The following story is told in Azizul’s voice.

It’s been a slow year. I mean, Covid-19 slow, i.e. a glacial pace except even slower. So, on top of the usual job search, I started to look for things to do with my time. I knew, off the top of my head, that Singapore is a biomedical hub. And never has there been a time when I was so free.

So off I went to consult the algorithmic gods of Google. I typed: “human medical trials”.

There were a few options. I submitted my name to a few of these places, not knowing what to expect.

That’s how I found myself in a Covid medical trial.

It was only then when they finally revealed it was Covid-related. The purpose of the trial was to, across several batches of guinea pigs—I mean test subjects—try to find the safety limit, the maximum dose of the antibody in humans. In injecting us with Covid antibodies, the study focused on testing the side effects, not the efficacy of the treatment.

If I was still interested, I could sign up.

One or two people left.

I decided to stay. What did I have to lose, right?

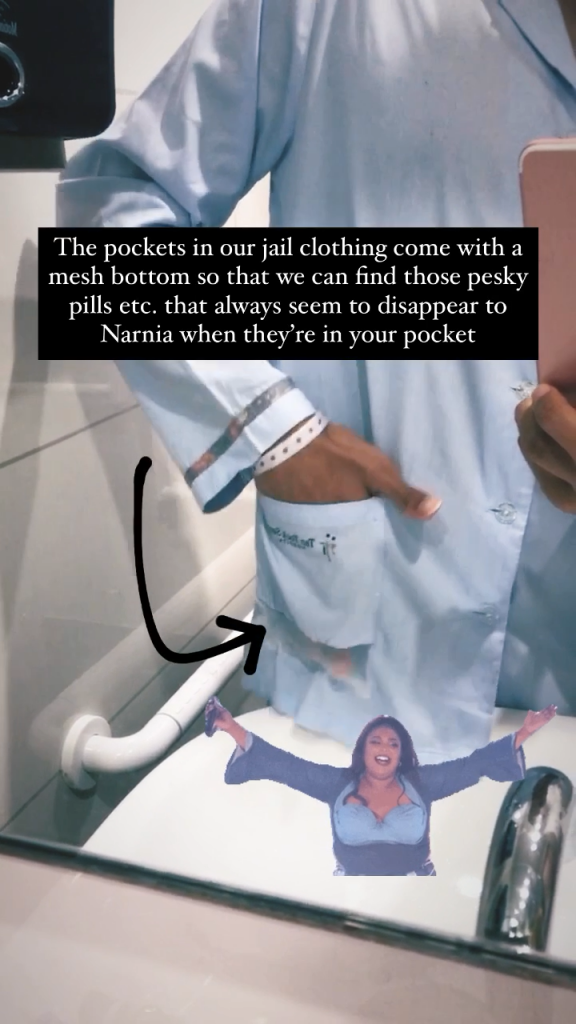

The room we were staying in was like an A2 ward, with two beds and one toilet in the room. The walls were completely glass and in view of the central nurses’ station, but when it’s time to sleep you can draw the curtains.

It was spacious enough such that when we were in our own area we didn’t have to wear masks. So I felt like I was at home because I could hang around in bed and not be masked up until other people were around.

It was basically a paid staycation, in the company of people I didn’t choose, and in return for me donating my body to medical science.

Laughter.

