This post was first published Oct 17 2019. Top image: OnePeople.sg / Facebook

Hi, yet another Chinese person here. I know it seems ironic that I’m writing about the fear of speaking up, given that I work as a journalist, but please bear with me.

If you’re a Chinese person reading this, you probably (hopefully) already know that race and racism have been all over the news lately. Maybe you’ve read some commentaries or seen some posts that went viral. Maybe you’ve had some thoughts about these things yourself.

ADVERTISEMENT

Maybe you’ve sounded them out, but it’s more likely you haven’t. Maybe you think the Nair siblings were justified but don’t really want to have this argument with your friends. Maybe you get that brownface is wrong, but don’t want to get into a fight about this. Or maybe you just don’t understand why everyone is so angry.

If any of this sounds familiar, this piece is for you.

Talking about social justice issues, whether online or in person, is something a lot of people find intimidating (even for many of us at RICE, yours truly included). It can seem impenetrable, as though you need to grasp terms like ‘microaggressions’ or ‘intersectionality’—which are academic in origin and have yet to enter mainstream use—to participate.

(Just to get this out of the way: this is entirely separate from writing such terms off as ‘American liberal SJW language’. Debates about cultural context are one thing; immediately deriding something as ‘irrelevant’ because it originated elsewhere is another, and on that point, no one’s ever dismissed megachurches, self-care, or McDonald’s for being American exports. Using ‘American’ or ‘the liberal West’ as a catch-all boogeyman to dismiss unfamiliar or unpalatable ideas is sloppy reasoning, so let’s leave it at that and move on.)

But more than issues of accessibility, these topics are nuanced. They’re touchy. They invite strong opinions and involve intense debate and contention.

And if there’s anything that makes Singaporeans recoil, it’s getting involved in anything with the slightest risk of confrontation.

This is especially so if:

a) you hold a view that you think might be controversial or ill-received,

b) have a question which you suspect could be a stupid one, or

c) someone says something you don’t agree with or understand.

Maybe you don’t feel you know enough to weigh in or aren’t sure you can articulate yourself clearly. But more often than not, you’re scared you’ll say something wrong, a heated debate will ensue, the online mob will come after you with pitchforks, and everything will go to hell.

So you just stay quiet.

At the risk of sounding like an apologist for inaction—more on that later—we can, I think, acknowledge that few people feel confident enough to talk about race, online or offline. Much as articulating one’s thoughts is a skill like any other (i.e. one which develops with practice), it’s easy to be confident when you believe in what you’re saying 100 percent; it’s less easy when you don’t know if you’re right.

ADVERTISEMENT

This might seem like an odd point to focus on, but speaking up—whether to ask questions, challenge a view, or make a point—makes all the difference between being passively not-racist and actively anti-racist.

The former allows discrimination to continue through complicity. The latter refuses to enable it and consciously tries to put a stop to it through action. It’s the difference between silently squirming when your uncle jokes about ‘Indians and their funny accents’, and asking him why he thinks this is funny.

For this reason, if we ever want to move forward, we cannot afford to keep discussions around race (or class, or sexual orientation, or any kind of social issue) an arena where 5 percent of people slug it out, and the remaining 95 percent watch in intimidated silence.

To this end, it’s worth exploring how activism can be effectively carried out and how people can be convinced to join in the conversation. But there is a fine line between asking how this can be achieved and using excuses that social justice is ‘inaccessible’ or ‘intimidating’ or ‘for Western-educated liberal elites only’ as an excuse for inaction.

Right now, we (by which I mean any kind of majority group; yes, I do mean Chinese people) do far too much of the latter.

For starters, there are many routes to learning about racism and social justice—and none of them require a ‘liberal Western elite education’.

“There are a ton of free resources out there and that’s what I learnt from before I left Singapore,” Ruby Thiagarajan, an activist and the editor of Mynah magazine, tells me over text.

She attended The School of the Arts (SOTA) before going to university abroad, but her ‘awakening’ began before she left Singapore or encountered such topics in school.

