The school didn’t dismiss Rebecca, but neither did it offer a solution. It simply recommended that she let her child access Student Learning Space (SLS) via her smartphone.

But SLS didn’t work on her smartphone, perhaps because it was on an old operating system, or because the hardware couldn’t support it.

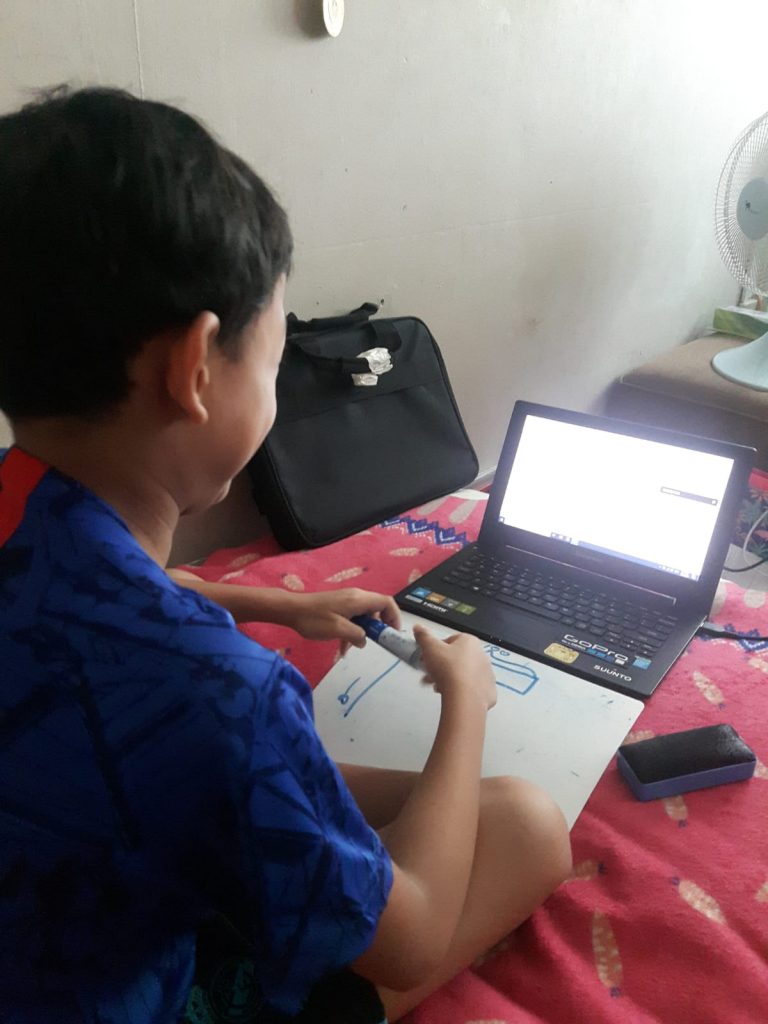

Panicking that her child would be left behind in their studies, Rebecca reached out to community organisations and self-organised groups of parents. Eventually, she stumbled upon Engineering Good, a local non-profit organisation that was refurbishing donated laptops and distributing them to needy families for HBL.

Here, she thought, she could finally get the help that families like hers needed.

Would Engineering Good happen to have eight spare laptops?

SCFSC was in contact with families who lived in 1- to 2-room rental flats around Redhill, many of whom struggle to afford basic necessities, let alone laptops, and were worried their children would not be able to do HBL.

Within two days of that request, Engineering Good—with the typical efficiency of engineers—activated its network of volunteers, solicited donations, refurbished laptops, and sent them off to these families.

