“I swear, we literally snort that shit by the bucket.”

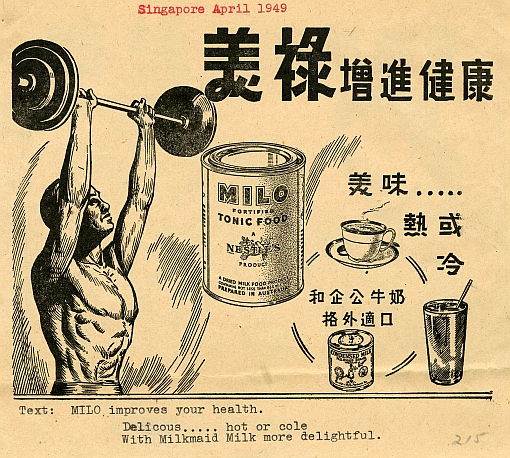

However, what you might not know about Milo is the historical link to Tuberculosis and public health. In the late 1950s, Milo was not an accompaniment to your maggi goreng or three-piece chicken meal. It was used to boost children’s resistance to TB.

Since a well-fed child of healthy weight and adequate protein intake is ‘less likely’ to get TB, skimmed milk was given to young children at school. During recess, teachers would pick out the scrawniest, most malnourished-looking kids and give them The Milk Cure.

The good news: it was free. The bad news: everyone hated it because the milk had an ‘unpleasant odor’.

Was this the origin of Singapore’s Milo fetish? Did their love for malted beverages endure? What if the principals had chosen Horlicks instead? Would we all be changing our McDelivery orders to Ice Horlicks?

These are the burning questions which keep me awake at night. Dr. Loh Kah Seng/Prof Li Yang Hsu’s new book Tuberculosis: The Singapore Experience, 1867-2018, does not answer these questions, but the book does offer up more thought-provoking perspectives about TB, Singapore, and Singapore’s tortuous relationship with infectious disease.

It is a pertinent—if somewhat depressing—read in the midst of our current Coronavirus outbreak. The book is a chronicle of how far we’ve come since the 1800s, but also a story about how little certain things have changed.

Since most Tuberculosis sufferers were male Chinese migrants living in the overcrowded shophouses, TB quickly became a ‘Chinese Disease’.

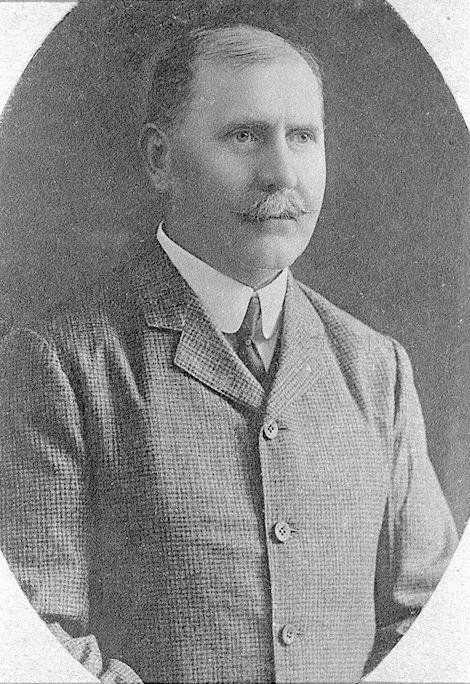

This would be understandable, had it not turned into a libel of Chinese people in general. In 1907, Sir David Galloway—personal doctor to the Sultan of Johor and founder of the Straits Medical Association—wrote that “The Chinaman is the most insanitary of mortals”. Cities in China were “instances of filth” and Chinese migrants in Singapore—unlike the European populace—did not cooperate with the sanitary authorities because they lacked intelligence.

He was not alone. Such views were not just widespread, but orthodox. The Chinaman, although filthy, was said to have a ‘natural resistance’ to TB. Straits Chinese—i.e. Peranakans—caught TB because of their ‘immoral behaviour’.

Portugesese and Eurasians were also uniquely afflicted with TB, although they were not considered filthy.

Even the architecture became racialised. Asian peoples, in general, were said to ‘dislike air in their dwelling-house’. Since the cause of TB’s spread was blamed on ‘dark’ shophouses, British medical expert W.J.R Simpson concluded that: “The Chinese prefer, where possible, to build horizontally, rather than vertically.”

Malays were considered the most susceptible, followed by the Japanese, the ‘agrarian’ Chinese, and “some Indian races, most notably Sikhs”. More often than not, these ideas were confusing and self-contradictory. China-born Chinese were said to possess a ‘wonderful degree of resistance’ even though large numbers of coolies ‘invariably died’ when they got TB.

The disease was said to be ‘wonderfully rare’ amongst the Malay population, even though they were the ‘most vulnerable’ to it. Sir Galloway attributes it to ‘the phase of civilisation’. The less developed, the more vulnerable to infection.

Multiple attempts were made to build a sanatorium for TB patients, but each time it failed because of nimby-ism.

Plans for a Pasir Panjang hospital fell through because upper-class citizens did not want to live next to a TB ward, even if it had fences.

Another proposal to site it in Seletar’s Trafalgar rubber estate was likewise scrapped because of complaints from a wealthy landowner named Tan Soon Bin, who suggested that TB would spread by patients defecating or urinating near the seaside.

As it turns out, moral panic about the slums and migrant labour did not translate into any meaningful policy. The racial theories of disease had a useful side effect: as an excuse for the government to shrug their shoulders and go, “C’est la vie.”

