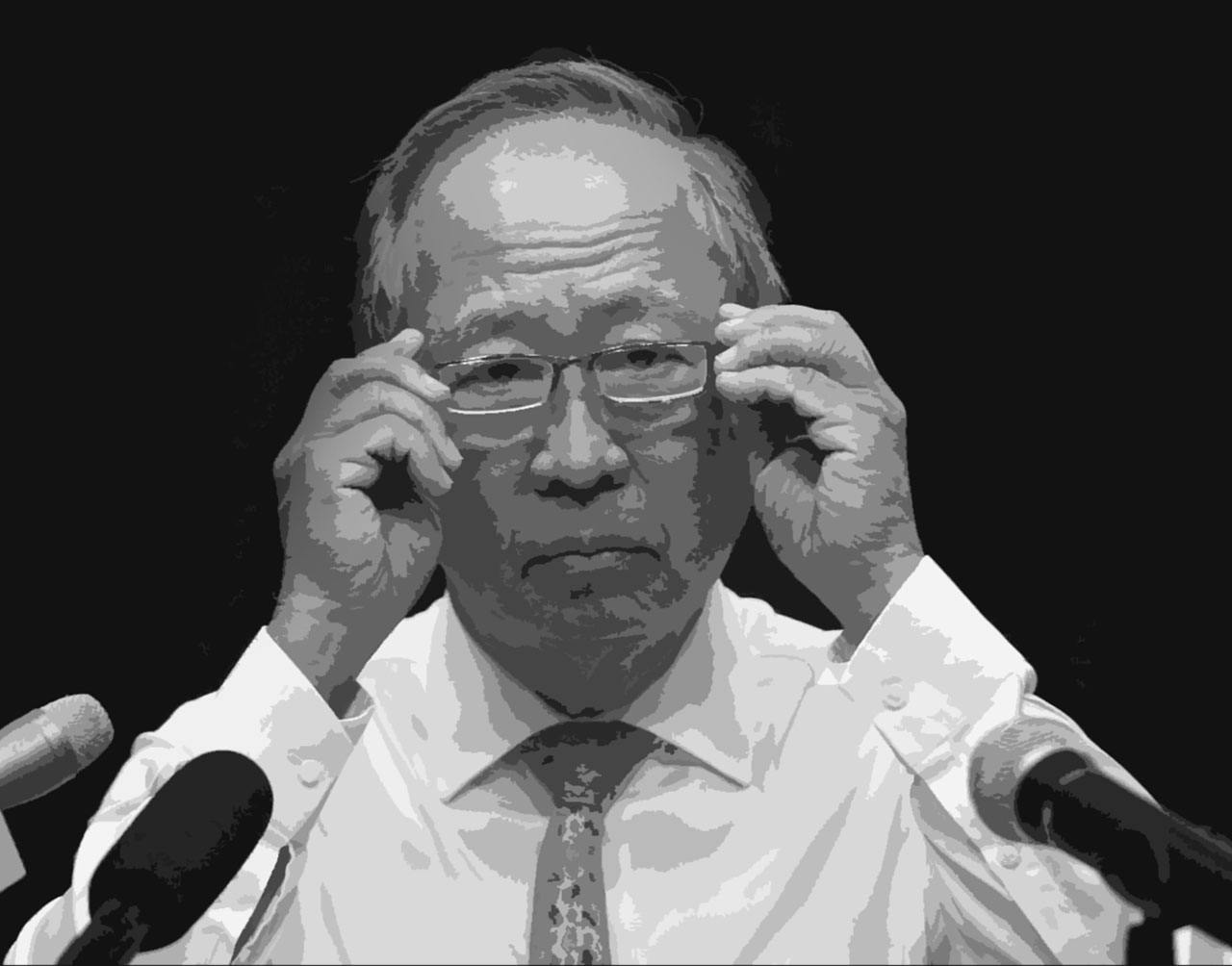

You probably do not care about Tony Tan. In fact, many of us will probably only remember him as the subject of a long-standing Internet meme.