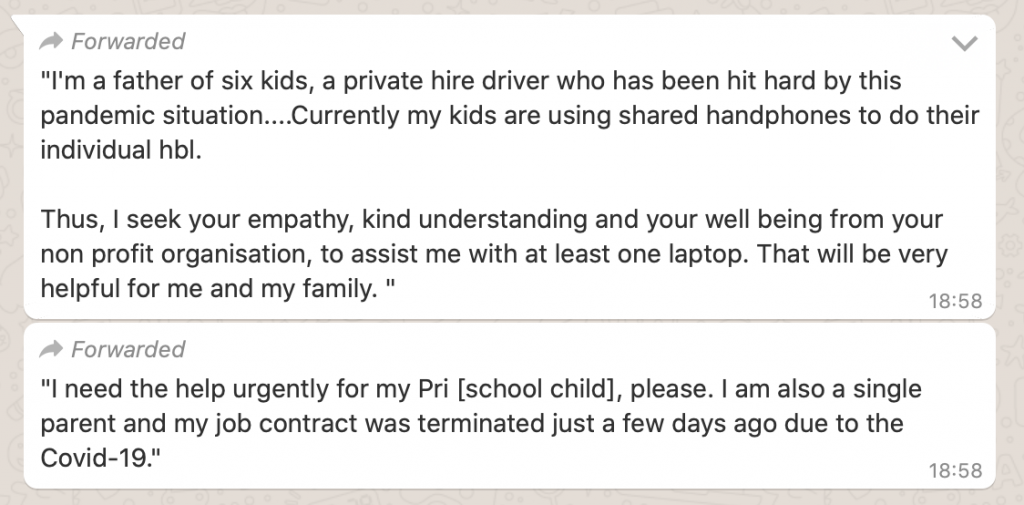

That was supposed to be it. But word got out that a group was refurbishing donated laptops and distributing them to underprivileged children who needed them for HBL. Engineering Good’s Facebook page, which receives around two messages yearly, was suddenly flooded by pleas from needy families like Rebecca’s.

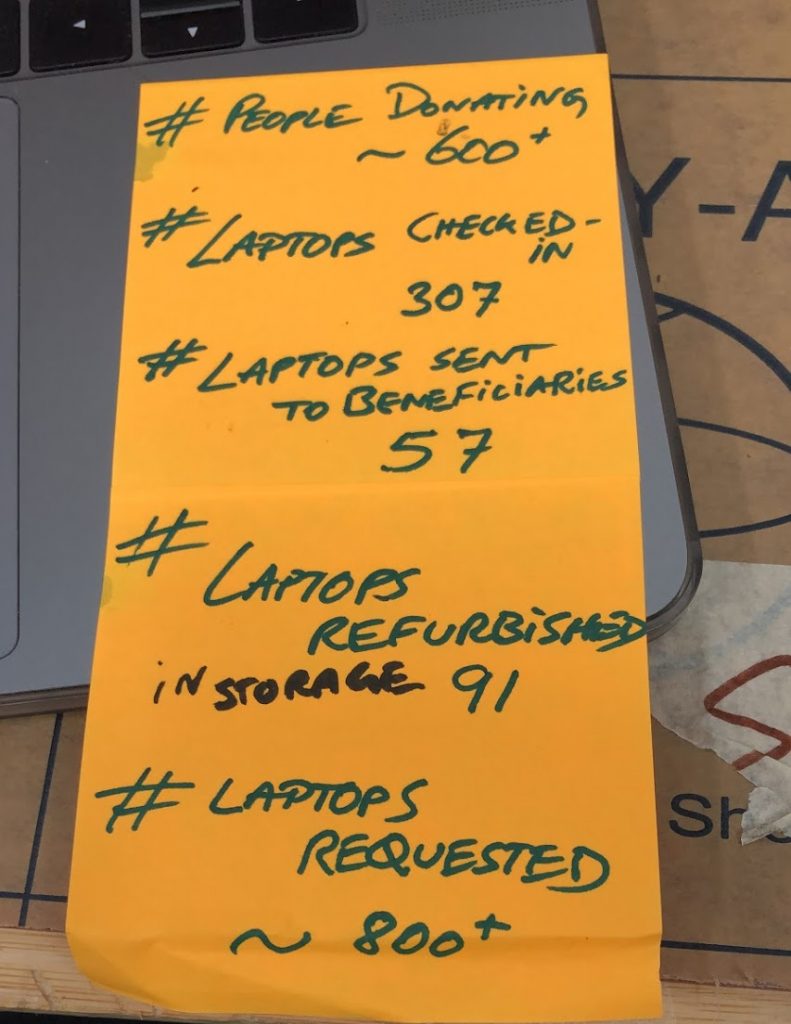

From the eight laptop requests last week, today—just a week and a half later—that number has mushroomed hundred-fold to 879. The group is also talking to the Ministry of Education (MOE): How can they work together to support these families? Why, in the first place, are there families who were not properly equipped before HBL started? Is there a digital divide in Singapore that schools are widening, not bridging?