After all, if TB was a ‘Chinese disease’, it was perfectly acceptable to do nothing. The government could not be asked to resolve deep-seated racial/cultural problems. Just as racial ideas about TB freed British-South African mining companies from the responsibility of keeping their workforce healthy, the spectre of ‘The Filthy Chinaman’ placed the blame on Singapore’s coolies, instead of the colonial authorities.

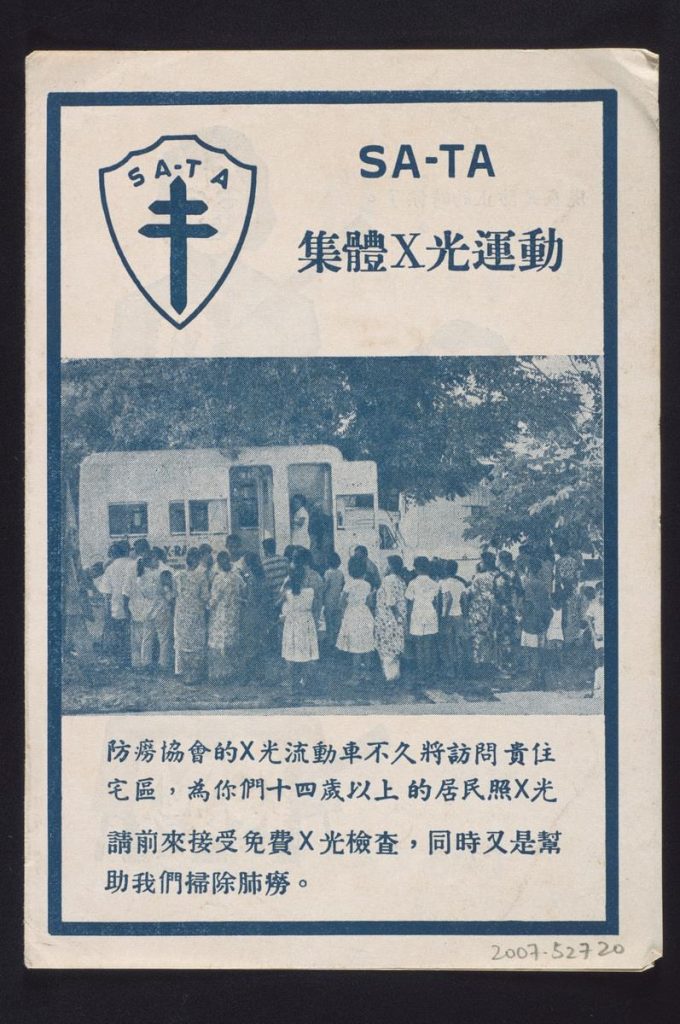

There is no clear-cut, single reason for why TB waned. Instead, there was a smorgasbord of different policies. Milo was one (ameliorative) solution. Contact-tracing, better healthcare processes, outpatient treatment, public education, and X-rays were just a few others.

I don’t want to sound like a social studies textbook, but to give credit where credit was due: the newly-elected PAP government did not lack for will when it came to disease eradication. Aided by NGOs like Singapore Anti-Tuberculosis Association, they carried out mass X-ray screenings where every citizen had their lungs examined for signs of TB. Primary School children were tested and given the BCG vaccine.

There was even an anti-spitting campaign which stigmatised spitters as “stupid, selfish and lacking in education”. Chinese storytellers were deployed to spread the cautionary tale of one Uncle Ho, an indiscriminate spitter who killed his entire village by launching TB-ridden phlegm in every direction (Netflix series forthcoming).

But perhaps the most surprising of all anti-TB efforts was the HDB. Even though public housing was not created as a solution to Tuberculosis, it was regarded as a key factor for why cases declined after independence. With people no longer cramped into ‘airless’ shophouses or unregistered ‘cubicles’ which made contact-tracing a nightmare, it became easier to monitor and to control the disease’s spread.

The Ministry Of Health concluded that “Perhaps more than any other non-specific measure, this has played a key role in the reduction of Tuberculosis in Singapore”. More than 50 years after slum-like housing was identified—vilified—for causing epidemics, Singaporean finally began moving out of the ‘terrible slums’ with their ‘dark dank cubicles’.

But what can we learn from the disease’s history? What lessons can be drawn in aid of the fight against Covid-19? This is probably what you’re thinking, but the answer is not so simple, and Tuberculosis: The Singapore Experience offers no easy insights or clear-cut solutions, except one.

Racial classifications of disease are, more often than not, pretty useless. Chinese coolies were the most susceptible to TB, but they were equally susceptible to typhoid, cholera, and beri-beri because there was no cure for an empty bank account, which leaves you vulnerable to nearly everything.

Hence, the authors of the book conclude: “the illness affected particularly low-income workers residing in congested housing, suffering from poor health.”

There are no more migrant workers in Chinatown’s shophouses anymore. It’s all yoga studios and overfunded start-ups. However, most of the migrant labour upon which Singapore’s prosperity depends still reside in relatively congested housing—dormitories, cheap hostels—rooms that make HDB flats look like good-class bungalows.

However, migrant workers do not get free face masks from the government. They also do not have the luxury of working from home, unlike DBS employees. One of them is already in critical condition, and others are reportedly protecting himself with bandanas. NGOs like itsrainingraincoats are collecting masks and vitamin C for migrant workers, but they can’t do it alone. There are too many workers, and not enough activists.

Perhaps the next logical step is for our government to distribute free masks and disinfectant to those who are most vulnerable and least able to afford protection—our migrant workers. The early history of Tuberculosis in Singapore is a history of incompetence mixed with indifference, but the history of the Coronavirus need not be the same.