After all, there was nothing particularly scandalous about her chronicle. Yes, there are mentions of overcrowded hospitals. Yes, she demands accountability from her local officials, but Fang Fang was hardly an investigative journalist breaking new ground. Much of what she covered could be found by stumbling blindly around Wechat, where there was a brief blossoming of dissent in the immediate days after the lockdown was announced.

No fingers were pointed at Beijing, nor was it suggested that such a crisis had emerged out of China’s political system. President Xi Jinping appears a grand total of once–in the translator’s endnotes.

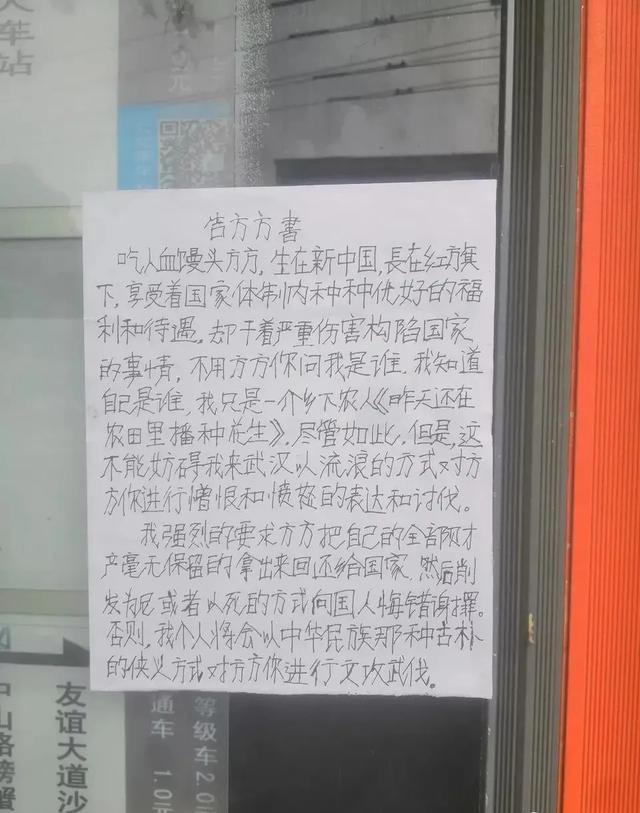

And yet, many did take offence as the blog grew more and more popular (attracting around 100 million readers at its peak). First, the critics claimed that she had fabricated many of her ‘doctor’ friends. Then, the CCP IB attacked in force. They accused her of being a ‘running dog for the Americans’ (一条美狗), of feeding off the misery of Wuhan’s residents, and for ‘selling out’ in general. An anonymous high school student (with 100,000 Weibo followers) wrote a letter attacking her on social media, prompting responses from other high-schoolers, as well as right-leaning academics, government-linked trolls and much more. The end result can only be described as a shitstorm—the largest in China this year.

My first response upon finishing the book is a profound sense of anticlimax. Huh, is this it? After all the controversy and accusations of treason, the actual text is extremely underwhelming. If this is what working for the CIA entails, nobody would sign up.

Every entry begins with a very British discussion of Wuhan’s weather (先下大雨,中午大晴), followed by a short passage on her mood (只想待在家里) . From there, her thoughts move onto more ‘relevant’ subjects, like the hospital’s poor ventilation, or the Hubei natives who were just then being ostracized as lepers in other provinces.

There are many conversations with friends and doctors serving on frontlines, but the diary itself, like most true diaries, is rather short on high drama. This is no Decameron. There are no accounts of dead bodies piling up on the streets or wealthy women turning to prostitution in order to secure medical care.

Instead, it’s almost aggressively banal. A neighbour brings Fang Fang the ingredients for fish soup, dropping it off at her door. She thanks him, then laments that she has so much food in her fridge she could not possibly finish it alone. She shares some of her food with another neighbour and drinks the soup while thinking about some article she read in the Yangtze Daily. Afterwards, she feeds her dog and worries about the dwindling dog food supply.

Suffice to say, Netflix will not be adapting it anytime soon.

Local government officials are relentlessly questioned for their role in downplaying the epidemic during its early stages. Why, she asks, was a 40,000-person community banquet allowed to go on mere days before the lockdown ensued? She rightly calls this lapse a ‘form of criminal action’ on the part of its organizers.