“My parents aren’t activists, and they have no liberal arts or humanities background, so I don’t think I got exposure to it at home,” she tells me.

“Maybe some people discover their interest for social justice while in the arts and humanities, but for me it was the other way around. I was interested in social justice issues before I entered SOTA. It was a great environment to explore these things, but it definitely wasn’t a bubble.”

She credits watching Live 8 on TV as helping catalyse the realisation that she cared about social justice issues, from which she moved on to “clicking around on [her] own” and subscribing to Reddit boards like Two X Chromosomes. While at university, she started a campus feminist discussion group for participants to explore topics in a non-judgemental environment.

But much as a university education (particularly in the arts, humanities, and social sciences) encourages the study of such issues, it’s by no means a prerequisite for taking an interest in them.

ADVERTISEMENT

There is now so much material online—commentaries, videos, news articles, social media posts, and the like, with views from all ends of the spectrum—that no one (short of being in a decades-long coma) has an excuse for not having encountered such topics. Between those and offline avenues, like talking to friends, there are more than enough resources for anyone to take charge of their own learning.

Take Visakan Veerasamy, whose plain-spoken commentaries you might have seen floating around: “I didn’t go to uni, just picked up the language organically from conversations around me. Twitter/Facebook, friends, news, etc … Anything I wasn’t sure of, just Google lor.”

In other words: No, not having formally studied these concepts is not an excuse.

There’s also no need to belabour the point that social justice terminology can be inaccessible. It’s true that terms like ‘intersectionality’ can be alienating, and conversations around social justice should avoid academic language and be had as plainly as possible.

This being said, Ruby explains, “There’s never been a rule to say that conversations around social justice need to involve big words or academic concepts. Some people do, and they’re usually writers or scholars and they have a place in the discourse, but nobody is asking for everyone to be part of that world.”

(Or as Visakan puts it, “Don’t talk like some intimidating, condescending smartass.”)

But ultimately, to criticise minorities and activists for not being more convincing is to miss the point—and it’s a mistake I made myself, in the course of conceiving this piece, until Ruby and Visakan showed me otherwise.

Discussions about communications strategy are one thing, but it’s essentially victim-blaming to say that racism persists because activists are not making their case more persuasively (or ‘nicely’). It persists because people don’t care enough to do something about it.

Social justice, at its heart, is grounded in the belief that no one group—whether based on race, gender, sexual orientation, or any other marker—is better than another, and that everyone deserves fair and equal treatment.

It’s something everyone has an interest in. The view that it needs smarts or special resources or a Western university education or exceptional confidence to participate in it is not only flawed, but dangerous. As long as majority groups use these as excuses for our own spinelessness, nothing will ever change.

Racism (and to that end, all forms of bigotry) is a binary: you either believe that all racial groups are equals, or you do not. There is no ‘in-between safe space sideline’, and we cannot let ourselves be fooled by the illusion of neutrality.

It’s true that people rarely behave in a manner consistent with what we think, and for this reason, racist behaviour exists across a spectrum of harmfulness (although it all remains, fundamentally, racist). But just because there is no middle ground in racism doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to find common ground for conversations about race.

