Yet, with the emphasis on SARS, it’s easy to forget that Singapore has been seized by six pandemics (four flu, two flu-like) within a century. That’s an average of one every 16 years; someone born in the 1950s would be living through their fifth pandemic right now.

What interests me, then, is how Singapore society has reacted to these pandemics. Have we learnt anything from past outbreaks? Are we more prepared to tackle the viral outbreaks, more educated on the mechanisms of transmission? Do we know how to take care of each other better?

Or are the French right in saying that the more things change, the more they stay the same?

What? The 1918 Spanish flu is one of the deadliest pandemics in history. Caused by the H1N1 influenza virus, the flu killed more than 40 million people around the world. It reached Singapore on 18 June 1918; by 8 November, it had subsided.

Numbers? Hard to say—medical and bureaucratic structures were undeveloped then, so it’s impossible to get accurate numbers.

In a paper on Singapore’s influenza pandemics, associate professor of public health Vernon J. Lee, et al., put the number of deaths in Singapore at 2870.

How did we react? Although Singapore’s population was ravaged by the Spanish flu, it seemed that we were spared the worst. The Malaya Tribune, a daily newspaper published in Singapore at that time, reported: “We are not suffering as badly as other countries … Many who have acquired the disease are now back to work and one does not hear whole firms having to close down owing to the lack of staff or whole families being swept away as has occurred elsewhere.”

Clearly, our obsession with the health of the economy (sometimes at the expense of our own) is not a recent phenomenon.

Nor is the practice of racists using the pandemic as a pseudoscientific reason to discriminate against other racial or ethnic groups.

The fatality rate of the 1918 Spanish flu was “disproportionately lower in several more privileged groups like the European communities,” writes Kai Khiun Liew, an assistant professor of communications and information at the Nanyang Technology University.

This led many a racist—like F.W. Field, then Medical Officer of the Malay state of Perak—to speculate on theories of “inherently unhygienic habits” of certain races or going so far as to see the flu as a process of “natural selection” in action.

These are garbage we still hear spewing from the mouths of people—Singaporeans and non-Singaporeans alike—today.

What? The Asian Flu caused an estimated one million deaths around the world. It was first detected in Singapore not on the mainland, but on Pulau Brani on 5 May 1957. But in just three weeks, the Ministry of Health declared the “flu bug beaten”.

Numbers? Again, it’s hard to come up with concrete numbers for the total number of people in Singapore who came down with the Asian flu.

But a case study—or what we think of as a “cluster” today—provides some hints. At the Singapore Naval Base located in Sembawang, a total of 2493 people were infected by the Asian flu, out of a total of 9020 workers. This translates into a 27.6% infection rate, which we can use as a rough benchmark for the whole of Singapore society, as no quarantine measures were put into place.

The total number of deaths was 680, estimates Vernon J. Lee, et al., in the aforementioned paper.

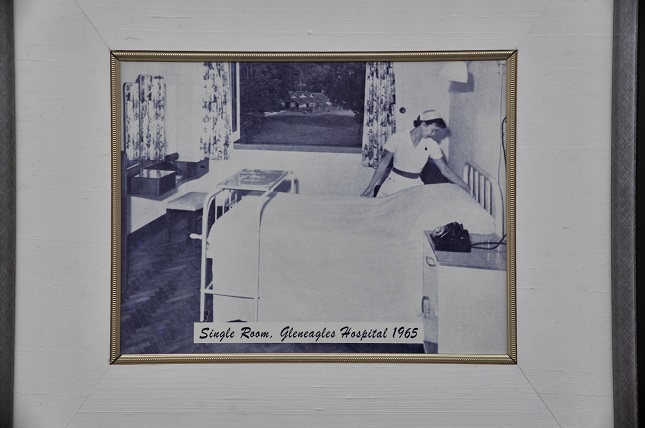

How did we react? First, the positives. Singapore’s scientists, it seems, have always been at the top of the biomedical game.

In 2020, Singapore scientists developed the world’s first test for Covid-19 antibodies.

In 1957, the Asian flu virus was first isolated by a Singaporean doctor, Professor K. A. Lim. This discovery gave us the dubious honour of having the Asian flu termed after Singapore: its official name is Influenza A/Singapore/1/57 (H2N2).

Unfortunately, Singaporeans have always been kiasu and kiasi as well.

In response to the outbreak, Singapore’s then-Permanent Secretary to the Ministry of Health, Dr M. Doraisngham, advised Singaporeans not to wear face masks as they would not prevent the virus: “I don’t want to give false hopes to anyone by asking them to wear it.”

But no one paid him any heed: “dispensaries were packed from early morning until late afternoon”, The Straits Times reported on 7 May 1957.

And, in the 1957-version of supermarket hoarding, “hundreds of Chinatown housewives [bought] carrots and green Chinese olives” after hearing a rumour that the juice of these vegetables could cure influenza.

The one thing that was different is the role The Straits Times played in the pandemic.

Evidently forgetting about the Spanish flu that killed an estimated 2870 people in Singapore just 40 years ago, the paper ran an article with the headline: “SINGAPORE FLU SCARE” and described the Asian flu as “the worst [epidemic] in the Colony’s history”.

It’s a little strange to think that, before the era of POFMA and The Newspaper and Printing Presses Act of 1974—which greatly curtailed press freedom by limiting “management shares” of newspaper companies to government-approved individuals—The Straits Times was as naughty as some of our online publications today.

