Top image: NanyangDaxue.Sg/Facebook

My Chinese teacher once warned me not to equate Nanyang Technological University with Nantah. Making that connection would anger many from the Chinese community who lived through the 1960s and 1970s, he said.

But aren’t both the same? Whenever I read the Chinese newspapers, headlines often abbreviate NTU as Nantah.

Apparently not.

After some digging, I discovered that although NTU celebrates its 30th anniversary today, its origins started way before that with Nanyang University, also known as Nantah in Mandarin. Opened in 1956, it was a different entity from the current-day NTU.

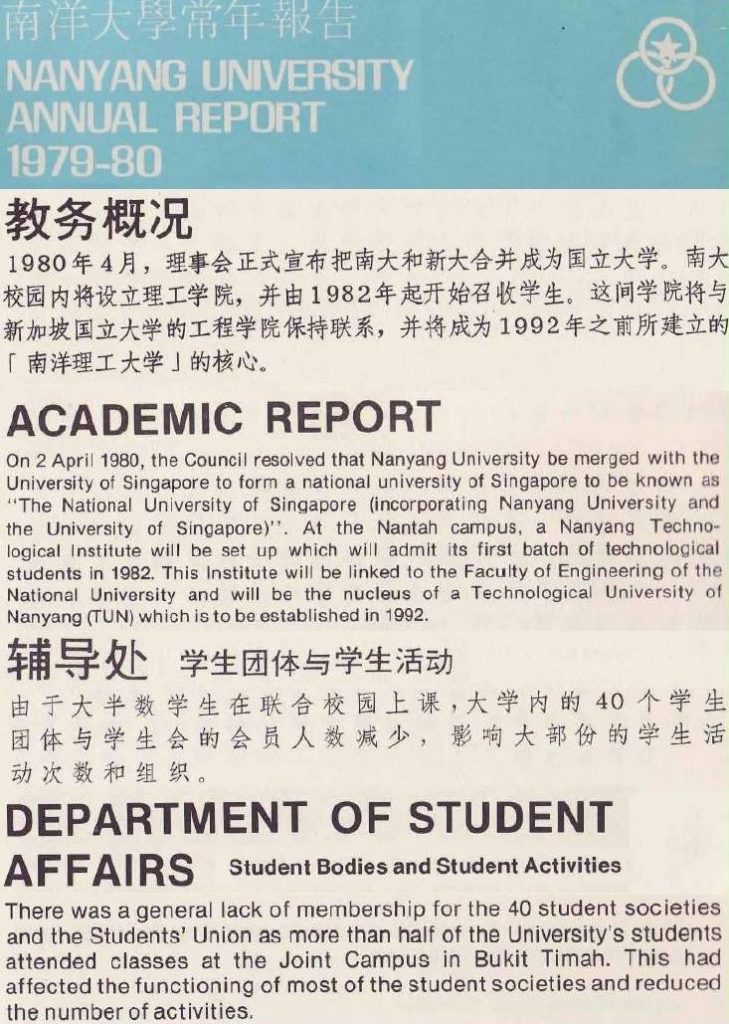

Based on official narratives, such as those by founding prime minister Lee Kuan Yew in his memoirs, and numerous committee reports which reviewed Nantah, the university merged with the University of Singapore in 1980 to form today’s National University of Singapore because fewer students wanted to study there.

After all, Nantah was a Chinese-medium university, and increasingly, fewer students were attending Chinese-language schools. Under these circumstances, then PM Lee announced the merger.

NTU is 30 years old today, but to focus only on the university’s post-1991 history will be an injustice to the Nantah years—and also to its former students, many of whom are still with us. It is crucial to narrate their stories and understand the sacrifices they were forced to make in Singapore’s pursuit of progress, before it is too late.

Nantah: The Stormy Years

I decide to find out more from Mr Yap Kin Loon, whom I meet at his fairly-spartan flat in Ang Mo Kio. He studied in Nantah from 1964 to 1966.

Interviewing the 80-year-old self-employed accountant, it is clear that Nantah had a tumultuous and controversial past which runs contrary to official narratives—a sentiment similarly shared by Professor Tan Kok Chiang in his 2017 book, My Nantah Story.

Speaking in Mandarin, he tells me: “When I entered Nantah in 1964, the situation on campus was already tumultuous, with the protests and all.”

In his time at Nantah, Kin Loon majored in Chinese language and Culture, and prior to that, he studied at The Chinese High School (today’s Hwa Chong Institution).

He furthered his studies to have an easier time finding a job later. Considering it was less common to study in a university then, I reckon Kin Loon performed very well in school (he denies this); his tuition fees were also paid for by a bursary.