For instance, they teach caregivers of cerebral palsy patients how to turn a $5 doorbell button into one that works with assistive technology devices. These buttons are important because they allow patients to get used to physical stimuli of various shapes and pressures; the buttons can also be used to operate mechanised drawers, for example, that patients are otherwise unable to open.

But manufacturers of assistive technology devices often charge upwards of $50 for one button.

“And that’s just a button, not including the thing that the button turns on,” Saad exclaims, incredulous.

Engineering Good, in other words, makes assistive technology accessible to people who need them the most.

This is how the process works:

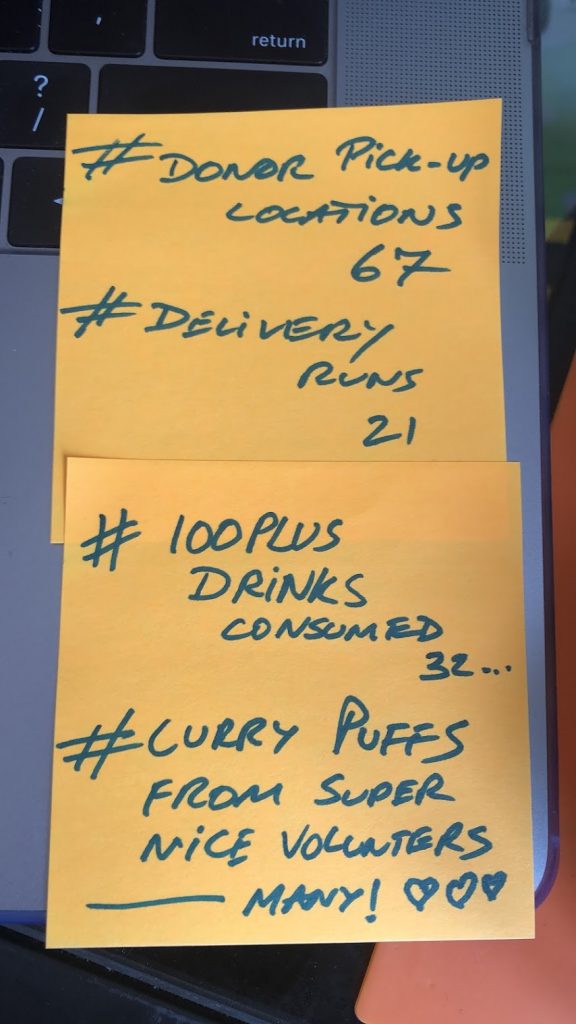

First, people who wish to donate a laptop—regardless of its working condition—and any spare accessories, such as mice or laptop bags, fill in a form online.

Next, a volunteer will pick up the laptop and send it to the nearest of Engineering Good’s 12 distributed processing centres (DPC)—”which is a fancy way of describing [the place where] a bunch of geeks who have no life fix laptops,” Saad laughs.