With his neatly combed white hair and dark-rimmed spectacles, he looks exactly like Colonel Sanders. And it’s not a compliment – the term “KFC president” is often used in jest to cast scepticism over President Tan’s ability to remain politically independent as the head of state.

As his presidency draws to a close, many view Tony Tan’s presidency as a largely unmemorable one, with some even claiming that he has done “nothing” for the country. In a video interview with Mothership, this year’s presidential hopeful Farid Kahn visibly struggled to cite President Tan’s contributions.

To be fair, the limitations to the office’s powers makes it difficult to create an extraordinary presidential legacy. Yet, the late S R Nathan and Ong Teng Cheong seem to be remembered more fondly by the public.

So why do we feel so indifferent towards Tony Tan’s presidency?

Back in 2011, Tony Tan had won with a slender margin of 0.35 per cent – just over 7,000 votes – over the populist candidate Tan Cheng Bock in a four-way contest. But with the first-past-the-post system, it meant that Tony Tan was elected into office without even securing majority support from the people.

Given Tony Tan’s previous ministerial appointments, including Deputy Prime Minister, many Singaporeans would have felt aggrieved at that time that the system had favoured a government-backed candidate who would be, in their view, docile.

In other words, they wanted President Tan Cheng Bock, who they thought could truly represent their interests in the event they disagreed with a governmental policy or decision.

The Constitution of Singapore confers on a president “discretionary, custodial power” to block but not initiate decisions or policies in several areas, most important of which pertain to protecting Singapore’s reserves as well as key public-sector appointments.

Tan Cheng Bock, a former PAP MP himself who seems to not toe the party line, could theoretically force the government to exercise more discretion in policy-making. This role of the president was expanded in 1984 as a contingency in the event that an Opposition-led “rogue government” were to be voted in. As the late Lee Kuan Yew explained in his 2011 book Hard Truths to Keep Singapore Going, “If you change all the permanent secretaries, military chiefs, commissioner of police, heads of statutory boards, then you’ll ruin the system. For five years, the President can prevent that. And our past reserves cannot be raided.”

Tan Cheng Bock was and still is the hero that the city-state needs

To them, Tan Cheng Bock was and still is the hero that the city-state needs. And as we are on the cusp of electing a new president, the spectre of Tan Cheng Bock still looms large.

Reserving the Presidential Election for only members of the Malay community has been a controversial decision. Dr Tan and his supporters feel that this was a deliberate move to bar him from riding the wave of anti-PAP sentiments to run for president again – hence the witty pun “Tan Cheng Block”. (His fate was sealed yesterday when the Court of Appeal threw out his appeal against the High Court’s dismissal of his application contesting the legitimacy of the reserved election.)

So for yet another six more years, it seems Singaporeans have been denied the right to vote for the best presidential candidate, as Dr Tan’s supporters would argue.

—

The past year, marred by relatively slow economic growth and major train breakdowns that seem to be an incurable disease, needs a positive light. Yet the bread-and-butter political issues that had worried the public were not addressed at this year’s National Day Rally, further fuelling discontent that the government is consciously shying away from glaring problems at hand or, worse still, beginning to lose the plot of running the country in a post-Lee Kuan Yew era.

Thus, it has become easy to fantasise about what Tan Cheng Bock, a man who is not afraid to speak his mind, could do in office. “President urges stricter penalties for train breakdowns” could possibly be a reassuring newspaper headline in a groupthink climate, courtesy of a man like Tan Cheng Bock.

Unfortunately, that is and will remain a fantasy in Singapore’s political landscape. The idea of a President Tan Cheng Bock as the highest-placed alternative voice in Singapore is still a construct of wishful thinking. This has led many to disregard the fact that the Constitution would ultimately put the brakes on Dr Tan’s drive to be the people’s prime check and balance on the government.

The yearn for change is fervent, hence many have chosen to be indifferent or even overlook the qualities and contributions of Tony Tan, holding out for a Singapore in which Dr Tan Cheng Bock would be President.

There will be a new occupant of the Istana seat come September. But behind him or her, the hazy apparition of a President Tan Cheng Bock still hangs, along with what could have been.