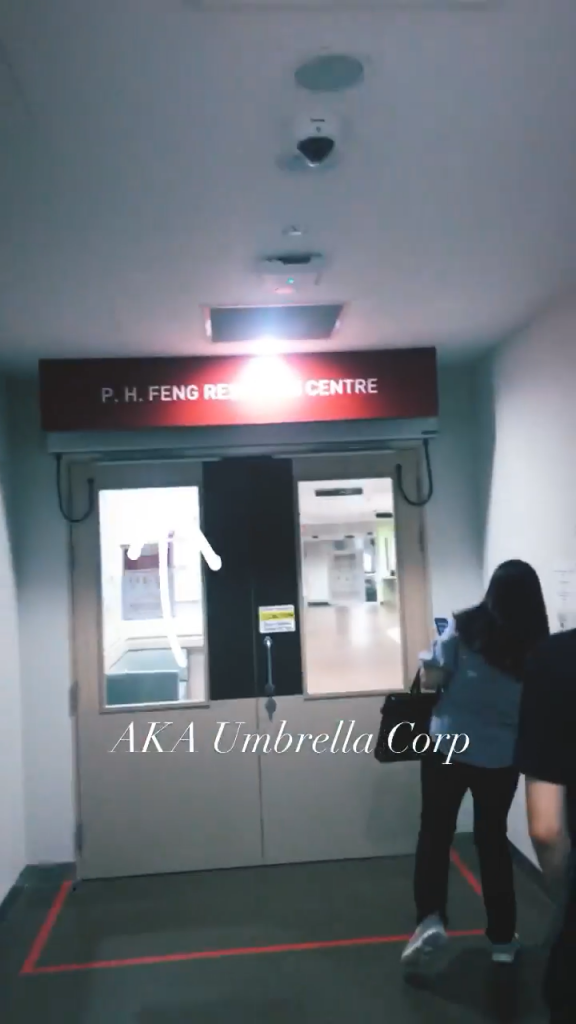

When I showed up, I had to get swabbed for Covid. The test itself … was a novel experience. For someone who hasn’t been swabbed before, it was like, ‘Oh my god, what’s going on?’ The nurses bring you to a hermetically sealed room; everyone is in a hazmat suit … It feels like you’re in Resident Evil. I felt like I was in Umbrella Corporation and I was going to be experimented on. Which I guess was true.

One thing about the hazmat suits was that the plastic visors didn’t obscure their oddly eager faces. Why were they looking so pleased before assaulting my person?

Before the nurses swabbed me, they passed me a tissue.

I asked, “Why do I need a tissue?”

They replied, “In case you cry.”

“Why would I be crying?”

“You’ll see.”

More uncomfortable laughter.

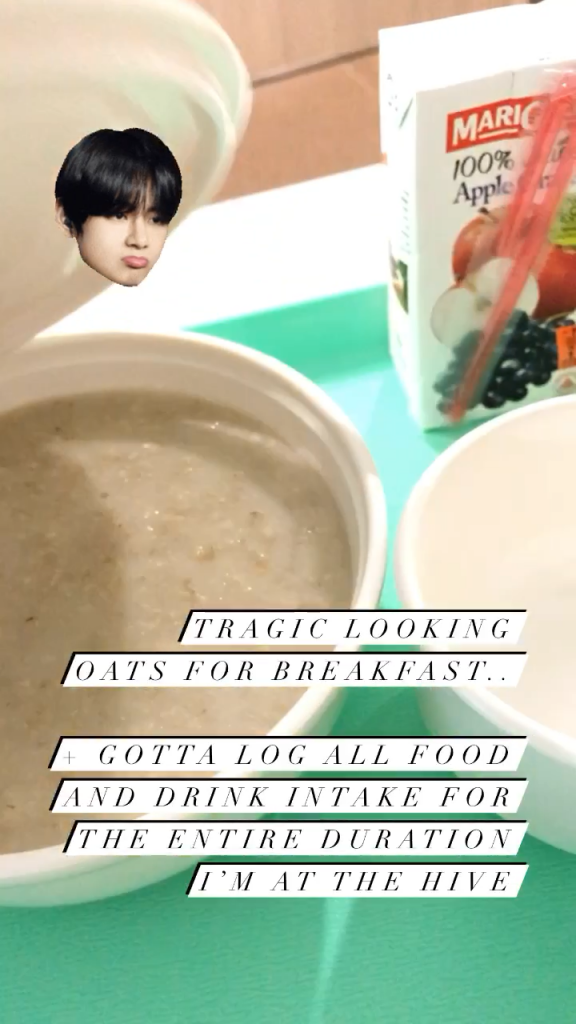

For example, food, because we were under a strict diet of 1800 calories a day. Which is very little. Two Extra Value Meals, maximum.

It was terrible. Our first meal was really depressing. We had to fast the night before we checked in because they needed to draw our blood the moment we arrived. I fasted, looking forward to the breakfast.

