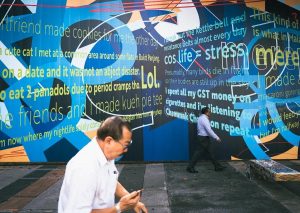

Just over 3 months ago, my sister took me to the A&E after I broke down at work. I hid in the staff toilet the whole time because I couldn’t stop crying. My supervisor had to come and physically remove me from the toilet, and even then I was inconsolable. I hated the fact that crying didn’t make me feel better. In fact, the more I cried the more hopeless I felt.

Suicide became a very tempting option. A quick escape. An immediate solution to everything. With each passing minute, I was putting together a more detailed suicide plan. No one felt safe to let me go home. I didn’t feel like I could keep myself safe. So when the doctor offered me inpatient admission at NUH, I said yes.

I said yes, because when you’re at that stage where you feel so defeated, miserable, and desperate, you can either find the courage to kill yourself, or find the courage to admit yourself. The latter is always an option. I said yes because I saw how harmful and toxic my behaviour was to the people I loved. They needed as much space and time away from me as much as I needed time and space for myself.

I was wheeled into the ward even though I told them I could walk. Security door access – I was told that even staff from other wards couldn’t enter. Windows that resembled prison bars. I heard the magnetic door shut behind me, signifying the last of my autonomy being surrendered. I felt everyone’s eyes on me. Wheeled in, plain clothes? “The new girl”. I saw patients in green and brown seated in the common area, and all stopped their conversations to stare at me. I was scared shitless because of all the things I’d heard and seen in movies about psychiatric wards. I was expecting to see people banging their heads against the wall, wandering around with blank looks in their eyes, screaming while being tied down, or being aggressive towards me.

While I did experience some of that, you only fear because you don’t understand. I learnt that there is a reason for everything you see. If you are being tied down or injected with sedatives, it is likely because you pose a substantial threat to yourself, or to other patients and staff. People can be aggressive because of the symptoms they are experiencing. People can look zoned out because of side-effects from their medication— I experienced that myself.

At the same time, the people I got to know in this ward were also easily some of the most sensitive, mature, and empathetic people you could ever meet.

In any case, these are some of the lessons I’ve learnt after being admitted to a psychiatric ward:

My father figure, whom I will refer to as “Uncle”, was so hurt to find out that I wanted to discharge myself, then kill myself. He said, “But you have so many people who care for you and love you. Like me.” I told Uncle that I knew that. And even if I had plans for the future that I can be excited about. Even if I could tell him about my plans to apply for BTO, to get married, and start a family, I could still decide to kill myself.

2. But when people tell you they want to kill themselves, it’s a cry for help. So help them.

When people feel suicidal, it is likely that they are at their wits’ end. They feel like they have tried everything but nothing has worked. They still feel as terribly as they did before they tried, which makes them even more helpless and hopeless. So firstly, acknowledge that it is okay to feel depressed/angry/anxious, etc. But be frank and let them know that it is not okay to behave in the way they are behaving, whether it’s cutting themselves or wanting to kill themselves. Constantly remind them that while you may never understand how they’re feeling and what they’re experiencing, you’re there for them. Show some empathy.

Which brings me to …

Communication and active listening skills may come naturally to some, but for many, they require conscious effort to learn and practise.

Step 1: Show that you’re listening. Make eye contact. Nod. Reflect and summarise what the person’s saying.

Step 2: Show empathy. Name and acknowledge their feelings. Say, “I can see that you’re feeling ____. It must have been very difficult for you to (insert reason and show that you have been paying attention).

It may seem awkward at first, but it really helps. And when it comes naturally to you it’ll be even more effective. And then you can teach others.

4. Staying in the ward can be a well-needed respite.

I felt like I had been living on edge since the start of this year. So being warded gave me ample time and space to rest and reflect on what has happened. There is a reflection corner in the ward, complete with artificial grass, parquet flooring and the only mirrors you will find. Three large full-length mirrors (made of polished metal of course—they didn’t want people to break it and cut themselves). It was there I spent a lot of time thinking and reading. Being away from social media, work, people, and from my usual routine allowed me to give my mind and body a good rest, all while getting the appropriate support. I was given a safe space to gain insight of the thoughts and behaviours I displayed with the help of a multidisciplinary team.

