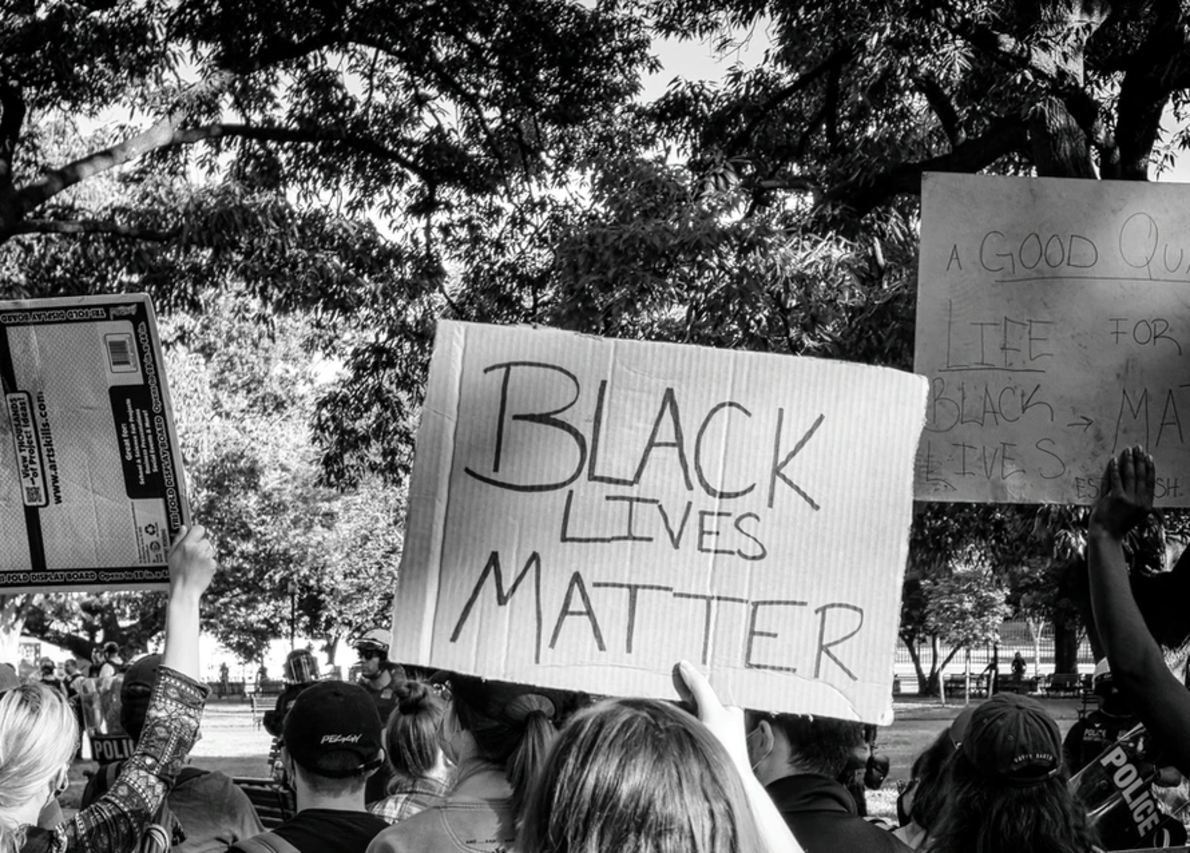

Top image: Obi Onyeador/Unsplash

Over the last few days, my social media feed has filled up with #BlackOutTuesday squares and Black Lives Matter posts—and, slowly but noticeably, began going back to business as usual. Yours probably has, too.

Over the weekend, Singaporeans from bankers to hip-hop artists, advocates to our least ‘woke’ friends, began publicly declaring that they stood with black Americans, promising to learn about slavery and oppression, and pledging to do better in fighting racism.

Just as quick to follow were the reactions to the reactions. As quickly as the squares multiplied, the debate became a yelling match with many complicated strands.