Oh my god. Awful. Wow. It was oats with Equal, the sweetener … it was basically just dust.

A porridge of dust.

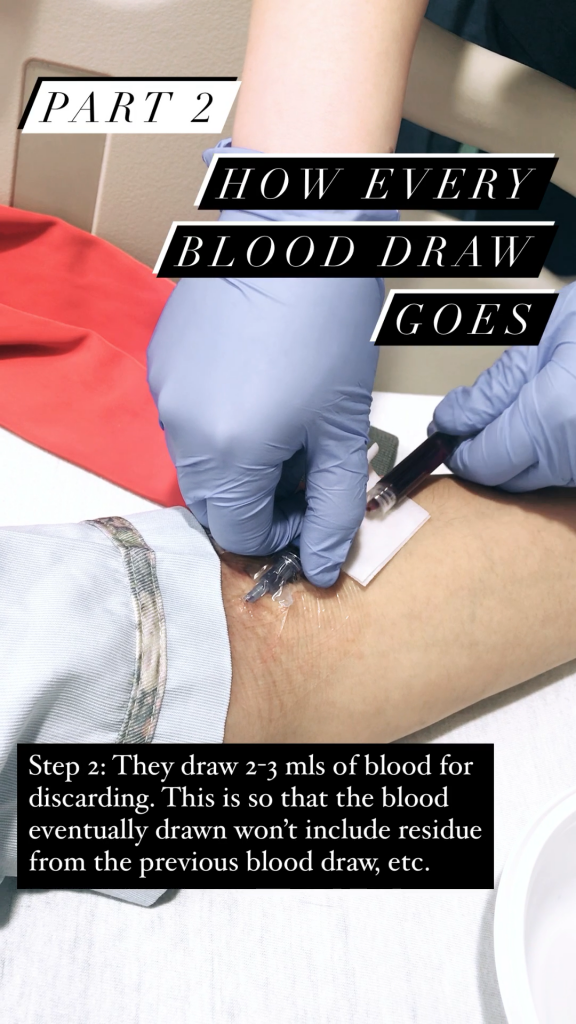

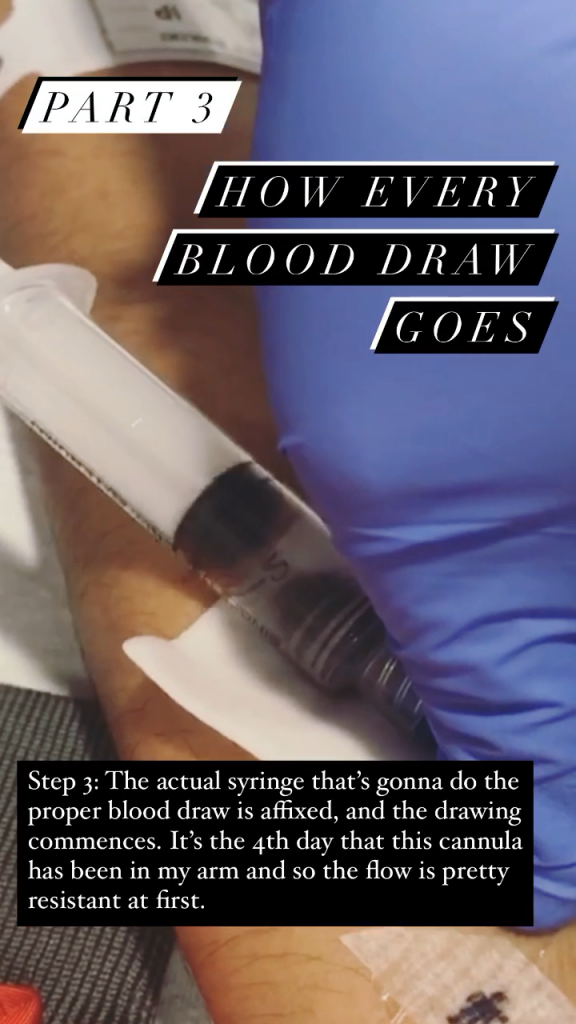

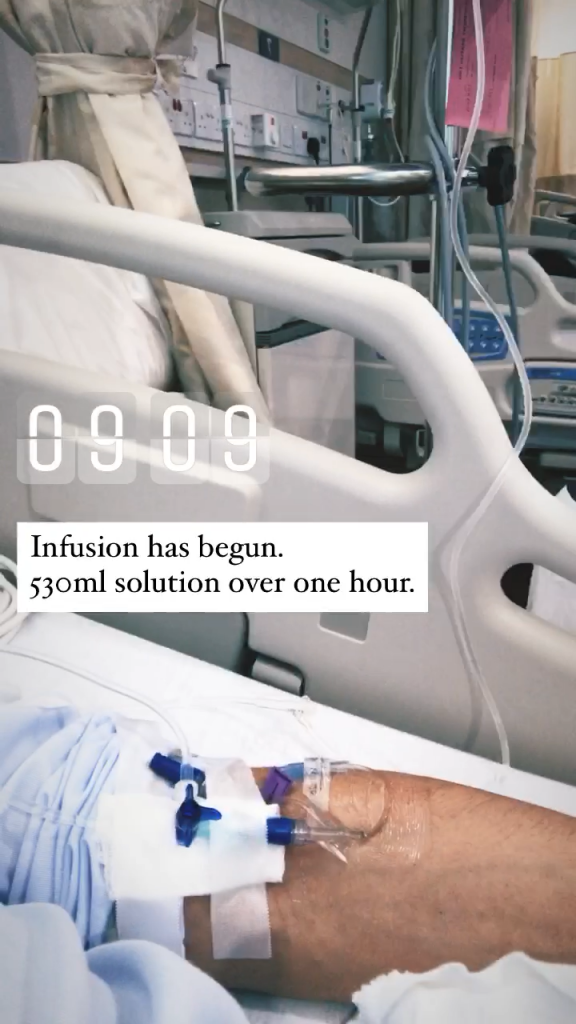

They had to draw the most blood from us—every two hours—to check the key markers