What? As its name suggests, this pandemic was first detected in Hong Kong on 13 July 1968, and eventually went on to kill an estimated one million people worldwide. It was first mentioned in local media in a 14 August 1968 The Straits Time article, which described it as “a mild outbreak of influenza”. Like the Asian flu, the Hong Kong flu ran its course within a month, and by early September, had virtually disappeared.

Numbers? No hard numbers exist … yes, it seems keeping an accurate number on diagnosed cases was not our government’s strong suit back then.

So, like the 1957 Asian flu, we have to extrapolate from specific case studies. At the University of Singapore, 19.2% of the entire population—i.e. ranging from students to non-academic staff—was infected by the Hong Kong flu.

A Ministry of Home Affairs report entitled “Preparing for a Human Influenza Pandemic in Singapore” estimates that “540 people out of a population of 2 million were killed” by the Hong Kong flu.

How did we react? The Hong Kong flu didn’t cause that much a stir in Singapore because it was, till then, the mildest flu pandemic to dock in Singapore. As the numbers above demonstrate, it was the shortest flu pandemic, least transmitted, and least fatal.

In fact, the Hong Kong flu caused so little stir in Singapore that its arrival was announced only on page 6 of The Straits Times, compared to the hysterical front-page pronouncement of the same paper a decade earlier. Neither did the government impose any quarantine measures of school closures.

One thing that the flu exposed was the schisms money wedged between people. According to Vernon J. Lee, et al., “attack rates were lower for [people] with higher socioeconomic status (6.0% – 20.4%) than for persons with lower socioeconomic status (29.0% – 29.8%), which suggested that socioeconomic status had a possible role in disease transmission.”

Perhaps richer people could afford to stay away from work, to see doctors, or knew more about transmission methods because of their education status. The reason for the disparity in numbers isn’t definitive. But what is definite is that this socioeconomic divide in responses to a flu pandemic still exists today.

What? SARS is technically not a flu pandemic as it is caused by a coronavirus (like Covid-19), not the influenza virus. Still, patients exhibit flu-like symptoms, so, for purposes of this article, it will be considered in tandem with the other flu pandemics.

The first SARS case was confirmed in Guangdong, China, in November 2002. By the time it fizzled out in July 2003, it had killed 774 people out of 8098 confirmed cases.

SARS arrived in Singapore almost exactly 17 years ago, on 1 March 2003. The first SARS patient was a woman who contracted the virus while in Hong Kong.

The pandemic hung around Singapore for approximately three months: the World Health Organisation declared Singapore SARS-free on 30 May 2003.

Numbers? Finally, some hard numbers. A report from the Ministry of Health puts Singapore’s total number of “probable SARS cases” at 238; the first case was reported on 25 February 2003, while the last case 5 May 2003.

A total of 33 people in Singapore died from SARS.

How did we react? With the usual fear, paranoia, panic: we stopped watching movies; we stocked up on healthcare supplies; we avoided beverages with names suspiciously similar to the virus. (The Corona Beer of SARS is … Sarsi. Not kidding.)

But SARS taught us that Singaporeans aren’t all that bad. Set up in 2003 to “provide relief to SARS victims and healthcare workers and their dependents” (among other objectives), The Courage Fund received over $15 million in donations from corporations and the public.

Chua Mui Hoong writes in A Defining Moment: How Singapore Beat SARS that, apart from money, anonymous people also donated fruits and flowers to healthcare workers at Tan Tock Seng Hospital, which was then the epicentre of SARS.

17 years later, the generosity of Singaporeans is playing out the same way. According to Today, about $3.2 million has been raised for The Courage Fund, which will, this time, assist frontline healthcare workers, volunteers, and victims of Covid-19. And, as we keep hearing in the news, people are also handing out free masks and hand sanitisers to strangers who need them.

What? More commonly—though inaccurately—known as swine flu, this pandemic is a resurgence of the deadly 1919 Spanish flu virus, though very much milder. In Asia, it infected close to 400,000 people, causing 2000 deaths. Our first case of H1N1-2009, a Singaporean who had returned from New York, was confirmed on 26 May 2009. But it never really went away—more on that later.

Numbers? Around 415,000 people in Singapore were infected by H1N1-2009 within the span of nine months.

Out of this 415,000 people, there were 21 deaths.

How did we react? As the numbers suggest, even though H1N1-2009 was incredibly virulent, it was also remarkably mild. In fact, this particular strain of the flu virus is still in circulation now, and has now become one of our usual seasonal flu variants.

Therefore, no real measures were taken, nor did we react in any extraordinary way, despite DORSCON being raised to Orange for a good two weeks. I suppose that’s extraordinary in itself.

Yet historical precedence tells us that Singaporeans have been exhibiting the same patterns of behaviour across all six flu-like pandemics that have struck our nation in the past century. No amount of conditioning, so to speak, can change the way we react to a sudden outbreak of disease on our shores.

In other words, maybe we haven’t really learnt anything. We will continue to be fearful, prejudiced, and stock up on healthcare products unnecessarily. But also generous, grateful, and selfless to strangers we hardly know.

These five pandemics—and its latest appearance, Covid-19—tell us that, for better or for worse, we haven’t changed in 100 years.

An earlier version of this article erroneously labelled SARS and Covid-19 as flu pandemics. This is inaccurate: even though they cause flu-like symptoms, they are not considered influenza as they are not caused by the influenza virus, but by a coronavirus. We apologise for the mistake and thank a reader for pointing it out.