Silence is complicity! Social media is virtue-signalling! Why are you supporting violence? Why are you policing the way people protest?

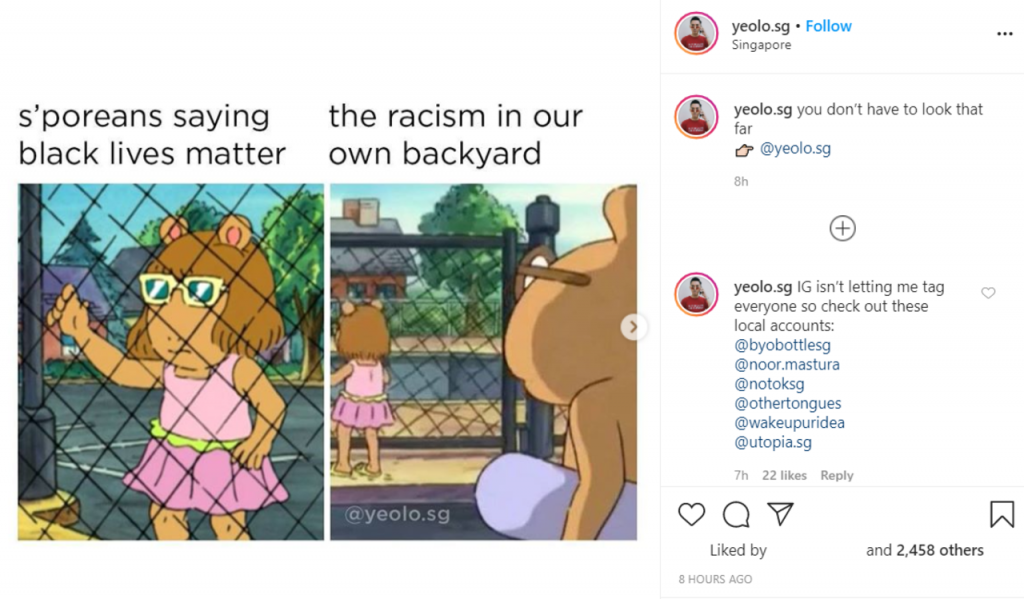

Why aren’t you outraged? Why aren’t you more outraged? Why are you so outraged on behalf of a people you don’t belong to and a culture that isn’t yours? Why are you more outraged about racism in the US than racism in Singapore? Why are you hijacking this movement to talk about other forms of oppression?

What does it mean if you post a black square but use the N-word? What does it mean if you stand with black Americans but were silent about Chinese privilege or migrant workers?

Who are you trying to convince? What does any of this achieve?

None of these questions have been resolved. No social justice movement—let alone one with overseas origins—has drawn so much attention, or polarised debate so intensely, in so short a time.

But while the specific dynamics of Black Lives Matter and some questions it’s raised might be unique, a lot of this also feels like deja vu.

Most of us have watched the campaign progress with a mixture of hope, bafflement, anger, discomfort, guilt, and exhaustion. All these conflicting emotions stem from the recognition that we—especially Chinese Singaporeans like myself—still have so much work to do at home, and that we’ve been in this uncomfortable place before (cc: last year’s outcry around the ePay ad, and our own history of tone-deaf pieces here at Rice).

It shouldn’t take things boiling over for us to start caring, but that’s also how it usually goes. The movements which generate the most noise are also the ones which tend to spark the most curiosity.

We know that an outspoken, consistent commitment to fighting racism is as needed here as it is in the US. We know Singapore has our own troubled record of systemic racism, denial, and insensitivity.

We’ve seen it in everything from persistently racist stereotypes of minority Singaporeans and black culture in our media, to ‘Chinese only’ job ads, to educational policies which favour Chinese Singaporeans. And for the last two months, we’ve talked about little else but the xenophobia and NIMBYism levelled against our migrant workers.

To this end, if Black Lives Matter, rather than any local instances of racism or xenophobia, is what it takes to keep the conversation going here, then so be it.

