Top image: SCMP

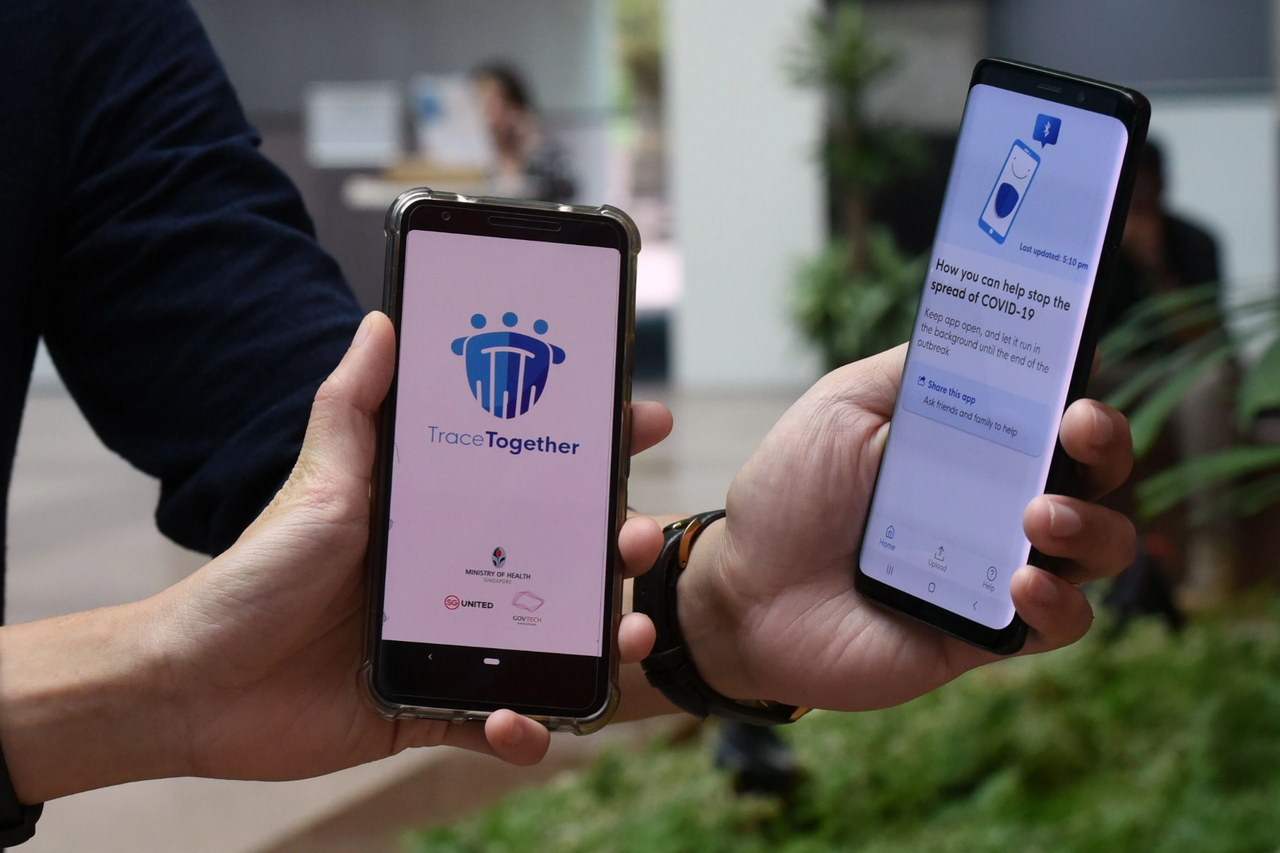

What a start to the year. On Monday, the inaugural Parliament livestream triggered a real-time outcry over the collection and use of TraceTogether data.

Contrary to prior assurances that TraceTogether data would only be used for contact tracing, Minister of State for Home Affairs Desmond Tan clarified that the police are, in fact, legally empowered under the Criminal Procedure Code (CPC) to access said data for criminal investigations. The TraceTogether website FAQ was then updated to reflect this, ostensibly in the interests of ‘transparency’. Cue the first social media uproar of 2021.

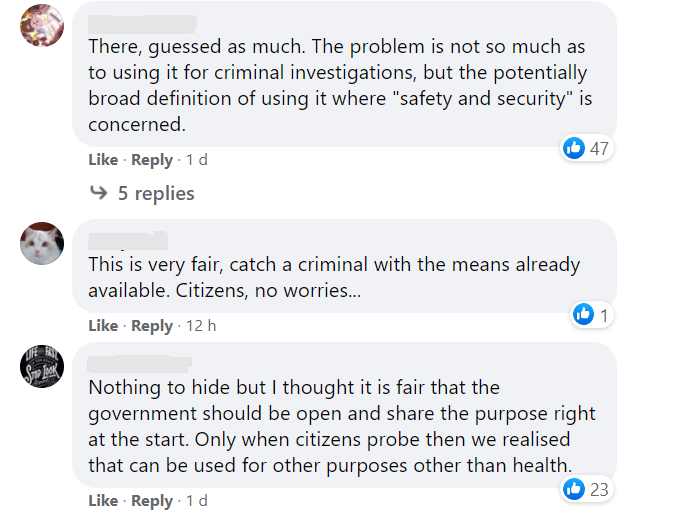

Some shrugged, saying they had nothing to hide. Some responded with “I told you so”. Still others were suspicious, if not livid, about the blatant U-turn. And of course, many more turned to memes.

Whichever camp you’re in, it’s clear that this revelation undermines the extensive efforts to win public support for TraceTogether, and feeds into earlier anxieties that it could be supposedly abused as a hidden tracking device.