Prior to my inpatient stay, I was already seeing a psychiatrist as an outpatient, where I was diagnosed with anxiety and depression. While the medications helped to control some of the anxiety symptoms I was experiencing, medication itself was not enough for me to manage my overwhelming emotions and suicidal thoughts. Inpatient admission gave the medical team more time to explore the causes of my symptoms and behaviours. It was only then my diagnosis was revised to ‘adjustment disorder’.

It was very helpful when the psychologist in the ward provided me with new perspectives on the issues I was struggling with, and challenged some of the unhealthy thought patterns I had. The mental health occupational therapist helped me to brainstorm different strategies to calm myself down when I’m feeling distressed, such as using a weighted blanket or essential oils, and encouraged me to return to my leisure activities, like writing and playing the piano. I felt more like myself again when I found myself returning to a healthier routine and enjoying my usual hobbies again.

6. Just remember that sometimes, even healthcare professionals working in a psychiatric ward may not be able to provide the help that you want them to.

Not all the doctors you speak to are specialised in psychiatry/psychology. Only the consultant a.k.a. my psychiatrist is. So, not everyone will have answers when you ask them about your treatment plan, because I was often met with, “That was what the consultant suggested.”

Additionally, not all nurses and allied health professionals working in a psychiatric ward are knowledgeable about trauma-informed care. In my experience I felt that the medical team did not know how to effectively manage me when I was feeling the most suicidal. When I told the doctor that I was feeling suicidal but I wasn’t going to tell him my suicide plan, all he could ask me was if I was going to do it in the hospital.

I guess it’s just like what my psychiatrist shared, “Medications form only 30% of the equation. The majority of the remaining 70% would be just you.”

Therefore, it is important to …

I was warded was because I was feeling suicidal to the point where it was no longer safe for me to be left alone. But the real reason as to why I was feeling so immensely miserable was a result of countless uncontrollable external circumstances and the unrealistic expectations I had had of myself and others.

So, figure out the unexpected or uncontrollable external factors that are causing you distress. It could be Covid-19, a new job, new environment, new culture, new rules, medication side-effects, etc. Figure out the unrealistic expectations you had, eg. “I cannot make mistakes”, or “He must be there for me all the time.” Write them down, and then let them go.

Remind yourself of things you can control: your reactions and expectations. Feeling prepared. Setting healthy boundaries and writing down healthier expectations you can have of yourself and others. Identifying your triggers and brainstorming/exploring strategies (a psychologist or an occupational therapist can help you with that). This would likely inform your recovery plan.

8. There’s a limit to how long you should stay. Remember that you’re ultimately still a patient.

There was never a point in time during my stay when I forgot I was a patient. While I was taught in school to humanise people with mental health issues (that’s why you’d always refer to them as “A person/people with mental health illness” and to never categorise them as “The mentally ill”), I saw the value in being treated as a patient. Having to be in patient pyjamas, having to follow the strict ward rules—no phones, no leaving the ward, leaving your toiletries with the nurses to safe-keep … etc.

When I was on suicide watch, I couldn’t even lock the toilet door when I wanted to pee. The nurse had to be stationed outside, with the door slightly ajar. But by voluntarily having my autonomy taken away from me, it kept me awfully and consciously aware of my purpose here: to seek professional help and get better.

As long as it is voluntary admission, you have the right to decide whether or not you want to take certain medications, and you have the right to know what the medication is, and what the possible side effects are.

You also have the right to decide when you want to be discharged. I decided that two weeks was enough because while it was a good respite at the start—I definitely had way better sleep there; away from all the external stressors that were triggering my anxiety—being warded started to give me anxiety. I developed some sort of cabin fever; the rules started to feel stifling, and the fact that I couldn’t even go out for a meal or for a walk felt extremely suffocating.