Likewise, the medical team who were sent to investigate the plague gets a beatdown for telling everyone that Covid-19 was ‘Not Contagious Between People, It’s Controllable and Preventable’. (人不传人, 可防可控) When evidence to the contrary grew insurmountable, they did not even bother to ‘express one ounce of regret’ over their mistake or to offer the slightest ‘hint of an apology’. Instead, one doctor, Dr Wang, even had the audacity to turn himself into a martyr by saying: “If I hadn’t gone into some of the patients’ rooms and the sick ward, I wouldn’t have been infected myself!”

In response, Fang Fang rightly cursed him to hell. She also demanded the same accountability for Dr Li Wenliang, the persecuted whistleblower, from the administrators of the Central Hospital in Wuhan where Covid-19 had spread quickly amongst the medical staff, as well as for all the cancer patients who died because overcrowded hospitals made chemotherapy impossible. In short, she counts the cost in a manner which attracted the ire of China’s ultra-nationalist trolls, who saw her critical stance as an attack not against the Wuhan local government, or certain leaders, or even certain policies, but as an attack on China itself. She was not just a critic, but a traitor who fed off the blood on Wuhan’s people and gave ammunition to the west.

I can list the greatest hits, but I think you already know them by heart. First, there is an imaginary ‘west’ that is not just ‘biased’ and ‘racist’, but well-organized in their maliciousness far beyond the dreams of any State Department official. Secondly, there are accusations of being an ‘armchair critic’ and using the tragedy for ‘personal gain’. Thirdly, a lack of gratitude to the government is quickly upgraded into a charge of treason.

Some of the bolder outlets will even outright accuse you of working for a foreign government because why not? If you frame it in such a way that your accusation sounds like a genuine question rather than a statement of fact, no one can really prosecute you anyway.

The overall effect is neither right nor left, but plays on that ever-useful sentiment: pride. A siege mentality. Us versus them. The irony of your opponents using the exact same arguments seem to discomfit no one, probably because nationalism and patriotism are not about rational arguments, but play on hurt egos and an instinctive gut-level hatred of foreigners.

Fang Fang’s Wuhan Diary is thus remarkable, not because it sheds new light about China’s early handling of the crises (it really doesn’t), or because of its grossly-exaggerated literary significance (it has little, if any). It’s important because it illustrates the struggle of speaking out in a time of heightened jingoism, where dissent is equated to treachery and everyone is suspected of disloyalty; when seeking accountability is forbidden—unless it’s directed outwards towards other countries and foreign bodies.

The irony is, her realistic portrayal of Wuhan during the lockdown, lambasted as ‘unpatriotic’, has since been proven right and true and universal. Who doesn’t feel ‘a sense of fear, helplessness and anxiety?’ (恐慌、无助、焦虑、紧张) Who doesn’t want a ‘good cry’ when it’s all over? Much of what she described in Wuhan Diary, far from being bleak, is extremely relatable as the lockdown commenced around the world. Much like Singapore during the early days of covid-19, the journalists of Wuhan had a brief moment of panic when the daily case count was delayed by accident. Pregnant women, whether they are in Wuhan or Woodlands are all under a great deal of stress as they bring new life into a changed world.

Unfortunately, it is not just criticism which has been outlawed. Negativity has also become a taboo subject as the central government tries to promote positive energy (”正能量“). The question is, when does positivity cross the line from cheerleading into censorship?

As for the mistakes, everyone will blame everyone else until it emerges that neither the PAP, nor the CCP, nor the Trump administration, nor Boris Johnson, nor Bolsanaro had made any mistakes in their handling of the outbreak. Singapore is great. China is great. America is great. The world is great. Everything is great. It was a great pandemic where everything was beautiful and nobody died.

It is against such triumphalism and false positivity which Fang Fang makes her stand. “Remember, there is no such thing as Victory here,” she writes, “there is only the end.” (记住,没有胜利,而是结果)Perhaps this is the real point of Wuhan Diary and other ordinary accounts of life during the Pandemic. Without them, we would be swept away by the relentless firehose of bullshit which turns every tragedy into an opportunity for triumph.