the relative freedom he’d enjoyed while attending university overseas.

“I never bought the idea of youths being apolitical or disengaged,” he says, as we exchange a mutual eye-roll over millennial stereotypes. “All the signs point to the opposite. We care about things that are bigger than us, which is why there are so many LGBTQ groups on campuses.”

I tell him about everything I’ve seen and heard from my interviewees so far: the frustration, the bitterness, the anger, and above all, the sense of hopelessness, which was by far the hardest thing to stomach. Maybe it’s my straight privilege showing, but knowing this made it difficult for me, I admit, to roam around Hong Lim Park on the day of Pink Dot, taking in the thousands of bright-eyed faces, the undimmed joy in their eyes.

Would they still feel this way, I wondered, 10 years down the road? When life has continued to disappoint them, and they have been repeatedly ground down, and the battle for equal rights no longer seems like a winnable fight, but an exercise in futility?

He stops bouncing in his seat momentarily, and takes a moment to gather his thoughts before answering.

The question of how much inequality anyone can be expected to stomach before giving up is a very real one, he says, and a sentiment he understands himself (he would leave if he could, after all). To this end, it’s also true that 377A, despite its massive significance, is but one instance of entrenched legal and policy discrimination.

“I don’t think anyone’s under any illusions that if 377A is repealed, homophobia will magically evaporate and queer liberation will be achieved and unicorns will rise from the ashes.”

It might not be taken off the books for a very long time, he admits. Maybe another 20, 30 Pink Dots will come and go before this happens; maybe fewer, maybe more. Maybe he won’t even be alive by the time real change takes place.

But to him, the sea of young faces at Hong Lim Park represents a generation of people that not only believes but expects different things of the world they live in. It’s these people who will one day comprise a significant proportion of our workforce, our society, our communities; who have a very clear vision of what the world should be like, and who are powerful and resourceful enough to make it happen.

He believes in them. He’s one of them, after all.

To this end, he acknowledges that LGBTQ activism, for the most part, is a young people’s movement—but this isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

“I think you can look at this youth idealism in two ways. You can either see it as being the folly of youth or doomed to fail, but I don’t think so. In my opinion, that would be really dismissive.” He quotes Angela Davis at me: you either accept the things you cannot change, or change the things you cannot accept. He’s chosen the latter.

“I think if anything, it’s very important not to succumb to that fatalist, ‘this is all we have’ point of view. It is all we have, but what we have is precious, and if we didn’t have it, we’d be worse off,” he says.

“It’s important to hold on to it, and try to grow it and build on it, and if that isn’t enough for you then that’s great. It means your hunger for change has outstripped what you have created.”

“Gay seniors,” it reads.

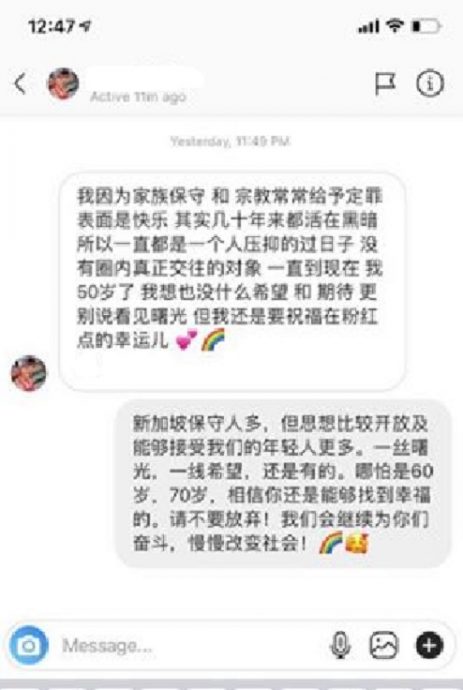

He’s appended a screenshot of a message which was sent to Pink Dot’s official Instagram account:

“My family is conservative, and my religion sees me as a sinner. On the surface I am happy, but for many decades I have been living in darkness, in an oppressed environment. I have never really dated in the community. I am now 50, and I don’t think there is any more hope, and I don’t see any light at the end of the tunnel any more. But I still want to wish the best for all the lucky ones at Pink Dot.”

It stops me in my tracks. My vision goes soft so quickly that I don’t even register I’m crying.

But this experience, I realise, is something my interviewees have all been through already. It’s one they know all too well. They have endured it for years. They have been conditioned into doing so by the very society they live in, and the very government whose policies they live under, and the cruelty of this is more devastating than I know how to put into words.

In this vein, there is a postscript to the Seligman story. His research with the dogs was a seminal one for psychology; it made his name virtually synonymous with ‘learned helplessness’ for decades. But if helplessness could be conditioned, Seligman reasoned, so could hope. He went on to become the father of the positive psychology movement.

And hope, as two young activists would articulate decades later, is not something we are given; it is something we must create. This, perhaps, is the hardest fight of all.

Have something you’d like to say? Tell us what you thought of this story at community@ricemedia.co.