For the past week or so, you’ve probably been reading about struggling F&B operators (aka “merchant-partners”) highlighting the “high” commission fees charged by food delivery app platforms like GrabFood, Foodpanda, and Deliveroo.

In this pandemic, where dine-ins are no longer allowed, restaurants have become reliant on food deliveries and takeaways. Which means food delivery apps are now essential services.

While the three app platforms have been charging F&B operators roughly 25-30% commission fees for every meal delivered before Covid-19, the fees have become a source of debate—especially since they consume one-quarter to one-third of daily takings.

Delivery app providers have explained that the commission fees are necessary to pay additional earnings and incentives to their delivery riders. On top of this, customers have become used to seeing a S$3+ delivery fee in their orders, not realising that the real cost of delivery is actually much higher.

So on one hand, you’ve got F&B operators pining for lower commissions from delivery app providers. On the other, delivery app providers need these commissions to pay their riders and cover their overheads. It’s one hell of a Catch-22.

This begs some questions: is the commission rate necessary, especially during this pandemic? If it is, are the F&B operators the only ones suffering? What about riders (aka “delivery-partners”)?

To find the source of the issue, and understand whether there are alternatives to fix this entire mess, we need to consider different viewpoints.

App Platform Providers

Grab told RICE that in Singapore, the average order value is around S$15-20, so the 25-30% commission works to around S$3.75-S$6 per order.

I’ve verified this by looking at delivery invoices from all three providers, based on a typical S$18-20 meal. On a per-delivery average, that F&B outlet was being charged about S$6 by Deliveroo, S$5 by Foodpanda, and S$5-6 by GrabFood.

“Any new changes to be introduced in favour to one party is not to be taken lightly as it will inevitably affect the other three parties (customers, merchants, delivery-partners) in the ecosystem,” Grab said, and there’s actually some truth here.

This is further illustrated on Grab’s social media and blog.

So, instead of lowering fees, Grab is accelerating on-boarding times for new merchants, waiving commission fees for self pick-ups during the CB, paying merchants daily, and marketing a “Local Heroes” promo for smaller F&B outlets.

This is all well and good, but since commission fees for deliveries are the issue, the question we should also ask is: are said commission fees being used to compensate delivery-partners fairly? Are they happy with the compensation system? (More on this later).

Likewise, Deliveroo is waiving its S$650 registration fee and paying merchant-partners weekly now.

Of course, some of us finance-savvy folks might ask: aren’t these app platforms making enough money to incentivise their riders out-of-pocket? After all, based on the double- to triple-digit hyper-growth numbers reported on Grab, FoodPanda, and Deliveroo last year, they really should be able to.

While I can’t say for sure if these instances of hyper-growth (revenue? customers? ridership? merchants? all of the above?) have been able to off-set other money-losing aspects of these privatised businesses (which I’m not privy to), it now shines a spotlight on the business model.

We saw what happened to Uber and UberEats, and we know how they gave a chunk of their revenue to incentivise delivery-partners, and offer discounts and promotions to gain market share.

Food & Beverage Operators (Merchant-Partners)

One F&B operator who’s been in the limelight is Anthony Yeoh, chef-owner of Summer Hill. He took his restaurant completely off Grab and moved to Lalamove. For online ordering and island-wide delivery, he’s considering Oddle, which takes a 10% cut for every deal.

“In a time of crisis, having a cash flow to pay for the costs of pivoting a business is important. We can’t do that when 30-40% of your gross is going out the door to delivery platforms. It leaves no margin for error in a crisis, which is unrealistic,” he shared.

“What saddens me is the three main food delivery platforms are in the best position to help. Stop with canned answers like “this is the minimum commission we will go to”, “we provide marketing support” or “free photos”. Address the fact that in this crisis, the system is not holding up. Let’s fix it together before people and their businesses shut down.”

In recent weeks, the #SaveFnBSG group has been mobilising the F&B industry to rally and push for lower commission fees. It cited San Francisco as an example, where fees are capped at 15%, reflecting how most F&B operators want lower comms, at least during the CB period.

It’s too soon to tell if they work better or provide better margins in the long run. Don’t forget, there’s a human cost to running any delivery system, which I’ll get to later.

Cedric Tang, 3rd generation owner of the “Ka-Soh” brand of restaurants and Swee Kee Eating House, gave up on the three platforms and decided to do island-wide delivery through his own in-house ordering platform, which he designed with his brother.

“Our costs go to paying third-party logistics providers and taxi drivers who help us deliver the food—shared between customers and us. It keeps two of my restaurants afloat and I still need to earn enough profits to cover our Amoy’s branch rental, even though we’re closed during the CB period.”