in our blood because we were injected with the Covid antibodies that morning.

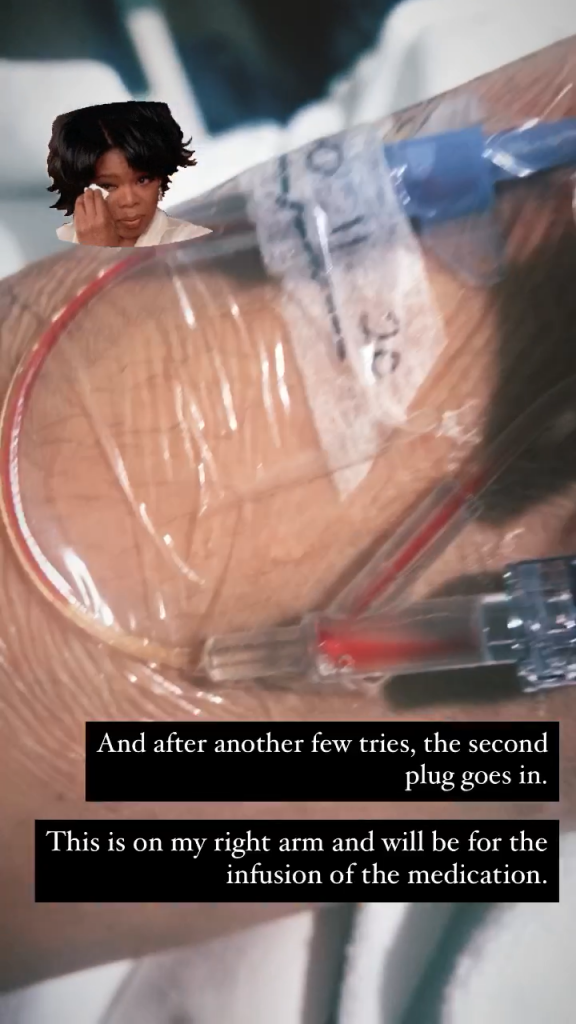

The first wave of attacks began at 5 AM. At first I was like, “Could they insert the tube into me while I’m still sleeping later, since I’m all strung up with IV plugs and can’t move anyway?’