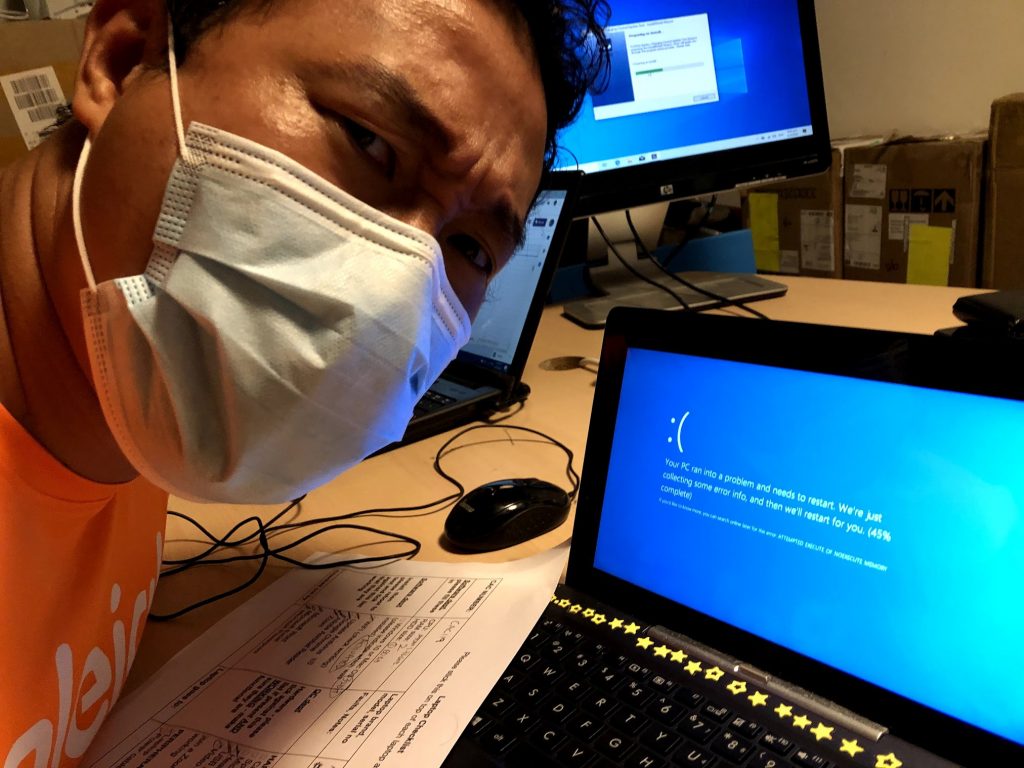

At the DPC, a tech-savvy volunteer will sanitise the laptop and try to boot it. If it doesn’t work, they will check the internal components, reinstall Windows, and so on, until they resurrect it.

Once 5 to 10 laptops have been refurbished, a volunteer will courier them to Engineering Good’s head office at Henderson Road. There, the logistics of sending these laptops out to beneficiaries will be handled by another team of volunteers.

“When you install Windows, it’s an exercise in patience. And if you install Windows on a clunky old laptop …” Saad groans, the silence that follows capturing his frustration.

So volunteers don’t only need the technical expertise, but also supernatural patience. Saad estimates that it can take hours just to refurbish one laptop, though he can work on a few of them simultaneously while he waits for Windows to finish installing.

Furthermore, because of privacy issues, some laptops are donated without a hard disk drive, so volunteers have to scavenge components from unsalvageable “craptops” and put them into these hollowed out laptops, creating a “franken-laptop”.

And this doesn’t even take into account the logistical headache volunteers face of matching and delivering laptops to beneficiaries, a task made more painful by the circuit breaker measures.

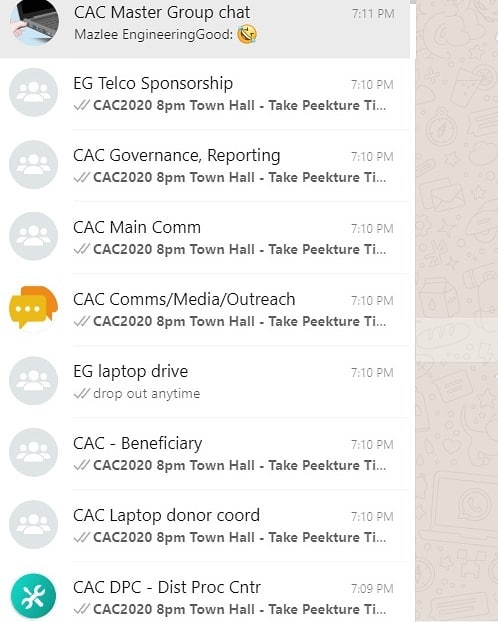

In fact, prior to launching their Computers against Covid campaign, Engineering Good only had 4 to 5 volunteers. Within two weeks, they now count 85 people—as of 17 April— who have signed up to contribute their time and labour despite most having other commitments.