If reading about the things white Americans can do with impunity is what leads Chinese Singaporeans to recognise the freedoms we enjoy that minority Singaporeans don’t, it’s still a step in the right direction.

Similarly, yelling at people on Facebook for not showing up for migrant workers two months ago won’t undo their silence. We can’t change how many people challenged racist or xenophobic behaviour in the past, but how many will in the future remains an open question.

What should trouble us is how long we’ve been trying to have the race conversation, and how little movement we’ve made on this.

For years, academics, activists, artists, NGOs, and civil society groups have spoken out against racism in Singapore, and produced thought-provoking work around how race, power, and privilege operate in a local context. (There’s been a groundswell of interest in this over the last few days: a helpful compilation of Singapore-specific learning materials can be found here.)

But while interest in these issues has picked up in the last few years, it’s still largely kept to the fringes. It’s never consumed our local discourse the way Black Lives Matter is doing now in the US.

As my editor succinctly put it, “To speak about racism is to speak about race, and this has always been a no-go zone”.

A large part of this can be attributed to Chinese privilege, and the reluctance of Chinese Singaporeans to acknowledge the benefits we enjoy, or to listen to minority Singaporeans’ concerns, without asking them to sugarcoat their anger or spoon-feed us solutions. (These are mistakes I’ve personally made, too.)

On an individual level, consoling ourselves that we ‘aren’t part of the problem’ because ‘we don’t use the N-word’ or ‘wouldn’t filter for race on dating apps’ is just as problematic. Ignorance, apathy, denial, tone-policing, and gaslighting are subtler, but equally harmful forms of racism.

But Black Lives Matter, like Covid-19, has also exposed the hollowness of Singapore’s comparison culture, and our habit of using other countries’ problems as a mirror to reflect ‘how good things are’ here without acknowledging our own failures.

It does us no good to insist that minority Singaporeans are lucky because they don’t have to worry about getting beaten up by the police, or that our migrant workers should be ‘grateful’ to be here rather than back home or in the Middle East.

All these demonstrate are poor reasoning skills and an inability to accept when we’re wrong. Nothing will change if we continue to deny our individual mistakes and failures of judgement, or the blind spots which exist in our systems and policies.

The pandemic has proven that our lives are more interconnected than we pretend they are, and that there are limits to claiming things are ‘someone else’s problem’. If all roads lead to Rome, Black Lives Matter, the fallout over migrant workers, and our long history of stalled race conversations all lead us to the same conclusion: we have got to do better.

We now have, once again, an opportunity to make good on this.

It was always obvious that we have a problem talking about race. Identifying this was the easy bit. The harder part is what comes next: how to create constructive and lasting change, both in ourselves, and the systems we exist in and support.

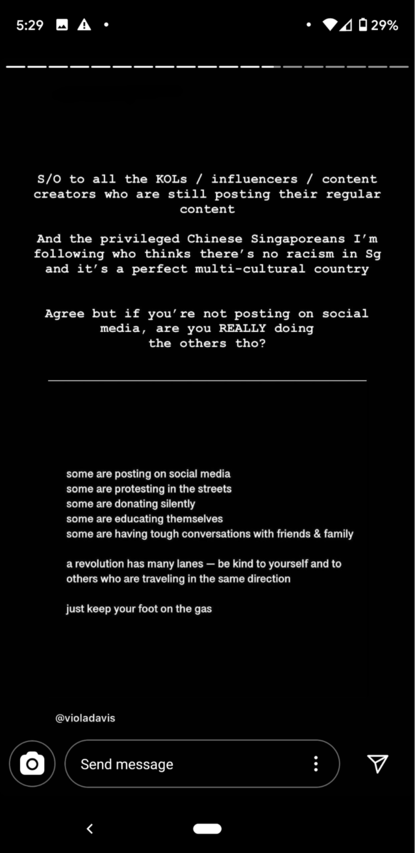

In this, a lot of anger has been directed at the hollowness of social media and armchair activism.