Howard Lo, who runs Tanuki Raw, Salmon Samurai and Standing Sushi Bar, still uses all three delivery apps but also built his own delivery service.

With deliveries at S$13-28 per trip, he relies on batched orders to average out his costs. He pivoted a number of his staff to become delivery coordinators, utilising contract riders dedicated to his outlets to supplement courier services from Lalamove and Carpal.

“Delivery logistics are incredibly time-consuming, so I can understand the advantage of app platforms like Deliveroo, Foodpanda, etc. as these guys take care of coordination and scheduling of riders.”

Drivers and Riders (Delivery-Partners)

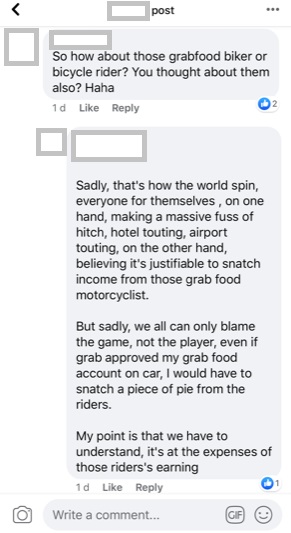

If commission fees are the monetary issue at hand, delivery-partners are the human face of it, and their only source of income is via delivery apps.

What’s worse: their competition has increased, so everyone’s wrangling for the same pie pizza.

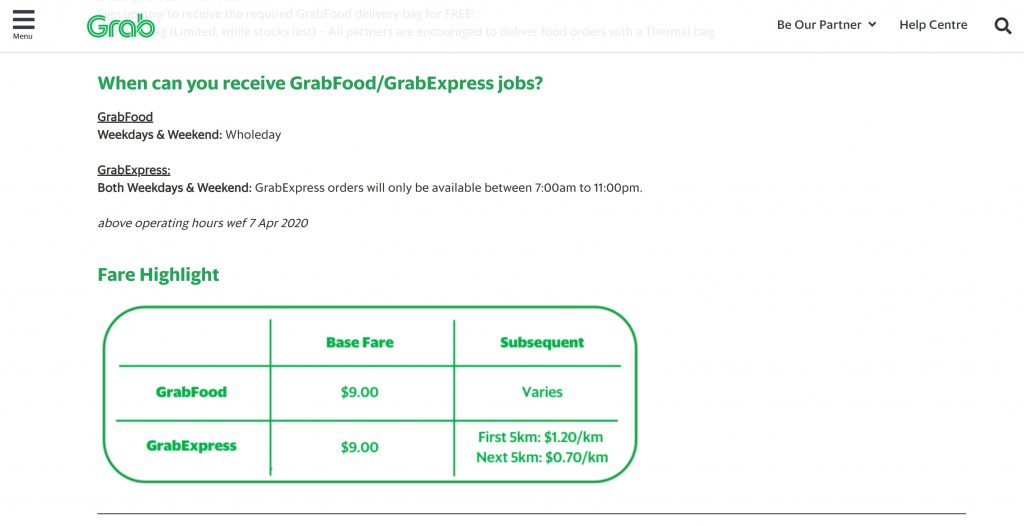

Grab opened its GrabFood/GrabExpress food delivery programme to thousands of PHV GrabCar drivers in end-March. Deliveroo is adding 2,000 more riders to its current 7,000. Foodpanda tied-up with ComfortDelgro to allow taxi drivers to deliver food.

Just this month, Enterprise SG onboarded partners like Lalamove and Zeek to the delivery pool, and is funding 20% of their delivery costs. ESG has already introduced a 5% commission relief to the three delivery platforms (to pass on to operators).

Kai (not his real name), a delivery rider for GrabFood and Deliveroo for 1.5 years, has kept his criticisms mostly to himself … until recently.

A divorced father of a ten-year-old son, he lives with his parents and has been using his bicycle, PMD (before the ban), and a power-assisted bike for his deliveries.