Saad himself is juggling a full-time job with his volunteering efforts. I ask him how he balances the two.

“Badly. Very badly … I think I’m going to get fired soon,” he laughs.

“Half the day I spend with [my company], the other half at Engineering Good … weekends are completely a blackhole. I go to [Engineering Good’s office] on Friday and I’m back [home] on Monday.”

Saad pauses.

“What’s the date today?”

“[Singapore] has WiFi coming out of our ears. If our WiFi goes down, everybody freaks out, everybody looks for me, the Indian tech guy, to fix the WiFi.’”

Saad is speaking satirically, but like all satire, it has its basis in truth. Just two days ago, the whole RICE office panicked when StarHub’s internet started dying in patches. As a nation, we’ve taken fast and seamless internet connection for granted. It’s almost inconceivable that any home in Singapore does not have WiFi.

Statistics concur. Singapore’s Wireless Broadband Penetration Rate in Jan 2020 was 190.5%, which suggests that each person in Singapore has more than one smartphone and more than one internet connection.

So, as Saad points out, it is puzzling—and concerning—that there are families whom we don’t know about who do not have the ability to provide their children with a laptop and internet connection.

“What this seems to reveal,” Saad reflects, “is that [this digital divide] is common. It’s more widespread than we thought. We have very little visibility into these gaps across Singapore.”

“This is not a tech problem. This is a social problem.”

As Saad implies, there are larger structural cracks in Singapore society that have given rise to the wound Engineering Good is attempting to staunch. But these are issues so fundamental that a small non-profit organisation like Engineering Good is by no means able to address.

“So we started talking to the agencies,” Saad says, “the normal channels that are supposed to fill in this gap.”

Saad emphasises that these channels have already initiated some support schemes.

For example, MOE has loaned about 3300 laptops to students after the HBL announcement was made. A CNA article reports that “MOE expects more students and parents to come forward on Monday and Tuesday, before the first day of full-home based learning on Wednesday, and is prepared to loan out more devices.”

In addition, the Infocomm Media Development Authority runs a NEU PC Plus Programme that allows disadvantaged households to buy a new computer at a subsidised rate.

Saad is not privy to the discussions with MOE either: they are being handled by Johann, Engineering Good’s executive director. So he can’t comment on the principles shaping Singapore’s social and educational policies.

All he knows is what the numbers on the ground tell him: “Yes, it is true that [3300] devices are going out … but it leaves people with a false impression that it’s going to be more than enough. There is still a minority group that somehow doesn’t qualify.”

“We are just organically picking up people, like Rebecca, who fall into the gap.”

But there are still 719 children waiting for a laptop so they can carry out their HBL. Even though people have pledged approximately 700 laptops within two weeks, only 40% can be refurbished, Saad says. Engineering Good still needs more laptop donations so no child is left behind.

And despite the disheartening reality of underprivileged families in Singapore falling through the cracks, Saad is remarkably optimistic about the situation.

Yes, there are gaps in the system, Saad acknowledges. But there’s a silver lining to it.

“I am Indian but I have been in Singapore for 20 years … In India this would not even be a thing. It would be a dream for me, as an Indian, to be able to reach out to a ministry and even have them listen.”

“Singapore has got everything it needs. It has the ability to respond to the situation. It has agencies that are listening, it has agencies that are talking … It just needs to work.”

In the meantime, as the agencies are working on patching these holes, the community—among them, Engineering Good and its volunteers—has stepped up.

“There are skilled and experienced people who are channeling their skills to bridge it.”

“I’m generally very cynical. I feel like we’re living in a Black Mirror episode, mostly,” Saad laughs. “But this … It sort of restores my faith in humanity.”

Any thoughts on this story or why families in Singapore are unable to afford laptops? Tell us at community@ricemedia.co.