But, as it turns out, they couldn’t even insert the IV plugs for 45 minutes because I was so hungry that I was shivering in bed. My veins were shrivelled up and hiding. They had to wrap me in four blankets like a popiah and wait patiently for me to defrost.

So we were practically in bed for the whole second day, having our blood drawn at regular intervals. We were drying up.

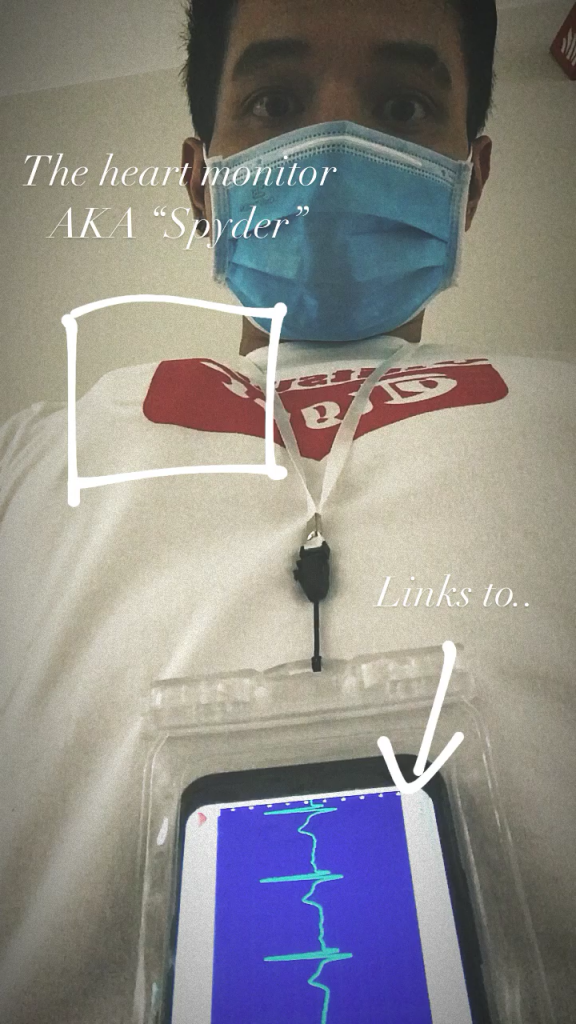

Other than that, they needed other vitals like, ECG, blood pressure, temperature, urine sampling … That was our real contribution to the whole experience.

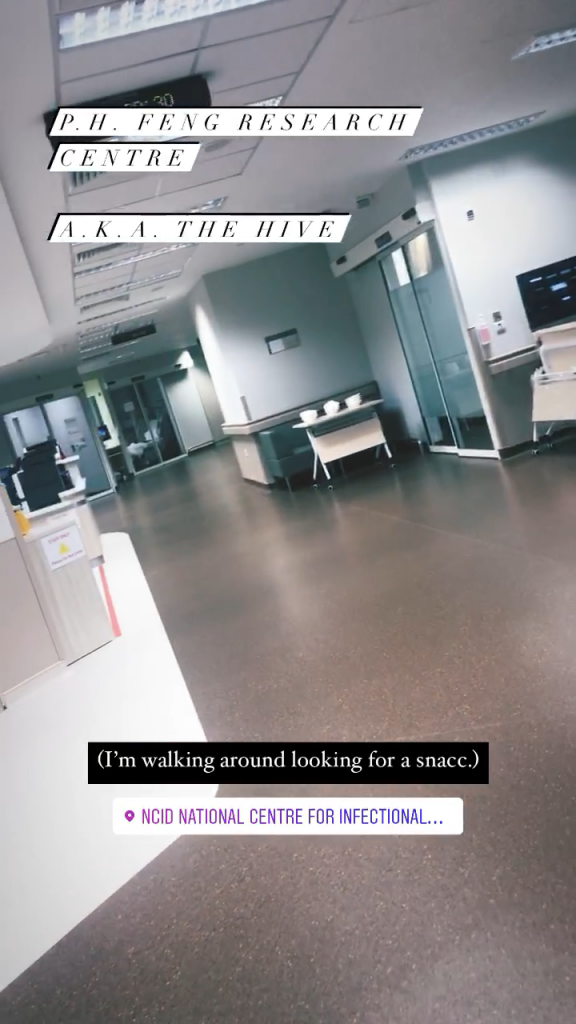

But after the second day, I could get up and start disturbing—I mean, making friends with people, especially the staff. I would amble around, explore the place, talk to the nurses … I realised that they were actually very caring and adaptable. As long as we were well behaved. (For the most part, I was a model inmate. Except maybe when I was aggressively trying to make them shoot TikToks with me.)

