A couple of weeks ago, I wrote a piece for this site about the joys and complexities of attending an all-girls’ school. Of the 20 or so comments it attracted on Facebook, this particular exchange caught my eye:

Personally, I found this quite flattering. As someone who’s identified as a feminist since my early teens, I have no objections to being called ‘feministic’ (apart from the grammar). Nonetheless, while neither commenter explained what exactly they meant, I’m pretty sure they didn’t intend these as compliments.

Which got me wondering: are some Singaporeans still averse to feminism? And if so, why?

At my editor’s suggestion, and because my curiosity sometimes outstrips my sense of self-preservation, I decided to try and answer this by diving into more Internet comments.

This may be obvious to the point of being fatuous, but the Internet is not generally known as a nice place for women. Of course, this isn’t to say that men don’t get hated on, or to diminish what such men experience. Women, however, seem to draw a special kind of online animus: abusive comments that are all out of proportion to whatever prompted them, and unparalleled in their frequency and viciousness.

Amanda Hess, a journalist who’s written for the New York Times, wrote an essay detailing the barrage of online abuse she routinely receives, like “Im looking you up, and when I find you, im going to rape you and remove your head”. Lest you think this sort of thing is solely inflicted on Western journalists by worker armies in Russian troll factories, it is not.

It took me about 30 seconds to find this charming post on Sammyboy, referencing local journalist Kirsten Han’s receipt of an Honourable Mention from the World Justice Project for her reporting: “If she fucked harder she could have gotten an award instead of just a mention.”

This was just one. There were many, many more like it.

However, despite their reputation for toxicity, Internet comments are an excellent source of unfiltered opinions I wouldn’t otherwise hear in the echo chamber of my Facebook feed or social circles. Also, I was less interested in the sort of bile spewed by trolls and incels—the kind of vitriol so unabashedly hateful and logically tenuous you could identify it as garbage from ten miles away, half blind, with cataracts.

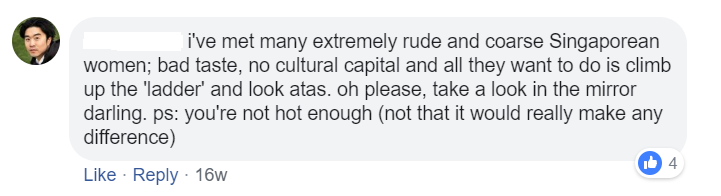

In other words, stuff like this comment left on a (female-authored) RICE post:

Pointing out the misogyny in something indisputably sexist is not especially illuminating, and at risk of having slightly too much faith in humanity, I didn’t think most people would condone such comments, or identify with the very vocal and extreme groups responsible for them.

Rather, I wanted to get a sense of why a sizeable proportion of people—regular people who wouldn’t make rape threats, who love their mothers and sisters and wives and girlfriends, who would even claim to support gender equality—nonetheless feel aggrieved by feminism’s continued existence, or believe it is unjustified, unnecessary, and unfair. In the hope of finding slightly more considered responses than the above, I spent a few hours trawling through r/Singapore. (If I’m being honest, self-preservation did trump curiosity to some extent; keen as I was to write this piece, I’m not paid enough to spend my weekend looking through HardwareZone and Sammyboy. There are some rabbit holes you just don’t go down.)

