What kind of future do you want for Singapore? What values do you think will help us get there?

But six years will arrive sooner than we think. In a series of previous articles, we’ve asked our youth what they want to see in Singapore in the year 2025. They’ve identified values like sustainability, inclusiveness, and having the confidence to navigate a turbulent future.

But our dreams will remain memes unless we take concrete action.

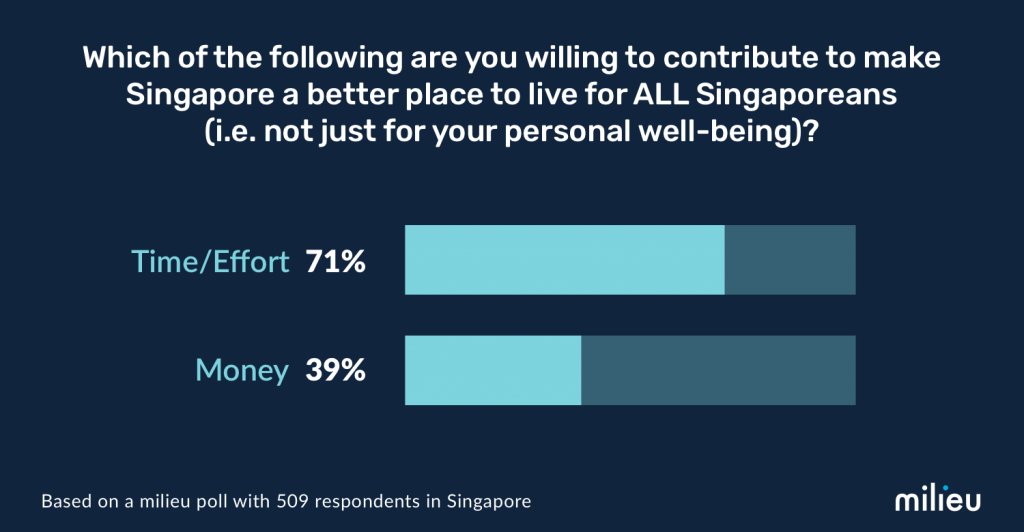

Based on a recent Milieu survey of over 500 youths, 71% of Singapore youth are willing to put in time and effort to make Singapore a better place to live in, while 39% were willing to donate to such causes as well. The question remains: what avenues are there for them to direct their efforts?

How can our youth work towards the future they want? And what are we prepared to sacrifice in order to get there?

I sit down with four of my peers to discuss these questions.

My first two conversationalists talk about how we make Singapore more sustainable. They agree that you can’t consume your way to environmental conservation and solving the climate crisis. Changing your usage to a metal straw is nice, but we have to be willing to put in the effort to reduce and reuse as well.

“It’s why I’m vegetarian,” Adam tells me. The 24 year-old isn’t quite on the vegan bandwagon yet, but he’s getting there.

Adam stresses that it’s nobody’s place to police others about their dietary options. The reality is that many cannot afford to make such decisions. As a very happy omnivore, I heave a sigh of relief.

“This doesn’t change the fact that our current consumption of meat is unsustainable in the long term,” Adam chides. “The point is that from the moment you’re aware of this, what are you going to do about it? You don’t have to go full veggie-lover, but even consciously not consuming meat once, two times a week, can make a small difference.”

He gives me a long, hard stare. “What can you afford to give up? That’s the question you should be asking, and that’s how you answer in kind.”

21 year-old environmental activist Jaclyn believes that our youth have to be green minded and turn our efforts towards the structural aspects of saving the earth. Many climate movements around the world are spearheaded by youth, because we feel the urgency of the matter compared to the global gerontocracy.

Greta Thunberg is one such example. This 16 year-old Swede started the Fridays for Future, a movement that’s catalysed millions. Can our youths press on to lead climate change movements in their own ways?

“Individually, there’s very little we can do,” Jaclyn declares. “But together, we can push for much more. We have to organise with local activists and collectives, and work together with our government. Climate change cannot wait, and Singaporeans need to know that it’s the most important problem we have to combat.”

This means volunteering—taking time and effort to get people together, to change attitudes and minds. Reaching out is tough, it’s tiring, but it’s necessary.