For example, when they saw how badly the lack of food affected us, they went to get approval to bring us snacks. And the food eventually got better.

They also helped me discreetly with my roommate. He was an awesome guy and his snoring was equally awe-inspiring. By that I mean awful. I ended up sleeping at 3 or 4 AM most nights, which is not tragic because I normally sleep at that time or later, but I had to wake up at 8 AM daily during the study, or risk a cold breakfast.

So someone got ear plugs for me. They also prepared a separate room for me so I could sneak there to sleep if it really gets too noisy.

On the second last day, it was the birthday of my non-snoring wardmate. We had a little … I want to say party, but it wasn’t really one, because it was not allowed. Nonetheless, the staff bought a cake and we sang the birthday song—in three different rooms because we couldn’t be close together.

We later found out that the staff had been planning the celebration for two days, and for the cake-cutting to take place during their shift change so most people could be there. They really helped us to bond as prisoners.

Obviously, they couldn’t organise any activities for us. They did, however, provide us with tools to entertain ourselves. There was a TV, Netflix, WiFi, a pantry with food, a dartboard, and foosball table …

But for the most part we didn’t really feel like we had the energy to do anything even mildly exciting. None of us played the foosball because, oh my god, have to stand up for so long?! All of us found ways to amuse ourselves that didn’t require moving. A lot of watching of shows and stuff like that.

During the study, my roommate was still working. With a mixture of annual leave and working from home, he could actually complete his work at night in the pantry.

I just ended up playing a lot of DOTA on my laptop. I had online Netflix parties with my friends outside the study as well. There was one day when I started watching The Exorcist at 1 AM, with all the lights off. I quietly left my jail cell carrying my laptop, shuffled to the pantry and sat down in the darkness. The nurses, suspicious but also creeped out, were like, “Are you ok?!”

I reckon that they were worried for my declining sanity.

But of course, since we were doing this for medical science, there were a lot of limitations to just how comfortable the experience could be.

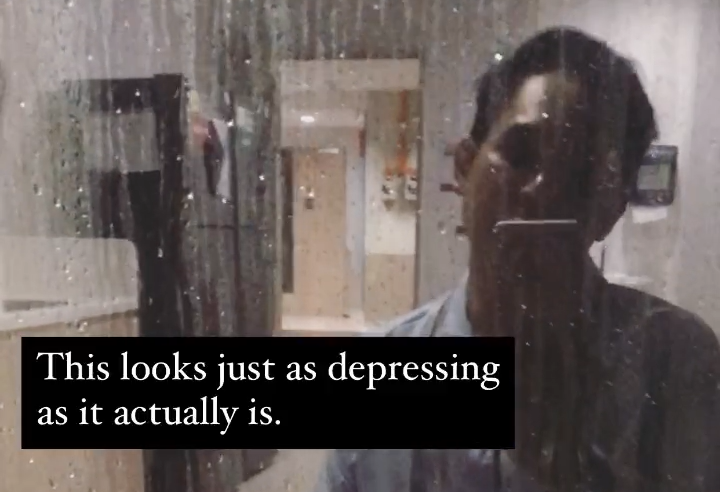

For normal medical trials, they have a visitor room. But because this is Covid related, we were cloistered away completely from other humans. We never saw the sun for a week. If the study had gone on longer for a week, I might have grown melancholic and in fact, colic.

As good as the experience and quality of care was, not being able to do something simple as taking a walk in the sun for some vitamin D, to breathe some air, can be mildly depressing and physically stressful.