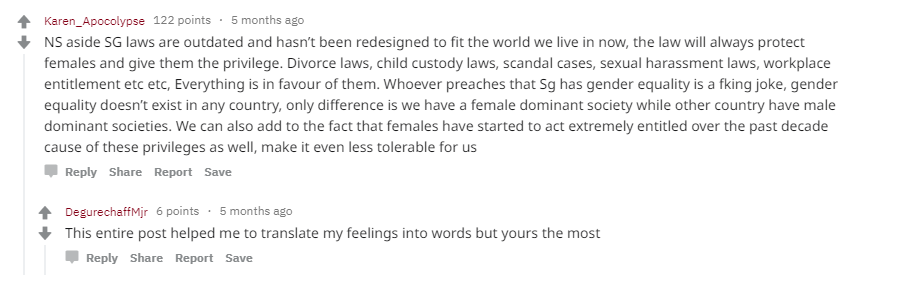

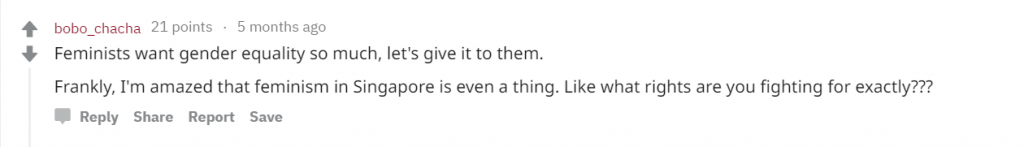

I started with the subreddits “Do men in Singapore feel like they’re underprivileged compared to women?” and “Redditporeans, do you think feminism is relevant in Singapore today?”, which elicited close to 400 responses between them.

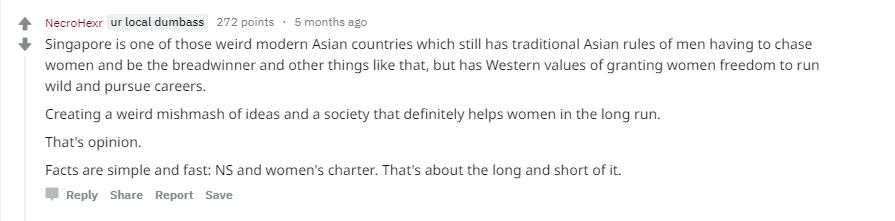

My hopes for thoughtful discussion deflated very quickly when I saw the top-voted post.

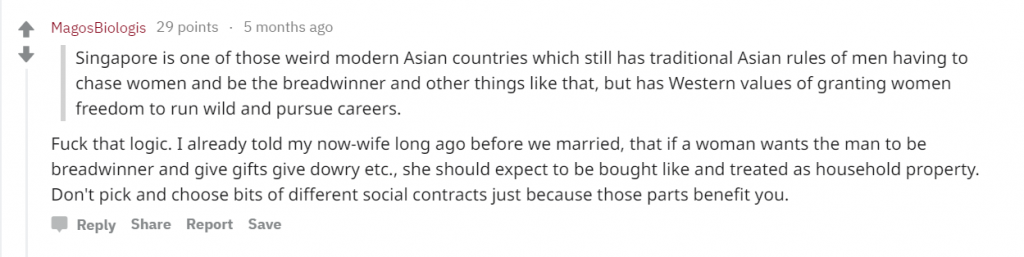

I had so many questions after reading this. What is ‘Western’ about women pursuing careers (or, for that matter, ‘Asian’ about men chasing women)? Why is it a ‘rule’ that men have to be the breadwinner and pursuer? Why is women being able to work a freedom to be ‘granted’, rather than a basic right? What does ‘running wild’ even mean? Stripping off my workwear and galloping through the fields of Punggol, with my hair swinging in the wind?

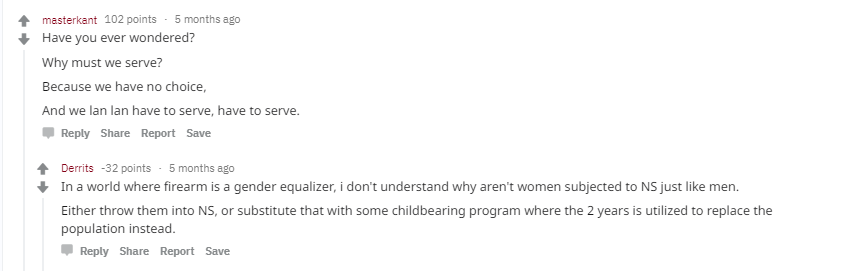

A couple were like something out of The Handmaid’s Tale:

To summarise, the arguments roughly fall along these lines:

1. Elements of Singapore’s legal system, namely the Women’s Charter and criminal laws concerning rape and sexual assault, treat men and women differently, in a way which favours women and disadvantages men.