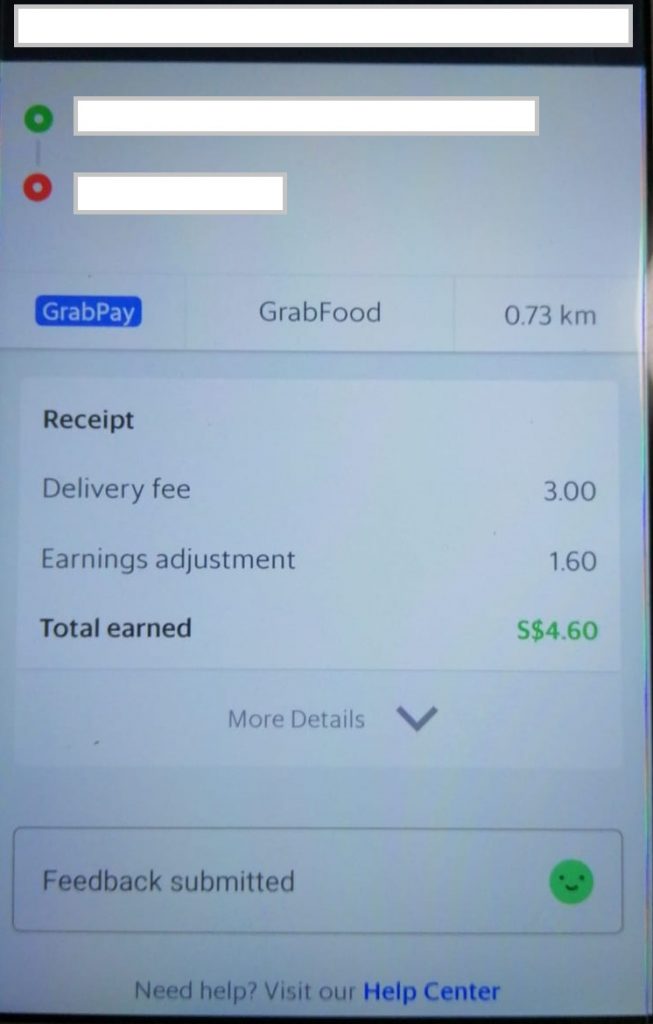

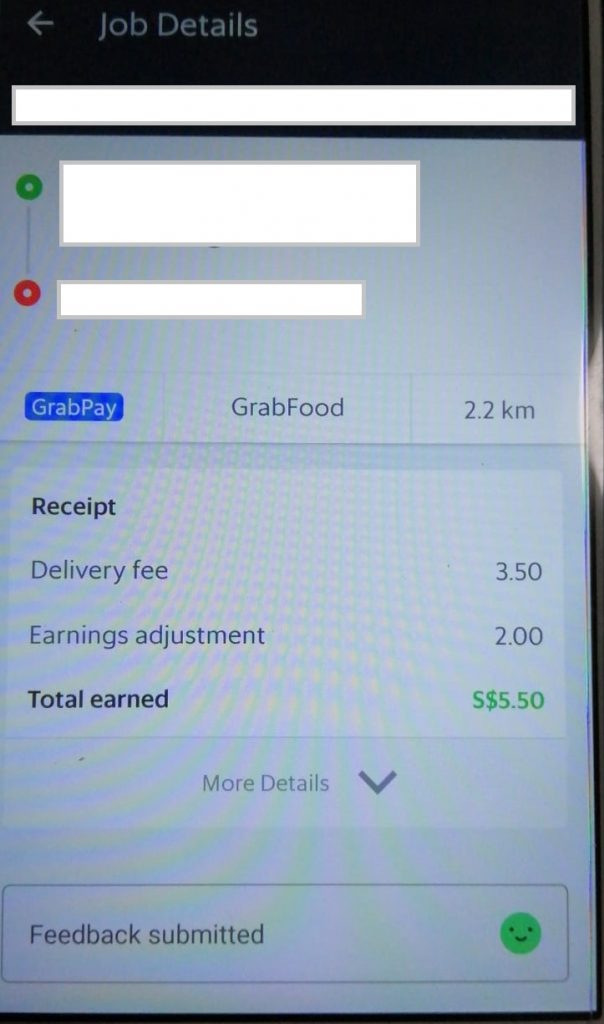

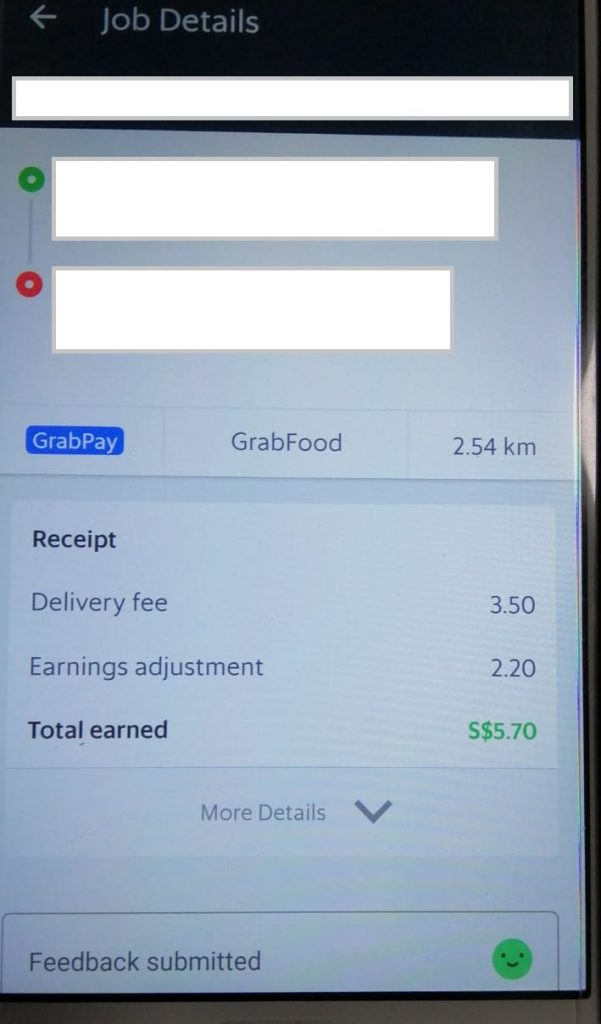

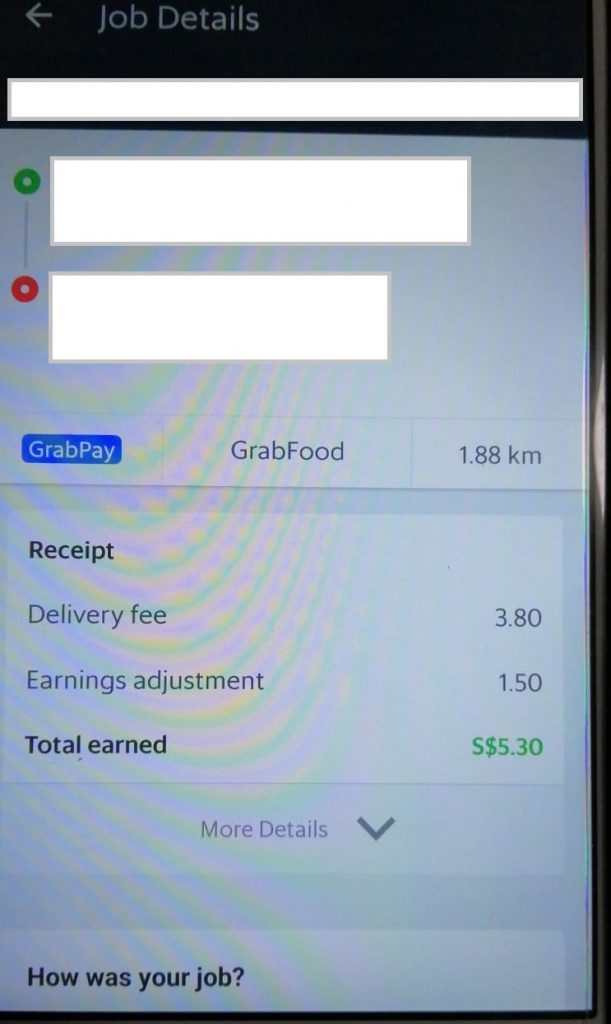

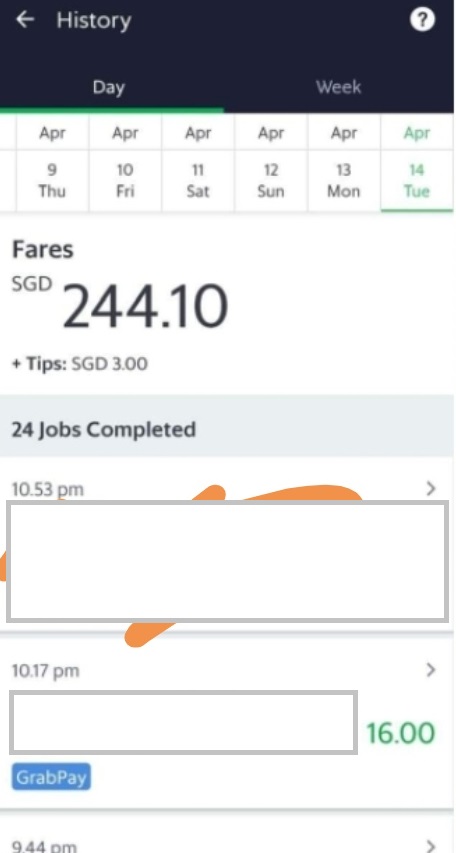

“Before Covid-19, I used to take home an average of S$80-100 a day. Now, it’s S$40-50 for 6-8 deliveries a day.” EK, another GrabFood delivery man, makes about S$70 with 13-14 orders a day.