To be honest, even with this latest development, it’s probably not worth getting worked up about location tracking. TraceTogether works by detecting proximity to other devices, not location. Expert teardowns of the token last year concluded that it did not have a GPS function and was “unlikely to be a useful tracking device” (though this was at least partially based on assurances that only MOH’s contact tracers would ever see the data)

And as Minister Tan’s comments revealed, the remit of the CPC means that law enforcement is already empowered to access far more useful data, such as SafeEntry records—which, by the way, were also meant to be ‘for Covid-19 purposes only’.

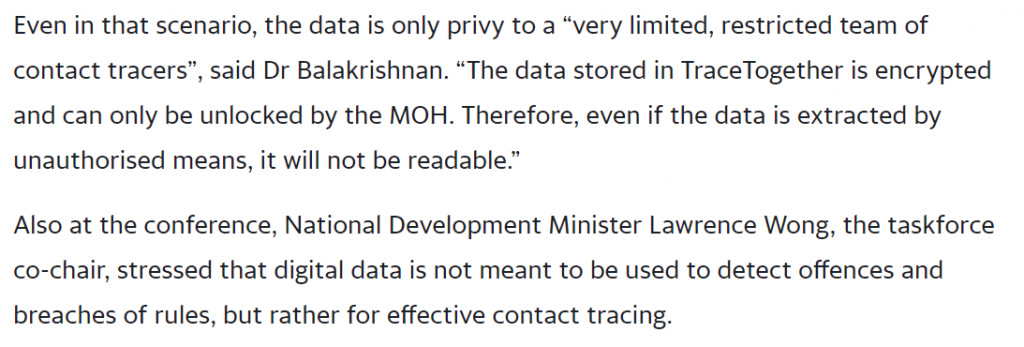

What the clarification does do is raise questions over how exactly the proximity data might become useful to the police, whether there is potential for it to be misused, and what sorts of offences are quote-unquote ‘serious’ enough to trigger the exception.

It invites incredulity as to how Minister Balakrishnan could have overlooked the CPC during his PR offensive for TraceTogether last year. And it encourages anxieties over the inconsistencies and back-pedalling in government communications.

These are all serious issues, but not the real source of public ire; nor is there any evidence that this was a deliberate conspiracy to mislead the public. What this episode really invites us to consider is a question of trust: whether the government can be relied on to keep its word, with no catch involved.

Optics-wise, it’s a terrible look: a communications blunder that could have been easily avoided, and a breach of public trust for no good reason.

As far as rights concerns in Singapore go, data privacy and surveillance have seldom been a priority. Last year’s PDPA consultation went largely ignored by the public; many of us—myself included—remain oblivious to the sensors, cameras, and GPS devices #disrupting and #innovating and #connecting our way into Smart Nationhood (like the time it was proposed to embed our lamp posts with facial recognition technology). Meanwhile, legislation like the ISA casts a long, dark shadow over our willingness, historically, to make trade-offs between civil liberties and national security.

By these standards, the hostility towards TraceTogether, even prior to this incident, was unusual.

Last year, the announcement of the token was greeted with a petition in protest, garnering over 50,000 signatures in a few days. Following months of will-they-won’t-they coyness—Minister Vivian Balakrishnan had previously said that TraceTogether would be “voluntary for long as possible”, but stopped short of a definitive statement—October’s announcement that TraceTogether would eventually be mandatory in certain circumstances raised enough eyebrows for MP He Ting Ru to bring it up in Parliament. And a Blackbox Research survey from last month showed that 32% of Singaporeans doubted that TraceTogether data would only be used for Covid-19 monitoring.

TraceTogether, in other words, was always a hard sell. But had the government been upfront about the CPC caveat last year, chances are that the public, despite its unease, would have understood.

Unfortunately, thanks to its own insistence that the data would be used for contact tracing and contact tracing only, people are not only uneasy, but outraged that the government has gone back on its word.

The irony is all too keen, given how the successful implementation of TraceTogether relies on mutual trust between citizens and the state. Mass adoption of the technology—enough to trigger Phase 3—was arguably earned, at least in part, on the expectation that the government would honour its promises. Nor is it reassuring that despite the lessons of last year’s GE, public goodwill appears to have been taken for granted.

What does this mean going forward? For one, potentially more road-bumps to realising our vision of having “everyone, everything, everywhere, all the time”. (I’m not kidding; this is the actual plan underscoring our transformation into a living dataset).

This debacle suggests that distrust might colour the way future data-collection practices are viewed. The fears around a slippery slope are not unjustified: is there a clear line that the government will not cross when it comes to using our personal data?

Most of us understand there are trade-offs to be made in any policy decision, and realise that in some instances, the potential benefits to public health or national security may outweigh the costs. But an informed choice means those costs should be declared to begin with.

More troubling is how episodes like this one encourage cynicism towards governance.

It behooves no-one to reach a point where we believe that the government is flying the plane and we’re all just strapped in for the ride. After all, if we suspect that back-doors and hidden T&Cs will always be introduced after the fact, why listen in the first place?

Data might be the commodity of this century, but public trust is just as valuable an asset. Since Monday’s revelation, Ministers Shanmugam and Balakrishnan have been in full-on damage control mode, giving more assurances that the TraceTogether data is only retained for 25 days and that law enforcement must exercise their powers with ‘the utmost restraint’, giving the example of how TraceTogether data was used to solve a murder case.

It remains to be seen if, this time, words will be enough. Or maybe we’ll just have to wait a couple of months for another clarification.