From the onset, Nantah already played second fiddle to its counterpart, the University of Singapore, as its degrees were not officially recognised until 1968. At the time, the colonial government was worried the university would breed leftist radicals to advance pro-communist ideas and subversive activities.

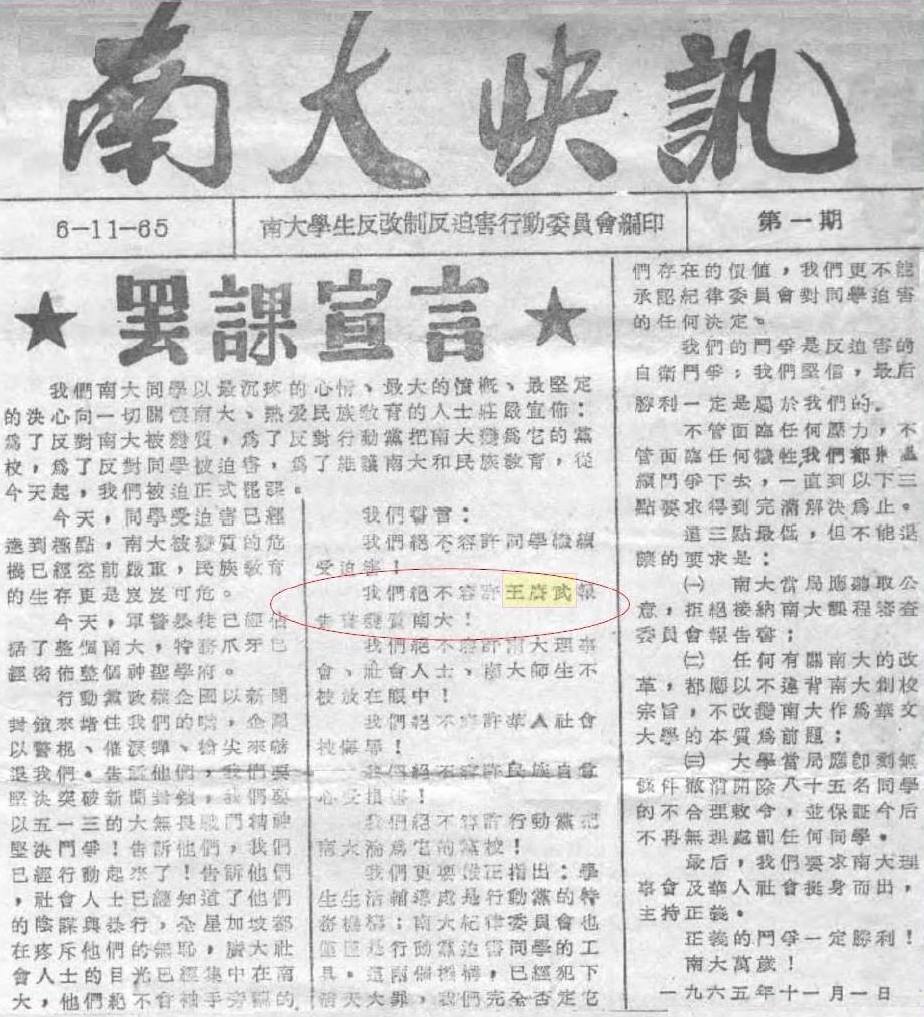

Then there was the Wang Gungwu report, as Kin Loon recalls, which caused a groundswell of dissent among students. Prof Wang, then a history professor and dean of arts at the University of Malaya in Kuala Lumpur, helmed the Curriculum Review Committee formed by Nantah in February 1965.

In his report, Prof Wang recommended language reforms in the university, which included not making Mandarin the only medium of instruction. Kin Loon says the government felt that the Chinese language did not reap any benefits internationally then.

“We were all very against it, as Chinese-educated students. All of us wanted to protect the Chinese language,” he says.

With that reform, Nantah’s raison d’etre as an institution which used Chinese as the principal medium of instruction and its reputation as the highest-level institution in the Chinese education system would have been lost, according to Tan Kok Chiang’s My Nantah Story.

The students went as far as to stage a protest against the recommendations, and as a result, 85 were expelled from Nantah. These demonstrations continued from the early to mid-1960s, and students deemed pro-communist were continually arrested during raids.

