Char Kway Teow is a famous hawker dish that is ubiquitous in Singapore, but it is not a Singaporean invention. It has roots in Chaozhou, in China’s Guangdong province, and was believed to have been brought over by Teochew immigrants. In fact, the dish is popular across Southeast Asia, with notable variants in places like Penang.

But ask any Singaporean and they would describe some traits that define the dish locally: the ratio of flat noodles to yellow noodles, the dark colour, the sweet and savoury flavour, the inclusion of ingredients like beansprouts, eggs, cockles, and lap cheong (Chinese sausage). Singaporeans have been called foodies and, indeed, the local hawker and food culture has been celebrated as a source of national pride, going as far as to be nominated for recognition on the Unesco Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Director Tan Pin Pin understands this as she opens her film To Singapore, with Love with a man living in London cooking Char Kway Teow.

“It’s partly how to cope when you’re abroad, not to feel defeated. You still try to cook your own Singapore food,” he explains as he stirs the wok full of noodles and prawns.

To Singapore, with Love grapples with dark spots in Singapore’s past, with events whose historical truths have been hotly contested and remains a difficult conversation topic, a conversation that was avoided in 2013 when the release of the film was banned in its own country. Singapore’s Infocomm Media Development Authority justified the ban by stating the film gave “distorted and untruthful accounts” and would “undermine national security”.

A Human Experience

In an interview with Pin Pin, the director explained how state archives for historical events recounted in the film had not been released, so she had only first-hand accounts and newspaper reports to go on. That is not to say these accounts are not factual or worth considering; they certainly are. Even so, the film is not very interested in verifying this time in history.

It doesn’t linger on investigating the actions of the government or the supposed conspirators in those operations. It is not a polemical film asserting who was right and who was wrong. Instead, it is a humanist film that lends voice to people who have been silenced.

Humanism is a broad way of thinking that can stretch into philosophy, the arts, and humanities. Its basic principles include human reason, ethics, and justice, often looking into individual human experiences to draw meaning and uphold human dignity. True to the humanist tradition, To Singapore, with Love recognises its subjects’ basic dignity to let them speak, lingering on their experiences, thoughts, hopes, and dreams. Besides interviews, we see these people live their daily lives: they cook meals for their families, they interact with colleagues in their workplace, they play with their children, they reminisce about the past through old photographs and possessions. What’s most telling about these people, and what informs the film’s title, is that they long to return to a country in which they are being persecuted. All of them still love Singapore.

In a 2014 statement about the film on Facebook, Pin Pin described it as a portrait of Singapore seen from an external view—from exiles recounting their memories living in Singapore, and literally as the film closes with shots looking at the island from across the causeway in Johor Bahru. The film is as much about these people as it is about the Singapore People who make up the island nation.

Notions of national identity are raised when these exiles are forced to live abroad—in one instance, Ang Swee Chai recounts being questioned by an Internal Security Department officer who warns her of life in exile, that she would be nobody overseas—and the film interrogates the idea of the nation to ask “What is Singapore?” It is a searching question that our supposedly young nation still asks itself today (was Singapore born in 1965, 1959, 1819, 1299 or some other date?). Without giving any clear answers, the film gives us some clues through these stranded Singaporeans.

The first clue is delivered right from the opening of the film. Singapore has a self-professed love for food indulging in a diverse range of local delicacies. This food euphoria is emblematic of a shared culture grown within Singapore; it came about as a result of the intermingling of various peoples who built a community together.

Nations are constructed by its people and are malleable entities that change with the tides of history. This is evident where civil conflict is rife as communities of people band together or resist one another. What binds these communities together is the notion of the nation which can be broadly split into a political domain regarding the political system that governs the community, and an ethno-cultural domain that is built from shared language, ethnicity, tradition, culture, religion etc.

Given Singapore’s multiracial demographic, her national identity isn’t built based on race but on other cultural characteristics like food, Singlish (an invented vernacular based on the assimilation of languages from different ethnic groups), and being Kiasu (a fear of losing out). Though Singaporeans like to claim these traits as uniquely Singaporean, they are also found across Southeast Asia and other diasporic communities.

For instance, Malaysia has many similar versions of hawker delights and ways of speaking. Nonetheless, Singaporeans have adopted these traits as their own through invented traditions and shared living experiences.

My Family, My Home

Traditions are the stuff of families; habits, games, and rituals are passed down a familial lineage to create a strong sense of belonging to one’s family. What the people in To Singapore, with Love miss most is their families and this is explored through Swee Chai and Juan Thai.