“Bubble tea shops and McDonald’s are our most common delivery orders in the first two weeks of CB. With their closures, I honestly feel worried if I’ll get any orders,” he said. (At the time of publication, McDonald’s and most bubble tea shops have since closed.)

But, with the pandemic, Kai sees it differently: “F&B kitchens are short-staffed now, so each job we deliver now takes 45 minutes. Which means we need to do more jobs to get the same incentive.”

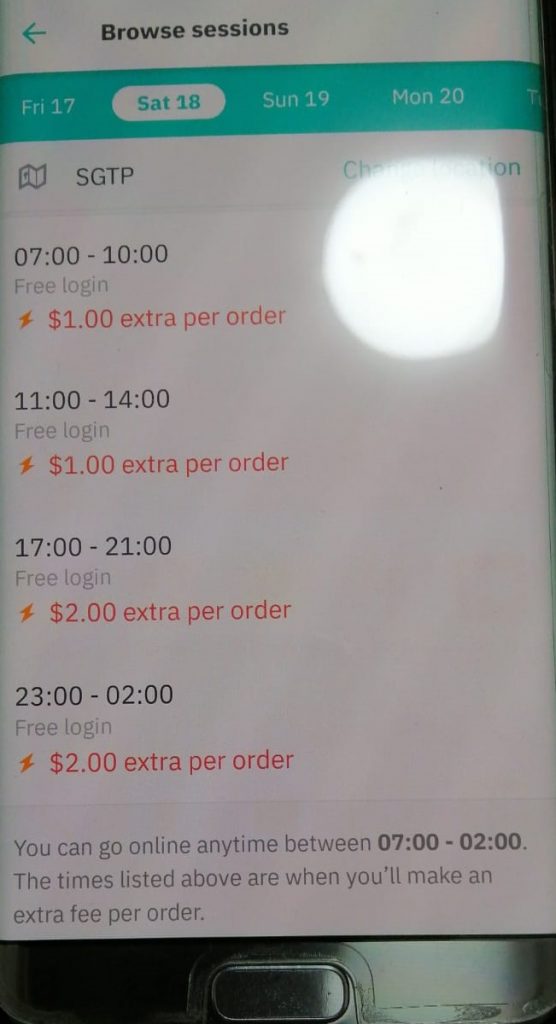

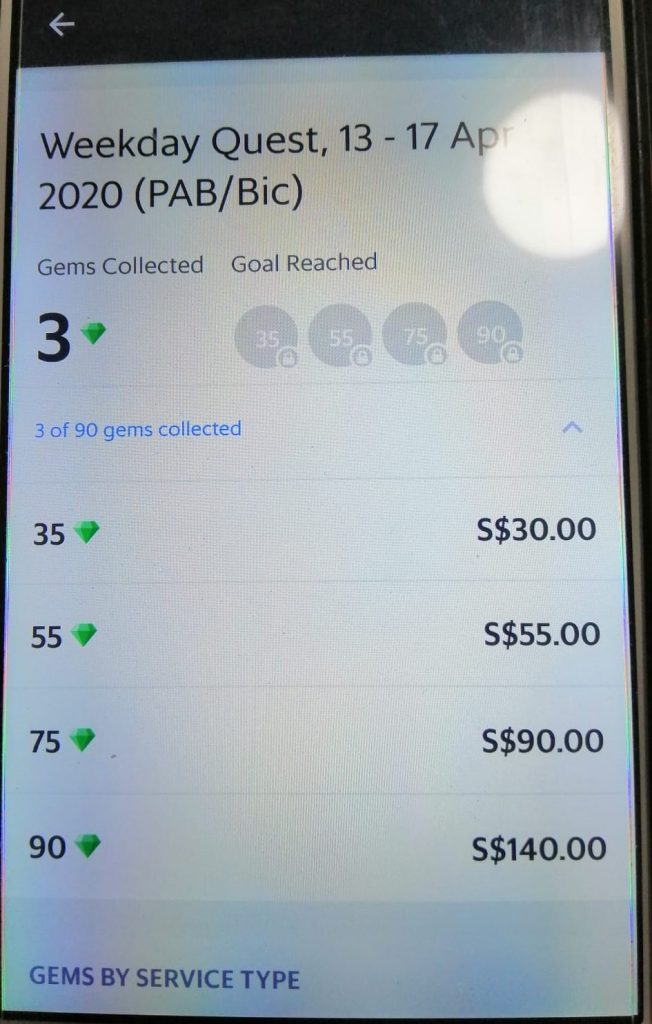

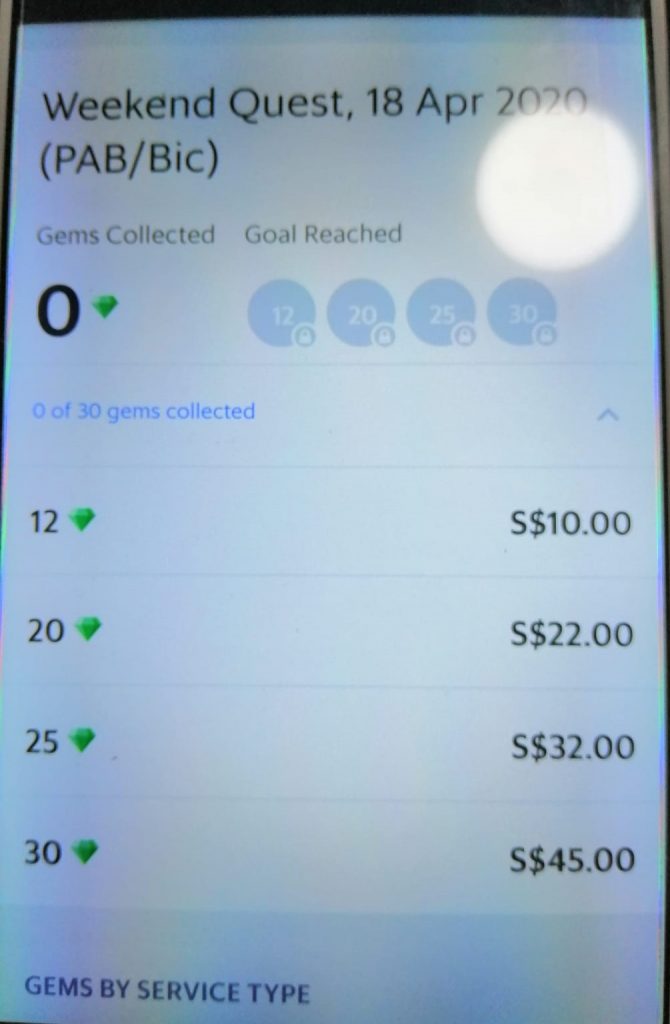

To earn incentives, a rider must fulfil a number of jobs and maintain an acceptance and cancellation record (AR/CR). It used to be 8:2 AR/CR, but now, it’s 9:1. This means for every 10 jobs, he can only cancel 1, or he’ll miss the incentive.

Riders in the business know that cancellations are reserved for notorious restaurants with long waiting times or situated in super ulu places. If they’re hit with a few, game over man.

They’ll end up delivering food late or cold and get a bad rating from an irate customer. The system assigns them less jobs and hence, lesser income.

“It’s a sucky feeling to know your livelihood is controlled by an algorithm,” Kai says.