I ask Jaclyn which movements or organisations would be good for youth to get started with, since our Milieu poll from earlier also found that 35% of youth are unfamiliar with ways to contribute their efforts.

“Find out yourself!” she laughs, shaking her head. “Google is free. You’ve got to put in the work yourself because no one is entitled to spoon-feed your education.”

She exhales, but then her voice demurs. “More importantly, do the research to find out which organisations most closely align with your values. Don’t follow what other people say blindly.”

“It’s very easy to be a keyboard warrior and feel that you’re being woke,” Jun Hong laughs. “Liking and sharing is just making yourself feel good. Praxis is about putting in the difficult, dirty work of actually making change.”

The breadth of social justice and inclusivity can be paralysing. There’s race, class, gender, sexuality, physical and mental disabilities/illness—where do we even start?

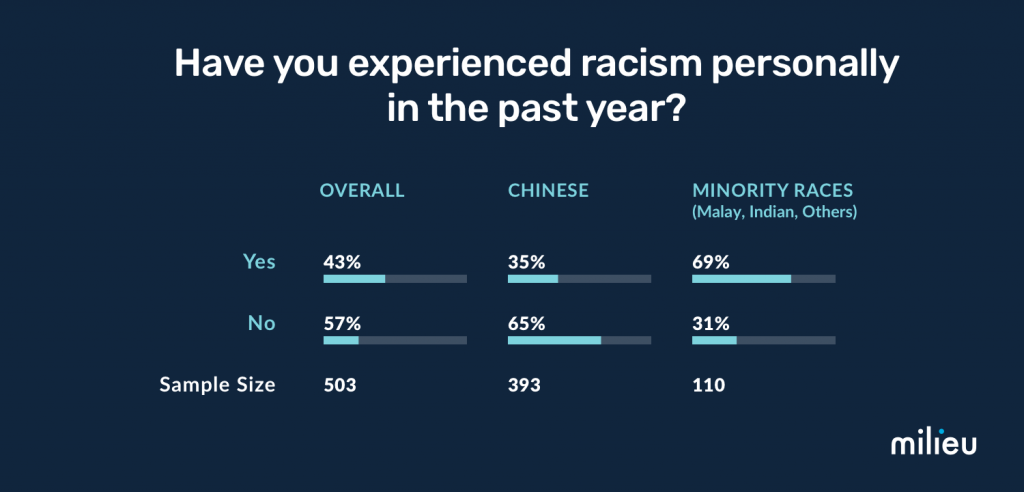

In the advent of the Preetipls/ePay saga, Singapore knows that there’s much to be done with regards to race. 43% of respondents surveyed stated that they’ve experienced racism in the past year, which is frankly a staggering amount. That’s almost every other person.

Breaking down these respondents by race, the numbers are more troubling. 35% of Chinese respondents report experiencing racism, compared to 69% of respondents from minority races.