Merger Of Two Universities

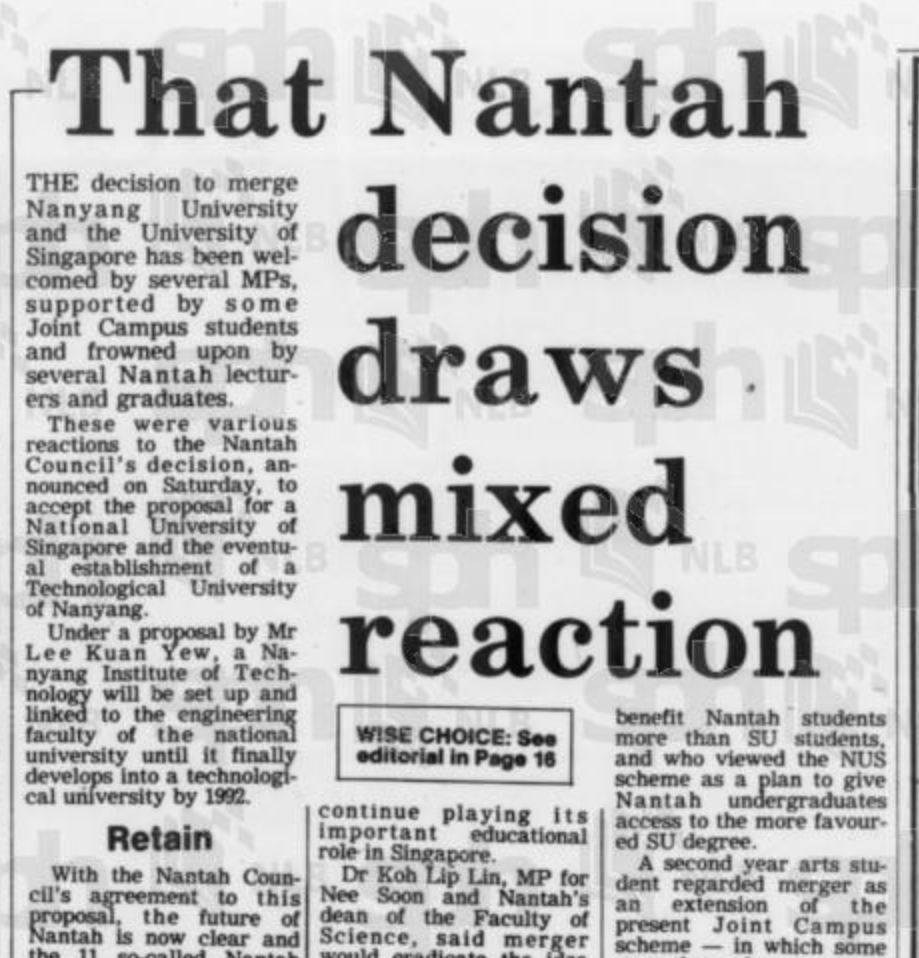

The writing was on the wall, however, and despite an exchange of letters between the government and university management (which included prominent businessmen Wee Cho Yaw and Lien Ying Chow), and a petition by the student union to protect Nantah’s autonomy, the university eventually merged with the University of Singapore in 1980.

Going by the official narrative, Nantah was merged because of its declining enrollment. Intentionally or unintentionally, the merger also quashed any political uprisings from the left-wing faction of the Chinese community. Kin Loon confirms that many in the university were leftists.

The decision was framed as a merger instead of closure. “The Government did not want to be seen as eradicating Mandarin—that’s their motive,” he says.

I feel his sense of helplessness, as he explains that the merger was beyond anyone’s control. They were more heartbroken than angry.

He and his friends from Nantah did all they could to protect the university which they were fiercely proud of, because it was built brick by brick with contributions from all walks of life in the Chinese community, from towkays to rickshaw pullers.

There were Chinese high school graduates who put up a concert that raised $62,596 and 1,200 trishaw drivers who raised $21,535, and they donated the money as part of a crowdfunding effort to build Nantah.

Not only was Nantah the pride of the Chinese community, as a ground-up university funded by people themselves, students also felt that Nantah’s demise meant a blow for Chinese education and culture as their roots would get cut off, according to Tan Kok Chiang. They didn’t want this cultural identity to be lost.

What’s admirable about these Nantah students, however, is their fighting spirit. Although the future of their school looked bleak, they fought for what they believed in by protesting and demonstrating, even if they had to pay a heavy price.

But their efforts were for naught.

“The Government’s power back then was too strong. There is no way for us to really fight back. If we don’t listen, we will get nabbed,” Kin Loon says.

Arrested

With such a history, I wouldn’t be surprised if the government then perceived Nantah students as troublemakers or anti-establishment.

Students like Kin Loon himself.

In fact, he reveals that he himself was arrested back in 1966 during a police raid, with eight others. The Malaysians among them were banished from Singapore and permanently disallowed from re-entering.

When the raid occurred, Kin Loon was staying in the school dormitory. He recalls police officers surrounding the campus in the dead of the night, and making their way up to the rooms. Knocking on their doors, the officers stormed in and arrested the students.

The Internal Security Department told him he would be detained and labelled him as one of the masterminds behind a demonstration over PM Lee’s earlier visit to the university.

On 30 October 1966, Lee had visited Nantah to open a new $1 million library building, and many students were up in arms against his visit because they were upset over unfair treatment by the Government towards them, in particular over language policies.