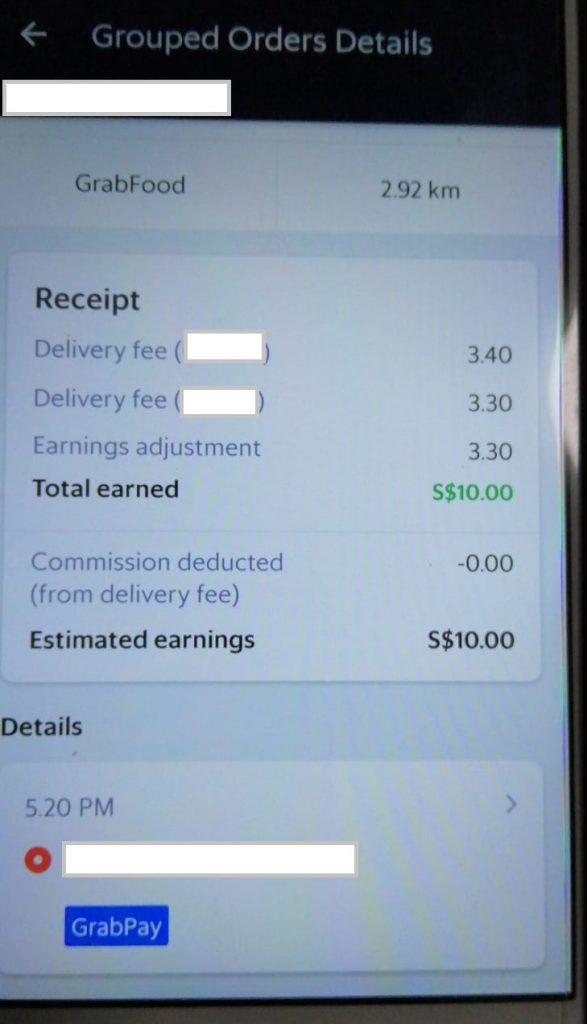

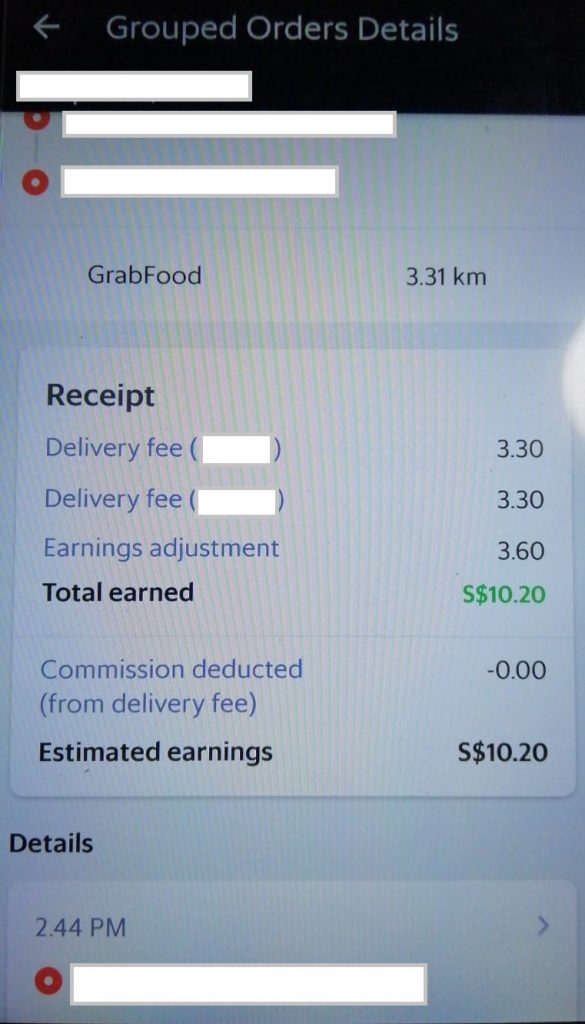

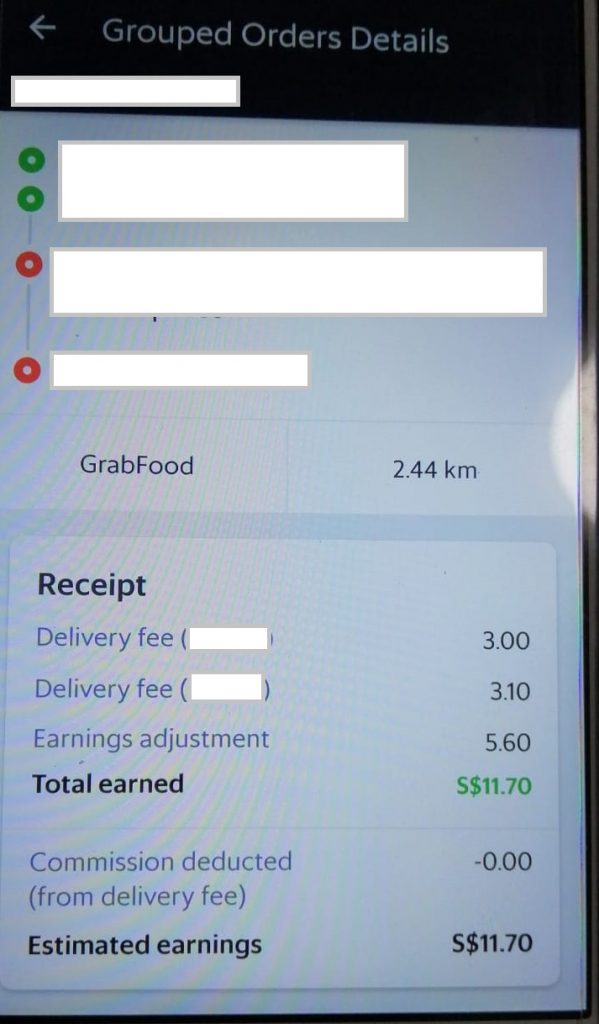

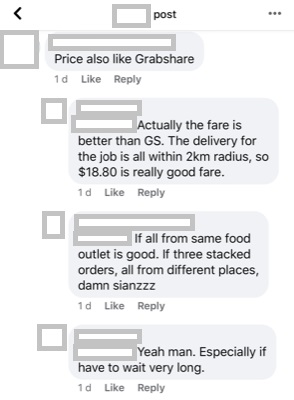

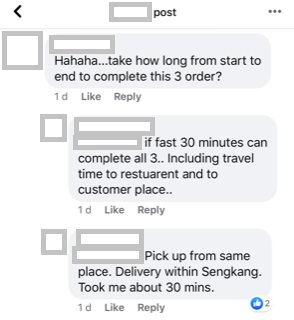

Grouped orders are jobs from one restaurant to multiple locations. They reduce back-and-forth delivery turnarounds, and aggregate jobs for the rider. Good for the rider, right?