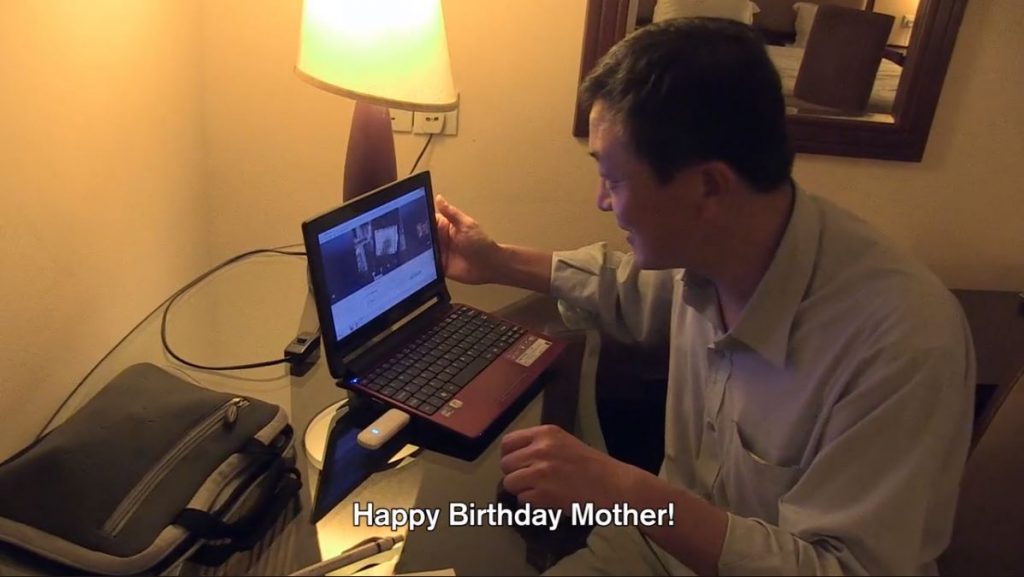

Both often think about their mothers—Swee Chai ponders the heartache her mother must have endured for her daughter’s sake, and we see Juan Thai celebrate his mother’s birthday remotely through Skype. Swee Chai doesn’t have children, fearing their safety if anything happens to the exiled parents. Juan Thai also shared this fear but eventually settled down with his own family in his 60s. The love he has for his children is moving—he calls it a wonderful thing that he hopes all Singaporeans can experience. Despite being born and raised in London, he still wants his sons to be Singapore citizens, to grow up and serve Singapore’s conscription army; the connection to his homeland extends that deep.

