My childhood at the turn of the millennia played out under the tyranny of adults who much preferred the stick to the carrot. Did I deserve it? Probably. Did it also leave me with a deep seated fear and indelible distrust for authority?

Ehh … maybe?

These days, we’ve started turning away from hitting our children as a form of discipline. Society at large is starting to see that violence may not be the optimal solution for imparting life lessons, even if it might be effective in some cases.

At the same time, being a teacher is an often thankless and grueling job. Imagine handling multiple 30-student classrooms of bratty, screaming kids. Preparing for lessons and the marking thereafter—inclusive of chasing for homework to be handed in. Being in charge of CCAs and organising events, outings; every possible opportunity required to deliver a holistic, world-class education.

And there’s the parents. An additional layer of insufferable kiasuism, with incessant demand after demand. But parents and teachers don’t have to be diametrically opposed.

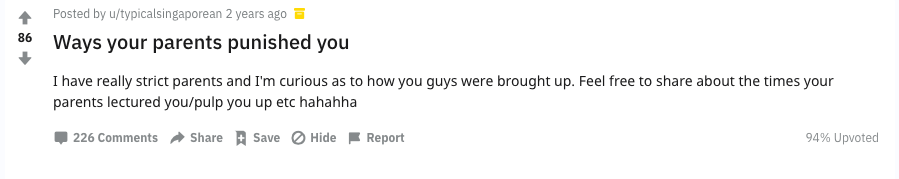

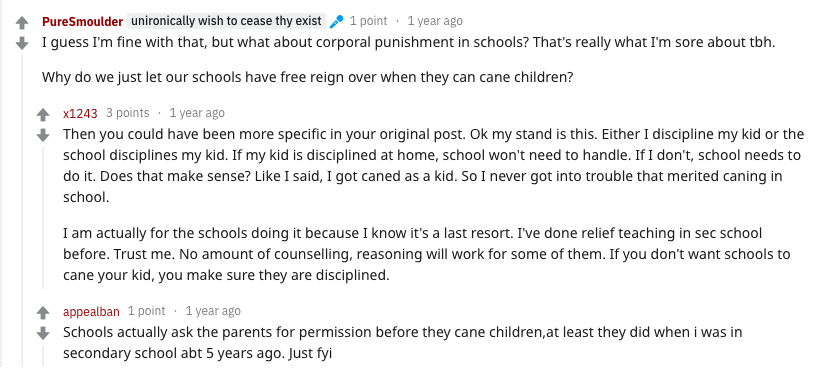

How can we reconcile the difference between discipline in a household and the classroom? Should parents empathise with the plight of teachers—that juggling between dozens of students might require harsher measures? Should corporal punishment make a comeback so that teachers can more easily keep students in line?

I spoke with two parents from different generations about whether teachers should hit students as punishment.

Harsh discipline might have been the way of the older generations, but Jolene realised that using violence was more often than not extremely emotional. The facade of the cool disciplinarian carrying out ‘operant conditioning’ fades away, and what’s left is simply lashing out in a fit of rage.

Seeing her life experiences reflected on the screen showed her how such violence takes a mental toll on both the punished and punisher. And that’s not including the physical pain felt by a child.

“It always broke my heart when I had to punish my children,” she says. “Just as it’s uncomfortable to think about it now.”

There’s a pained look in Jolene’s eyes as she admits regretting many of her actions in the past, that she should have been more mindful in handling discipline.

“We’re all so stressed nowadays, being piled on with complications from work, personal life, societal expectations,” she says. “The potential of taking that out on a child—who has their own problems and anxieties—through force is a deal breaker for me now.”

So when I ask about teachers and their disciplinary methods, she’s adamant that they should not hit children because “parents know their children best.” The stress and undue burden that teachers have serves as even more reason for them not to.

“If a parent like me can’t always do it right, what makes you think a teacher can?” Jolene asks.

“As a mother, my children are my flesh and blood. There’s little that might prevent a teacher from crossing boundaries in the heat of the moment.”

She concludes that such forms of discipline should stay strictly under a parent’s purview.

I proceed to challenge her: what if parents are negligent, or simply unable to spend time to properly educate their children? With all the stressors of modern working life, some parents might just not have the capacity to raise their children in an ideal way.

Jolene still shakes her head, and insists it’s not the teacher’s job to parent children. To that end, we should stop treating teachers like therapists, enforcers, and nannies. Yes, the job scope does overlap with some of these areas, but they are first and foremost educators. There should be an adequate system of support; of other specialised personnel to deal with the myriad of challenges teachers have to face.

“If I did learn my lesson from the first stroke, I would not have needed the second!”

Rather, it was the sit-downs in the discipline master’s office, and the long serious talks telling Leon to wake up his idea that spurred him to improve.

At 27-years-old with a 2-year-old daughter, Leon is still figuring out his principles for parenting. But on the question of whether teachers should use corporal punishment, his personal opinion is no, because it doesn’t work.

We hear horror stories of rambunctious, apathetic, and sometimes even cruel students committing transgressions. And we think that maybe all they need is a good whack to drill some sense into them.

But does the pain and shame from hitting students really prevent them from acting up again? Do education institutions reinforce their authority through corporal punishment, or does it serve as further cause for rebellion? Do public canings deter other students, or is it a popcorn filled spectacle for us to revel in schadenfreude?

Beyond its ineffectiveness, Leon’s denunciation is because he believes in leading by example.

“If my girl is being defiant and I respond by hitting her, she might grow up to be violent when others defy her. Because that’s what her father taught her to be,” he tells me. “I do not want my daughter to grow up believing that violence is the way.”

Clearly, parents and teachers are the first authority figures children interact with—so how should they be working together?

Leon stresses that both parties have a shared responsibility for imparting values to children. But parents have to do the emotional heavy lifting because compared to teachers, they are immutable. Much more respect will be deferred to them, and a teacher’s reach is ultimately limited.

In light of this, Leon agrees that teachers have to be firm and loud to command attention from unruly students. But there’s a fine line they have to tread to be careful that they don’t overreach, where discipline regresses into abuse.

He’s careful not to endorse my tacit suggestions of ruling by fear, but many believe this is an effective compromise. After all, if the argument for corporal punishment is that some young kids can’t be reasoned with, surely intimidation is a better alternative than physical violence.

Ultimately, Leon believes that parents and teachers have to be independent together: each with their own defined roles, but working in concert. There have to be channels of communication—in moderation—but teachers should be trusted to deal with school matters because it’s their jurisdiction.

“You don’t try to stop or restrict them from carrying out their duty,” Leon asserts. “When my daughter is home, I’ll take over.”

After all, that’s how Leon’s mum dealt with him—whenever he got into trouble in school, she let the teachers handle it. And it was the care and concern from his teachers that helped shape him into a more sensible and mature adult.

So yes, Leon got hit and turned out okay. But it had nothing to do with the hitting.

In an institution with strict social roles and codes, where we’re faced with the banality of the masses, it’s easy to dismiss each other. To settle on quick resolutions that might do more harm than good.

But the trifecta of students, parents and teachers would do well to remember each others’ humanity. Students and parents can be obnoxious gremlins deserving of Haw Par Villa’s many courts of hell. But they’re also you and I, people who are stumbling their way to a semblance of a dignified life. And despite the selfless nature inherent in many teachers, they can be little shits too.

We might really want to smack each other. But if we want to be recognised as equals—complex humans with differing circumstances—should we consider staying our hands instead?

If you’re tired of attending parent-teacher meetings, you can always write to us instead. Tell us your thoughts about spanking at community@ricemedia.co.