Wrong.

Grouped orders actually cost-average lower compared to individual delivery orders.

“Recently, we’re getting more grouped orders, and not all from the same restaurant. Instead of getting S$5.50 per job, we’re now paid S$9.30-S$9.50 for two grouped jobs. Many of us are accepting just 1 order at a time and then shutting the app off before a 2nd order comes in.”

It potentially means the system’s cost-averaging down on payouts.

But it’s not a sure thing either. Ultimately, it’s up to the “algorithm” to determine distance and whether there’s enough personnel near the outlet to accept the order.

In response to our query, Grab’s spokesperson said, “Leveraging our data analytics system, we are making real-time adjustments to make sure all delivery-partners are assigned jobs that optimise the respective types of vehicles they deliver food on. This helps them to deliver the food orders in the most efficient manner and maximise their earnings.”

This pandemic has revealed that despite increased demand, the commission-and-compensation structure of food delivery apps isn’t exactly making F&B operators and delivery riders happy.

Both parties have to work doubly hard while earning less compared to pre-Covid-19 times. The bigger question is, if F&B operators want lower commission fees, and delivery-partners want fairer pay, are consumers willing to foot the top-ups and incentives?

“As a customer, if I’m stuck at home for 30 days with a family and I order 2 meals a day, and I’m paying say, S$10 per delivery, that’s S$600. That’s daunting. Customers have been conditioned to see S$3 as a delivery charge from Deliveroo, Foodpanda and Grab. They don’t realise how much the true delivery cost is, especially for island-wide delivery,” Tanuki Raw’s Lo said.

Lo brought up a good point. If consumers are unable/unwilling to cook at home, or take a walk or drive to dabao, should they not bear the additional delivery costs? It’s a fair consideration, at least to sustain both parties through this pandemic.

This means that delivery app platforms will have to pass portions of that 30% commission fee to consumers. Bear in mind, food delivery was never meant to be for daily use, or to sustain a restaurant, so maybe call it a Covid-19 service fee? At least until the CB lifts.

But one thing’s for sure: whether this happens or not, the landscape’s already changing. Many F&B operators have since developed their own online ordering and delivery systems.

Ka-Soh’s Tang is already seeing the benefits. “Recently, we’ve been tweaking our minimum order and looking at delivery charges—how much should we charge the customer versus how much do we pay our delivery partners.”

Smaller and perhaps less tech-savvy merchants, like Ritz Kitchen, are staying put with existing app platforms. They’re reliant on GrabFood’s Island-wide Delivery service, which has helped them increase orders by five times. There’s nearly 800 merchants on the service.

“We are a humble eatery in Jurong. GrabFood is now the main channel for us to reach customers. Response has been overwhelming,” said Lawrence Low, Ritz Kitchen’s director.

While the ecosystem’s still in flux, Summer Hill’s Yeoh feels the best solution right now is for delivery app providers to engage all stakeholders—restaurants/merchants and riders. A sustainable structure of commissions and incentives needs to be established so that everyone is incentivised to support each other.

This is similarly echoed by delivery-partners, who need more support from platform providers more than ever now.

“In the food delivery app ecosystem, we, the ones using bicycles, PABs or walking, are at the mercy of the platforms’ algorithms,” Kai said.

“Take what happened on April 21,” EK said, “when bubble tea shops everywhere were forced to close by midnight. Delivery riders like me had to jostle with other riders under social distancing rules, while waiting for our orders to be ready—just because Singaporeans panic-ordered bubble tea at the last minute.”

That night, EK couldn’t call Grab customer service to cancel his order. If he did it on his app, it would mean getting a bad record. He was stuck there for hours and left empty-handed.

The issue over commission fees has opened the eyes of different players in the ecosystem. Several F&B operators now run hybrid delivery ops, more may venture out to do the same soon.

With more competition now, delivery riders might bail, preferring to go freelance with F&B operators, negotiate, and earn fees on their own terms.

For the rest of us at home, the advice during this CB period is still to take away directly from the F&B outlet. It’s on every F&B operator’s wishlist and you can find listings on social media.

If you choose food delivery instead, decide if you’re willing to foot the additional delivery charges just for this period and don’t forget to tip the rider.

Trust me, the last thing we need right now is for an algorithm to tell us what to do.