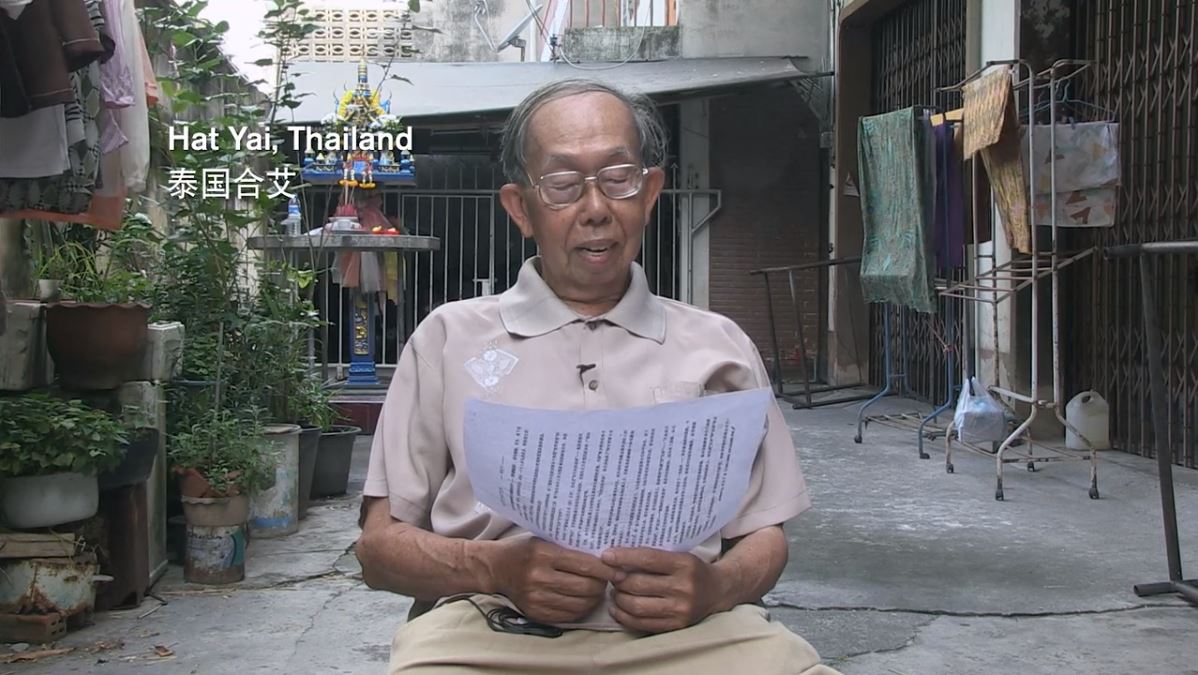

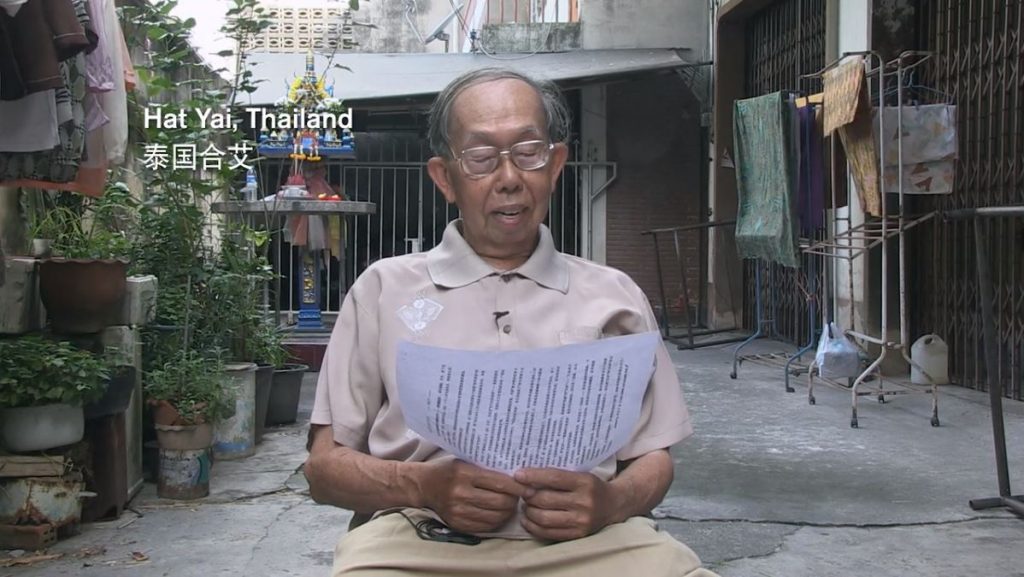

Swee Chai still remembers the exact address of her childhood home in Serangoon after decades away. Others like Chan Sun Wing, who now lives in Thailand, also remembers his homeland fondly; in a poem, he cites the many roads and sites in Singapore that were stomping grounds in his youth.

Connections to space are explored in geography, and for a humanist film that explores the lives of people, it is useful to turn to humanist geographer Yi-Fu Tuan for insight.

Tuan is famous for popularising the distinction between place and space; put simply, place refers to the physical geography in which we live, and space refers to the meanings attached to the place by our individual experiences of the place. Nations are such spaces where meaning is constructed and associated with the geographical land by communities that reside in them. This also suggests that the nation is an unstable category that can be changed based on the individual’s experiences.