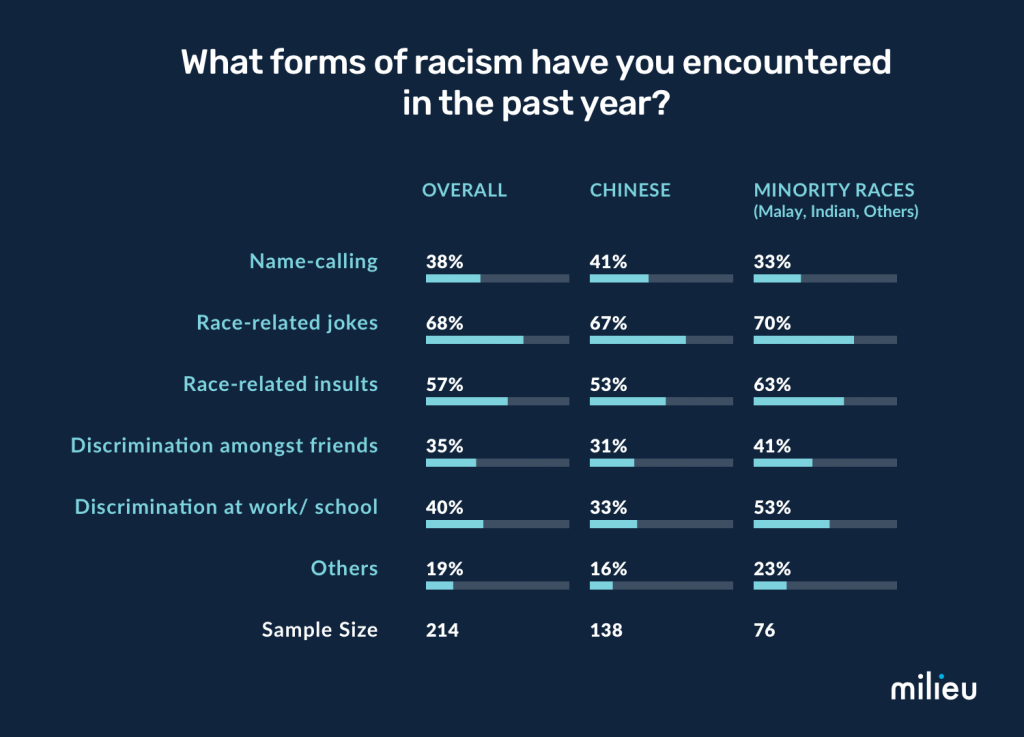

As for the various manifestations of every day racism, the top examples given were race related jokes (68%), insults (57%), and discrimination at work/school (40%). While the first two instances are uniform across multiple races, minority races tend to face more discrimination (53%) as compared to Chinese Singaporeans (33%).

The numbers show that while anyone can be on the receiving end of bigotry, it is our minority population that bears a heavier brunt. How can we make Singapore more inclusive for all?

“Anyone with any dimension of privilege can do two things right away: to listen, and to talk. The trick is knowing when to do what.”

The 22 year-old tells me that this framework acts as a heuristic for him to engage with others daily. “A good rule of thumb is to shut up and listen to marginalised people and talk to people who aren’t, especially those who are close to you.”

“People from a different social group are going to have a very different lived experience from you. When minorities talk about issues that affect them, listen. Don’t challenge, don’t interrogate, just understand and empathise. I know our first instincts are to be defensive, but sit down, be humble.”

“As for talking, face to face is best,” Jun Hong continues. “You’re not going to open the hearts and minds of randos on the Internet.”

Then, who do we talk to? How do we approach?

“People won’t listen to minorities they disagree with,” he says. “We need to have difficult conversations with your loved ones, who can be problematic. There’s no running away from it.”

I mumble something about being uncomfortable talking about the “real stuff” with my family.

“You have to do it because it’s the people who trust and respect you the most who are going to listen to you,” Jun Hong tells me. He lowers his head, deep in thought, as though recounting his own difficult experiences.

“These conversations are hard. But if you care for someone, and they say something racist, or act terribly towards LGBTQ people, you need to step in and tell them that it’s not okay,” Jun Hong says. And then you explain as much as you can why it isn’t. You can address the specific grievances and nuances of the contexts your loved ones live in—something you are intimately familiar with—using language you know will get through to them.”

But there’s more to working towards an inclusive society. We need to respect differences and appreciate one another.

“Use your privilege to uplift others,” Jun Hong says. “You’re a writer, right? Platform marginalised voices, and not just when there are issues concerning them. Let them tell their stories. Who are the sources you’re talking to? Do you have a diverse range of opinions?”

He chuckles as he gestures at himself. “I’m a straight Chinese guy, and you’re talking to me about inclusivity. I’m sure you can do better.”

Before I can let my lobster red face distract me, Jun Hong continues. “This applies beyond writing. When it comes to projects, to your workforce, are you representing marginalised identities adequately? If say, there are very few women applying for this job, why is that the case? How can you rectify that?”

“It’s not about quotas,” Jun Hong clarifies. “It’s about being conscious with your choices and actively including others who are different from you, even if it means more work. Even if it means sacrificing time and effort to reach out.”

He sips thoughtfully on his bubble tea to punctuate his conclusion. “That’s how you become a better ally. The tides come in, and we rise together.”