The study doesn’t end with the trial, however. There is still a 3-month follow-up window when I have to return to NCID to have my vitals tested. For that, they’ll still give me some honorarium and transport allowance. In total, through the course for the whole study, each of us will be compensated fairly handsomely, about what an average Singaporean would earn in a month.

However, you must remember that they have zero data on the side effects of the antibody. Because Covid struck us so suddenly, they haven’t even had enough time to assess the long-term side effects on animals. I’m the 4th human to have the antibody. I’m almost Project Alice.

6 months later, you should check if I’m still alive.

Laughter.

Right now, I haven’t experienced any side effects. Beyond lots of bruising and losing weight.

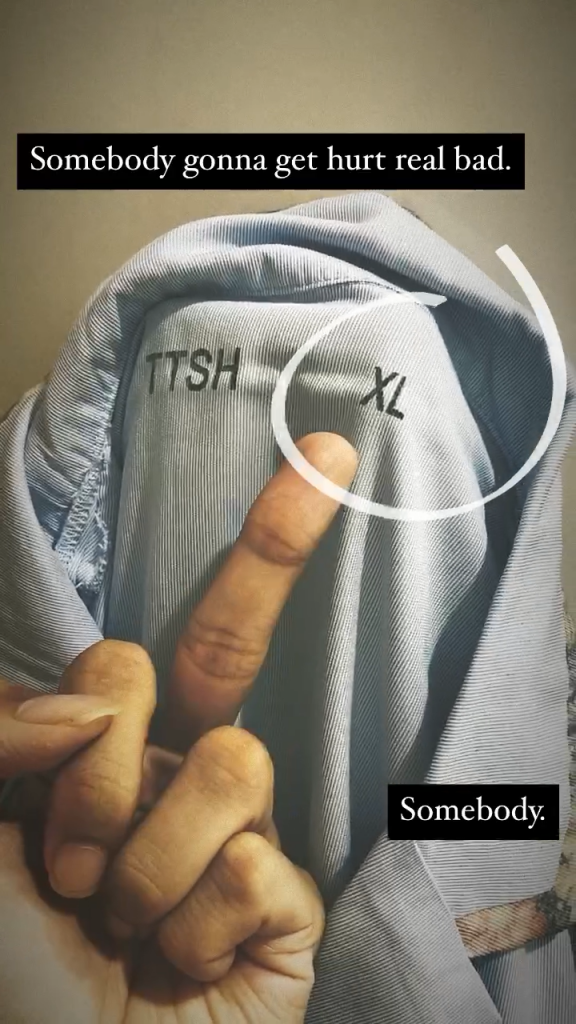

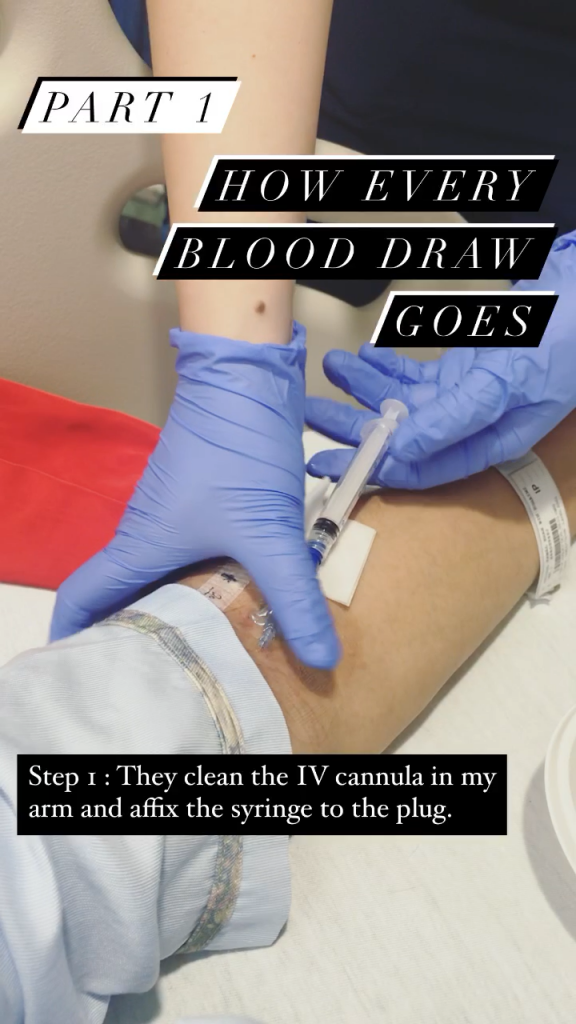

The only lasting physical evidence of the study are the bruises and marks where IV plugs were, because the plugs were there the whole time, day and night, on each arm. The plugs are basically … USB plugs. A universal, open hole into which a nurse can insert things with the appropriate USB head, whether it’s to inject the antibodies or draw blood.

The low-salt, low-fat diet that they imposed on us has stuck with me, actually. Because of the daily blood work, the doctors made the incidental finding that I have high cholesterol and some liver damage, and I’ve become more cognisant of what I eat.

Just last weekend, I was shopping for snacks with my friends, this unexpected exchange happened:

I said, “Let’s buy fruit.”

They asked, “Why such a Debbie downer?”

I replied, “Hello, I might die of high cholesterol.”

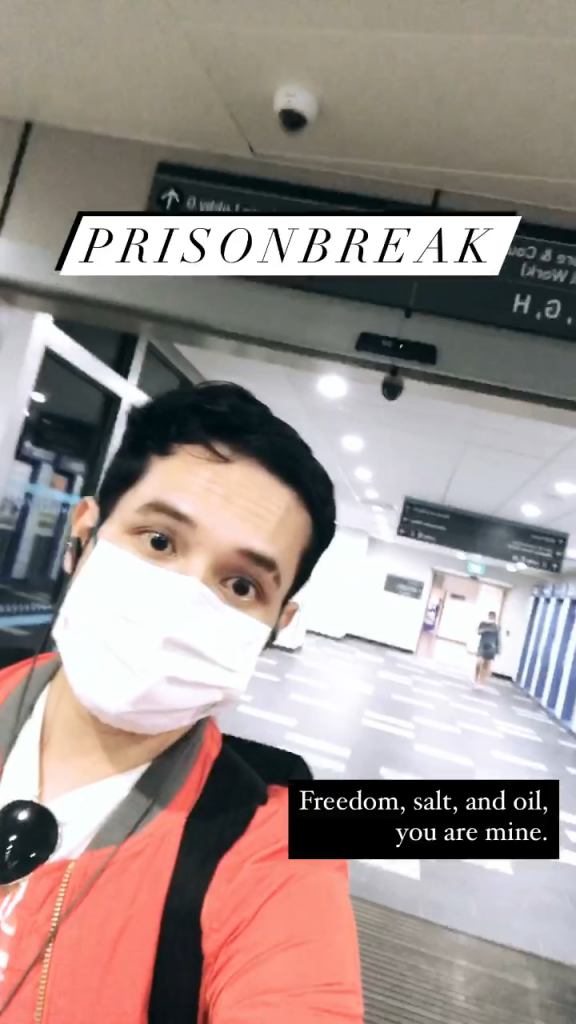

I find healthy food less intolerable now. But I have to qualify that because among the first things I did after I got discharged was to have lunch at Curious Palette. It started with a whole bowl of truffle fries. By myself. I needed salt.

For my main course, I had mentaiko pasta. I needed umami.

And Shake Shack after that.

Then steak for dinner.

That was the first day after my study. I was making up for the lack of food during my imprisonment. In other words, the main thing going through my head after my release was: ORD loh!

This is a good reflection of where we are as a society, in terms of how far we’ve gotten along in our fight of Covid. It’s a matter of public health and concern, not individual risk-taking. I think any other person in my situation would also feel the same way—no one would feel any less obligated to do all those things any Singaporean would do for the sake of each other.

That whole experience has made me feel differently about what it means to contribute to resolving the public health crisis. It feels nice to say I’m doing something, helping in some way, however small, during a pandemic when we feel so helpless.

Although I’m being compensated for my time, it made me think about what other ways in which ordinary people who do not necessarily have a frontline role, can contribute and be more essential than we actually are.