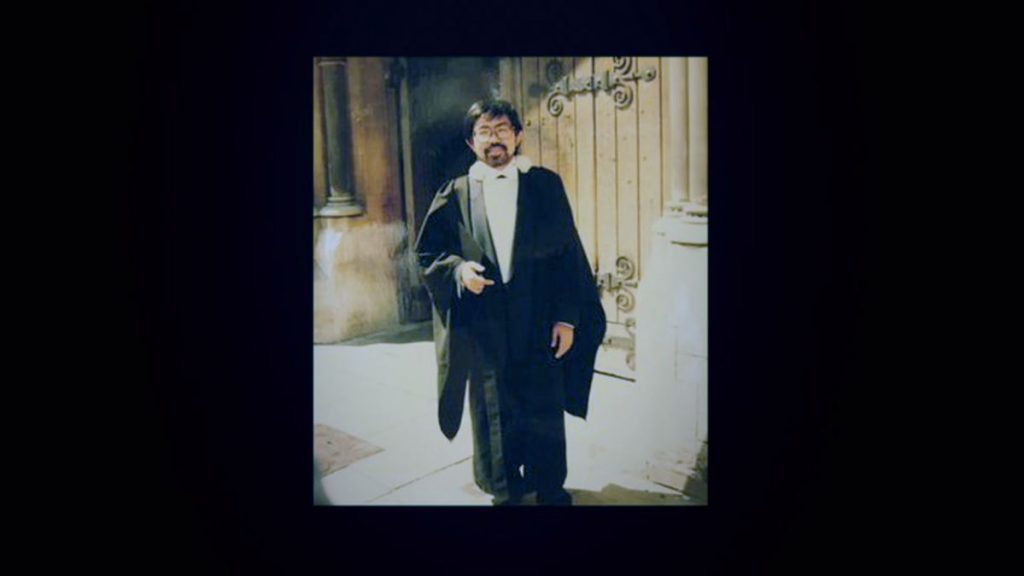

The ideal of the American Dream, for example, embodies such a shifting concept of national identity where even immigrants can call America their new home. Though their circumstances differ wildly from hopeful migrants, the people in To Singapore, with Love have also lived in different countries and built formative experiences there. Juan Thai started his own family in London, Swee Chai had personal moments of revelation attending demonstrations held in London, Tan Wah Piow has set up his own law firm in London. Yet, they still have strong connections to Singapore. Taking a humanist perspective, it is easy to see why.

The former members of Barisan Socialis and Communist Party of Malaya seen in the film have all been part of key historical moments in modern Singapore’s formation. Their personal experiences of struggle are the same struggles that formed Singapore. Political ideologies and historical “truths” aside, these people grew up in and have a close affinity for their homeland, taking part in struggles that have been pivotal moments in their individual and communal histories.

In the same poem by Sun Wing, he tells of his experiences during the Japanese Occupation and Singapore’s independence from British rule, cheering ‘Merdeka’ at the old Kallang Airport.

The shared history of people and country is also seen in the other interviewees; former student leaders and activists like Juan Thai who advocated the preservation of ethnic languages and Wah Piow who campaigned for worker rights, all of whom took active part in shaping the trajectory of their country in the hopes of bettering society. These people were present at the birth of the Republic of Singapore, they were the Merdeka and Pioneer generations of Singaporeans, their personal histories enmeshed with the nation’s history.

Much in the same way Singaporeans today belong to the nation by sharing historical moments—living through national hardships like economic recessions and health pandemics, or celebrating victories in international sports competitions—the people in To Singapore, with Love have a deep sense of belonging to Singapore by their lived experiences in the nation that remains their home.

Who is Singapore?

As Singapore, and the rest of the world, continues to live through the Covid-19 pandemic, nations are shying away from globalised networks and turning inward. We, in Singapore, have celebrated some triumphs against the pandemic while other problems have surfaced that test our ideas of community and who has membership to the country, casting light on this very important question: “What is Singapore?”

In the same 2014 statement on Facebook, Pin Pin said she made To Singapore, with Love because she wanted to better understand Singapore.

Indeed, after viewing the film, a response to “What is Singapore?” can be more clearly articulated, but it is a question that cannot be definitively answered. It needs to be continually discussed and reimagined, it needs to include voices of people who have been marginalised but have as much a stake in the national conversation as any “regular” Singaporean. Singapore has historically been a place that supports diversity, built by diversity, and must continue to thrive on diversity.

The film ends with an original song by the late Francis Khoo; it is a folk song titled “Anak Pulau Singapura” and, like all good folk music, it is simple but carries heavy wisdom that serve us well to remember.

I am a child of my island, the fairest island by far

Selatan tanah Melayu, anak palau Singapura.

(In the south of the Malay land, the child of the island, Singapura)

Inilah riwayat kita (This is our story); we have a story to tell you

Of how we worked hard to make this part of our tanah air ku (motherland).

Our fathers came from the mainland and other lands far away.

They made the old Sri Temasek the thriving city of today.

Dari dulu sampai sekarang, siapa yang membina sekolah dan mendirikan bangunan?

(From then until now, who built schools and erected buildings?)

Ialah semua rakyat kita (They were built by the people).

So as a child of my island, I know the ink is not dry

Our story’s still yet unwritten, today I’ll join my people’s cry.

What does it mean to be Singaporean? Tell us at community@ricemedia.co.