19 year-old Nadia is starting university in a week. She’s locked into a faculty, but she doesn’t have a concrete idea of her major or career. With the uncertainty about her future, she talks to me about getting the confidence to survive a volatile job market.

She’s not the only one. When Milieu polled for the top 3 aspects of unhappiness in our youth, the cost of living (71%), jobs/economic opportunities (45%), and a lack of mental health awareness/care (31%) were the predominant sentiments. These are all tied into anxieties regarding the workforce and being able to cope with adulting.

“Which is why we should continue lifelong learning using sites like Coursera, Khan Academy, and Skillshare!” she announces, giggling at her peppy imitation of an advertisement.

Don’t mistake her enthusiasm for sarcasm. She strongly believes in taking initiative to pick up new skills and gain knowledge outside of the classroom. The democratisation of information makes it easier than ever to curate your own education.

And because she’s saving up the scant income from her part time job, she cycles through promotional codes from her favourite YouTubers for these sites. It’s tedious, but if there’s a will, there’s a way.

“That’s for technical skills,” Nadia says. “But it’s a meritocracy of connections these days. It’s less of what you know than who you know. That’s why soft skills are just as, if not more important.”

Being someone with middling social anxiety, I return a forced smile that borderlines on the Cheshire.

“Maybe it’s tougher for our generation to reach out these days because we’re so online,” she shrugs. “ I know friends who struggle to be social in a meaningful way, to interact with others face to face. But we have to sacrifice that comfort to reach out to people. Go to events, maybe even strike up conversations in communal areas. Don’t be afraid to ask questions.”

“Plus, most people are really nice,” she smiles. “That’s helped me be brave.”

Meeting the next few decades with confidence will be easier if we’re equipped with the right skills. But talking to Nadia, what’s just as important is having the confidence to imagine the future we want to live in. We need to have the resilience to overcome odds and work towards our ideal tomorrow.

“Older people tell me once you hit your late twenties and early thirties, you become more jaded and conservative. But I find my peers preemptively doing it these days. It’s good to be realistic, but we should harness our idealism to think of the world as not what it is, but how it should be.”

Nadia confides that she’s worried at how competitive university might be, with everyone praying to the bell-curve god and fighting to be above average.

Her shoulders slump. “I think there should be more cooperation as compared to competition. If you help someone out, that’s great, isn’t it?” she says, looking towards me for approval. “I remember during A Levels I’d be so glad whenever someone would reach out to help me with a problem I was struggling with. And when I taught other classmates in kind, it helped me revise and clarify my ideas too.”

She asks me if there are any concrete strategies for fostering a sense of cooperation in university.

“My friends and I have been using Google Docs to take down notes during lectures,” I tell her. “It depends on the context. Sometimes we will take turns to attend if the lecture is really dry. If we’re all there, we will consolidate our own questions and observations, and hash them out later during revision.”

Nadia nods eagerly, haphazardly keying in some notes into her phone.

“If your actions reflect your being in a dog-eat-dog world, that’s the kind of reality you’re perpetuating,” she concludes. “But if you want to live in a kinder world, we have to look out for each other. We have to care.”

“I’ve read Rice’s piece on the romanticised fantasy of gotong royong, so I won’t harken back to the ‘good old days’,” Nadia tells me with a sheepish smile.

“We have to create something new of our own.”

Representational democracy has gifted us with many boons, but it’s also allowed people to disconnect from the political process. There’s a prevailing attitude that we come together every few years to elect our leaders, and then we trust them to govern while we go about our daily lives. Our elected officials and civil servants are the ones to come up with solutions, not us.

But a handful of people shouldn’t be solely responsible for how our country is run. We are all stakeholders, and we must act as such.

Our youth know that the road to change is paved with sacrifice. It’s built on consistent, tedious work that goes beyond a single conversation or article. Each of the youth I’ve talked to know that you have to put yourself out there, to work for and with your community.

Like it or not, we have to sweat, bleed, and cry to create the 2025 we want, just like our forefathers did. But we should never give up to achieve it. Nation building never stops, and Singapore can continue to be a home we are proud to live in.

This article is the last in the Visioning series by NYC, to hear what youths want for Singapore in 2025.