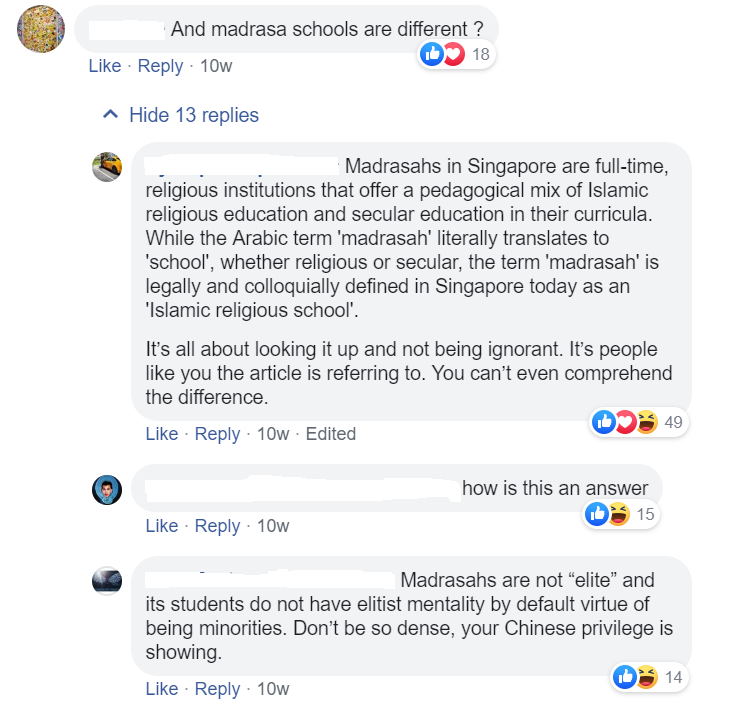

Part of this involves not shaming people for ‘not getting it’ or refusing to engage with contrary views, so long as these are presented in good faith. Going, “It’s 2019, why aren’t you with the programme yet,” only makes people feel defensive.

Nor, for that matter, can we afford to rely on empathy alone. It does wonders, but it is not a miracle pill. Imagination—even when bolstered by good faith and the genuine desire to place yourselves in someone else’s shoes—cannot bridge all gaps in lived experience.

The only way forward is to learn to speak up.

If we want a more equal and respectful society, all of us—but especially, especially, Chinese people and any kind of majority group, given the power our positions give us—need to get over our allergy to hard conversations. We need to ask questions, even if we’re afraid to ask them. The core of racial harmony, that venerated ideal, is not tolerance: it is understanding, and the only way to achieve it is through reflection and participation.

The onus is on majorities to educate ourselves, initiate conversations, and tease out our own assumptions and biases. Importantly, we need to move beyond that to encourage other people—even our friends or loved ones or parents—to confront theirs too. Privilege is naturally blind to its own existence, and as such, a Chinese person will probably never recognise the advantages they hold until someone else explains this to them.

There are so many ways this can manifest, and none of them needs to be hostile.

For example, if you’re looking to talk to your parents about race, a good place to start could be bringing up examples of casual racism in conversation as and when we encounter them, and ask what they think of it. Say, a rental ad which says, “Indians not allowed“.

If they don’t think this is problematic, ask why. An answer derived through mutual reflection is always more meaningful than one that’s been spoon-fed. Conversely, if you think the ad might be justifiable, air your view. Ask a non-Chinese person if they agree, and be open to what they have to say.

To this end, as my colleague Grace wrote, we need to accept that we will misspeak. We will make mistakes, and we will be corrected. And like any process of correction, it is not always going to be comfortable or gentle—but fucking it up is how we learn how to get it right.

Fear is not a valid reason to justify inaction. There is no excuse for inaction. We’re not in school anymore, and we can’t look down at our books when the teacher asks a question and hope that someone else supplies the answer. We cannot be so afraid of failing, or being criticised, that we don’t even try to do what’s right.

As Ruby put it, “If I end up being wrong because I didn’t know enough about the issue or I was ignorant to the needs/concerns of a group I didn’t consider, then it becomes a learning experience for me. I think that when you genuinely care about something, it makes it easier to ignore your own discomfort.”

In the grand scheme of things, as members of a majority group, any discomfort we endure or criticism we receive in the course of learning will be trivial compared to being on the receiving end of oppression. And if that still isn’t enough, then at least consider this: that truly constructive criticism—the only kind worth listening to—is never personal.

“People might be worried about getting shamed for ignorance. I get shamed for being who I am,” Visakan points out.

“Maybe the question should be, how can people learn to get past their fear of being shamed? And I think the answer to that is to see the bigger picture and realise that it’s not about you, it’s not about any one of us.”