Social media can be effective as a method of raising awareness and generating public pressure. Recently, we saw this with how food standards for migrant workers rapidly improved after activists sounded the alarm on Facebook.

Nonetheless, it’s still the lowest hanging fruit on the tree of solidarity. Too often, social media is a no-risk way for us to feel like we’ve done something without actually doing anything.

There is a whole spectrum of actions in between ‘liking and sharing’ and ‘taking to the streets’ which tends to get lost. This is especially problematic in Singapore’s context, where we often assume that our individual actions don’t make a difference, and resharing something on social media is the most we can do to change anything.

It’s why the events of the last few days have inspired such massive cognitive dissonance, and so many cries of hypocrisy. By and large, social media is the extent to which many of us practice our politics.

Black Lives Matter is instructive for us in this regard. The thrusts of the movement are education—un-learning as well as learning— action, and structural change.

The toolkits on allyship apply here in their own ways. We (especially Chinese Singaporeans) can apply the same intensity to reading works by minority race scholars and writers, and paying our migrant workers (domestic and non-domestic alike) better salaries. We can ask local brands to use models of all races and ethnicities, and stop supporting businesses which don’t share our values.

We can push for better diversity at our workplaces, and ensure that minority-race Singaporeans, migrant workers, and vulnerable communities get a seat at the table. We can donate, fundraise, or volunteer for NGOs, or insist on more accountability from our MPs.

We can insist on more accountability from ourselves.

And we can apply the same intensity to the smallest, most delicate things: to paying attention to individual stories, the ones which get stuttered over or tentatively recounted; the ones which cost so much to say and nothing to listen to.

When the movement first reached Singapore, one of the first, surface-level questions to emerge was ‘should I care about Black Lives Matter’?

There is no reason why we can’t or shouldn’t care about Black Lives Matter. We can and we should, but the logical extension of this is undeniable.

If we can care enough about racism and injustice in another country to make a statement on social media, then this only raises the bar for the things we can change and can control—the racism and injustices present in our country, and which we perpetuate ourselves.

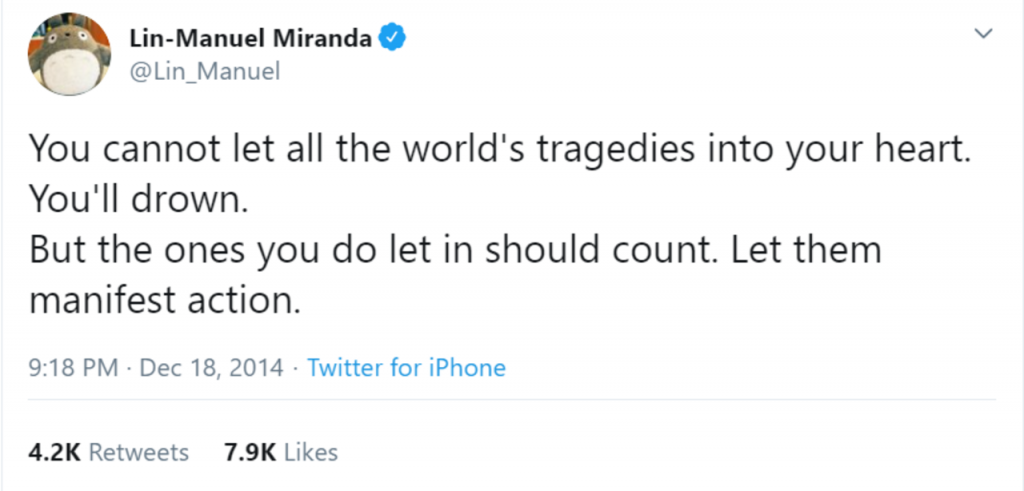

One of the posts which caught my attention last weekend, by the American poet and author Scott Woods, had this to say: “There is no anti-racist certification class … It is a thing you have to keep scooping out of the boat of your life to keep from drowning in it.” There is no way to answer ‘how much is enough’, because we can always do more.

What did you think of #BlackOutTuesday? Drop us a note at community@ricemedia.co.