Plus, I decided that I couldn’t take the overwhelming negativity that came with conversing with some patients. It dawned on me as to why the medical team discouraged us from building friendships here. “They could give you bad ideas,” they said. True enough, a new group of patients asked me, “Did you pick your scenery when you wanted to jump down?”

10. Recovery is rarely a one-way street. It’s a journey which takes a LOT of discipline. So be kind, patient, and understanding towards yourself.

Trust me, you will often feel as though you’re getting better, only to break down and feel like you’re back at square one. But it’s still progress. “It’s like taking two steps forward, one step back,” my counsellor said.

That image made a lot of sense to me. I was so disappointed whenever I experienced breakdowns; when I realised I was still feeling extremely frustrated, crying, and hitting myself over and over again. But I also noticed that I was feeling less anxious, feeling less breathless, and having fewer panic attacks. So pat yourself on the back when that happens and celebrate the small wins! Don’t be so hard on yourself. Think about how you would respond to a close friend if they came to you for help, and if they were having difficulties. Say and write down things like, “You’re making progress”, “You’re trying your best”, “You deserve to be treated with kindness”. Find a way to be healthy and happy first, then you’ll have the capacity to do that for others.

When I spoke to my friend after being discharged, she asked me, “So, how was it like being warded?” I laughed. I told her, “I felt like I was being pushed to my limits over and over again. But because I couldn’t kill myself, I could only learn how to be resilient.” And I did! Sometimes we just need to find a safe space, and if you need it, inpatient admission is always an option you can consider.

12. You will realise who will stick by you through your toughest times.

Duh. You’re very likely facing one of the biggest/worst obstacles in life so far. So if the person is able to handle you at your worst, cherish and appreciate them. Be grateful for them.

On the first day of my admission, I was terrified. I kept crying and shivering and holding onto my sister really tightly—my little sister by the way. In the midst wiping all my tears and snot I said to her, “Thank you so much, I really appreciate you being here for me.” And she said, “Jie jie, don’t thank me. I know you’d do the same for me if I was in your situation too”. (SHOUT OUT TO MY SISTER I LOVE YA)

Also a huge shout out to my partner, who chose to stay with me even though he could have left for the sake of his own health and wellbeing. He never gave up throughout my journey of seeking help. Both him and my sister were the ones who did the research on which hospital I should go to; which doctor I should see. Also shout out to my family and friends, who made the effort to visit and accompany me while I was warded, with the help of my sister who was my personal assistant and organised everything. And of course, my workplace supervisor, welfare officer, mentor and colleagues who have been so kind and understanding.

To the people who are reading this—who may be facing some hardships in life—regardless big or small; who may be afraid of speaking up; who may be afraid of seeking help; who may be contemplating about seeking help; who may already be seeking help, it doesn’t matter.

But do tell yourself this: it must have been really, really difficult for you. But whether or not you have already spoken to someone about it, by acknowledging that it is a problem, you’re already on track to becoming better. It’s going to be a difficult, long, and arduous journey, but have faith. You’re a lot stronger than you think.

One thing you can be certain about is that there are many people who are struggling too. All you need is the social support and the courage to find out about many others who may have similar experiences. Don’t be afraid to reach out to people for help.

Here are some of the 24/7 hotlines you can call if you ever find yourself overwhelmed/distressed and unable to cope with suicidal thoughts.

Samaritans of Singapore: 1800 221 4444

IMH mental health helpline (crisis): 6389 2222

To the people who know/ love/care about someone who is suffering from hardships: Thank you. Thank you for being there. Your person is lucky to have you. It’s not going to be easy for you too. But please don’t give up on the person. Remind them that as someone who cares for them, you’re genuinely concerned for their wellbeing, and you really want the best for them.

If they can’t figure a way out, and you can’t, then maybe it is best for them to try something different. Talk to someone different, talk to someone who is trained. Tell them you’ll arrange it for them; accompany them. Be patient and give them time to consider. Try again and again. Some people find it easier to speak to a counsellor first, so you could approach/contact a Family Service Centre nearby and receive counselling services as appropriate. I personally found it helpful to start from there.

I’m still embarking on my recovery journey. But remember, in a way, we are all in this together.