“But on that same day, I was participating in a sports meet as a long-distance runner. There was no way for me to be involved in the protests,” Kin Loon claims.

The officers did not believe his words. He was thrown behind bars and expelled from Nantah. His bursary was revoked. Kin Loon was only in his third year of his four-year course.

“I really didn’t know what I did wrong. I didn’t interact with the radicals on campus either.”

He seems quick to distance himself from the so-called “radicals”, an unpalatable label often used by the establishment referring to activists who resort to social movements when pushing for reforms, although it remains unclear if they were really radicals or simply passionate students protecting Chinese culture.

At the time of arrest, Kin Loon was merely a member of the university’s Chinese cultural society, where like-minded students got together to analyse literary works.

He wonders if his membership in that society had anything to do with his arrest, although the society he was in was innocuous and its members did nothing sinister.

Another possible reason: an act of sabotage by peers in school who did not see eye-to-eye with him and snitched on him to the authorities. “Maybe they think we attended some illegal activities—that’s my guess,” he says.

Life was not tough inside prison, Kin Loon says. But little did he know how things would change after his release.

Life After Detention

Two months later, when the authorities no longer perceived him as a threat, he was set free.

Expelled from university, there was only one thing he could do: work. He took up logistics and warehouse management jobs in Jurong, which paid him about $100 per month. But he kept encountering roadblocks, thanks to his stint in prison.

Each time, he would start work at a company, only to be dismissed a few months later due to his imprisonment record. Wash, rinse, and repeat for two to three times.

“I asked for the reason behind my dismissal and they kept mum about it. But I understood,” Kin Loon laments with a palpable sense of helplessness.

The next two decades were a tough ride for him. From the 1970s, Kin Loon took up accounting courses and became a certified accountant, working at smaller accounting firms which, strangely enough, did not take issue with him being blacklisted. It was an easier way out to be an accountant, and the money was decent too, he says.

Eventually, he set up his own accounting firm, IPT Services, in 1999. The springy senior citizen is still working there till this day, with his son helping out.

“Time To Let It Go”

Before interviewing Kin Loon, I expected to meet an old man still resentful over what happened to Nantah and the treatment he got from the government.

This is still the case for some of his friends, where the mere mention of “government” is enough to provoke them. These former Nantah students are still angry after all these years because they perceived Nantah’s closure as politically-motivated, and also an abolishment of their language and cultural rights by the government.

As for Kin Loon, I see a zen-like man who seems to have put those episodes aside—even though he was detained, expelled from the university, and had career plans thwarted (he wanted to be a teacher).

Whatever happened decades ago no longer affects him now. His children lead uneventful lives, unaffected by the blacklist which plagued their father. It seems the struggle behind Nantah belongs to a bygone era.

Although Nantah is history to us, it is a lived reality for many others. The university was an entity built by the Chinese community and a source of identity for them. Yet, it was taken away from them 24 years later.

Many had difficulties finding jobs and were looked down upon by certain segments of society because of the prejudice created from persistent fault-finding with Nantah, according to Tan Kok Chiang.

Even without the “leftist influence” conspiracy theory behind the merger, Nantah’s days would still have been numbered as Singapore developed into a predominantly English-speaking society. The demise of the university was inevitable, and a generation of students had to be sacrificed for the greater good of progress.

In recent years, the Government has tried to make up for the blemishes in Nantah’s history, be it efforts to resurrect the “Nanyang University” name or the creation of a Chinese Heritage Centre at the former administrative building of Nantah. But reactions to these attempts have been mixed.

What’s admirable about these Nantah students, however, is their fighting spirit. Although the future of their school looked bleak, they fought for what they believed in by protesting and demonstrating, even if they had to pay a heavy price.

NTU is 30 years old today, but to focus only on the university’s post-1991 history will be an injustice to the Nantah years—and also to its former students, many of whom are still with us.

Before the ISD knocks on my door and nabs me for attempting to incite unrest, let me reassure you that I’m not asking everyone to take it to the streets to protest against the next government policy we are unhappy with. We must understand that those acts of civil disobedience took place in a different era under a very different political context.

This is why Singapore’s move towards English as a lingua franca—a policy we take for granted—was not smooth-sailing and was met with resistance. It happened at a time when the Singaporean identity was still in its infancy, and the Chinese had a stronger tribal attachment to its own ethnic group, culture, and language.

Today, even though he remains heartbroken over the Nantah affair, Kin Loon no longer bears grudges towards the Government.

He sighs and gives a philosophical response, typical of those from the pioneer generation with a can-do spirit: “In life, people have different fates. You just face and deal with whatever that comes in your way. There is no benefit to grumbling over it all day long and I have already let it go.”