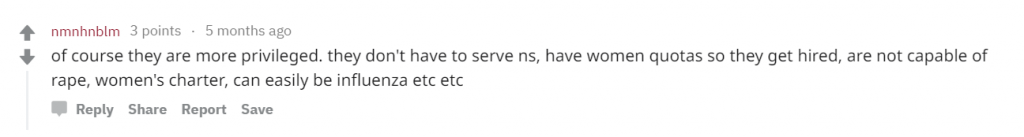

2. Men are discriminated against because they’re made to serve NS while women aren’t.

3. Empirically, women seem to be doing fine. Examples under this branch include, but are not limited to: I work in a female-dominated environment/educational achievement between genders is about the same/many Singaporean women expect the man to be the breadwinner or pick up the tab on dates/we have a female President. Moreover, women actually benefit from some gender stereotypes.

4. By a combination of some or all of these, Singaporean women aren’t actually oppressed, whether at the institutional or individual level. In fact, they have it much better than men, so why on earth are we talking about feminism and women’s rights?

Let’s explore these one at a time.

The legal system favours women

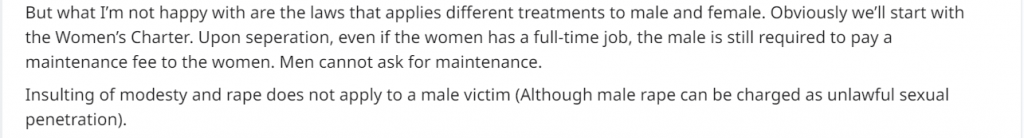

The allegations of bias here concern two areas: alimony provisions under the Women’s Charter, and various provisions of criminal law concerning rape and sexual assault.

For context, the Charter was enacted in 1961, when women’s legal, social, and economic circumstances were drastically different, though it’s been amended several times since. (It’s worth mentioning that the name is a bit of a misnomer; the Charter governs many areas of family law which concern men, women, and children alike). It currently doesn’t allow men to seek maintenance from their ex-wives (unless they are legally incapacitated, an amendment which was made in 2016), which many commenters cited as being unfair to men.

I wouldn’t disagree with this. Like all legislation, the Charter was a product of its time; one where polygamy still occurred, many women didn’t work or only worked in low-paying professions, and men were the sole breadwinners in most marriages. Given how things today look drastically different—many women do work full-time, and some wives’ earnings exceed their husbands’—this is an imbalance which should be addressed.

I do think the Charter’s maintenance provisions should be updated to let able-bodied men seek alimony, and reflect a more contemporary, gender-neutral view of marriage. (For the record, this is AWARE’s stance on the issue, too.)

This being said, and without getting too technical, wives are not automatically granted maintenance to begin with.

It’s still up to the judge to decide whether it should be awarded, and what a fair amount would be if so, looking at factors like the income, financial needs, and earning capacity of the parties. In addition, while dual-income families are much more common now, many more women are homemakers than men, or give up their careers to raise their families. While the law should be changed to make maintenance gender-neutral, its application still needs to recognise these practical differences.

Meanwhile, criticisms of the criminal law concern how, in law, only women are recognised as victims of rape. At present, rape is defined as the non-consensual penetration of a woman’s vagina by a man’s penis; if a man was subjected to non-consensual anal sex, or forced to perform oral sex on another man, that would instead be classed as sexual assault by penetration. Additionally, the current definition of sexual assault by penetration doesn’t cover cases of sexual assault perpetrated by a woman against a man.

Like the maintenance provisions, I’d agree that this is unfair. Every victim of sexual assault deserves the full protection of the law, regardless of their gender.

In this regard, however, things look set to change. The recent Criminal Law Reform Bill proposes expanding the definition of these sexual offences, recognising men as victims of rape and sexual assaults perpetrated by women, as well as the criminalisation of marital rape. All of these changes should have happened long, long ago. And as one redditor pointed out:

National Service (NS)

NS comes up a lot in regard to arguments of anti-male bias/female privilege in Singapore; in fact, it’s probably the most cited point there is. There is a whole subreddit called simply, ‘BUT NS!!!’.

People who bring up NS point not only to its mandatory nature, but to how NS imposes a lot of burdens beyond the initial two-year conscription: reservist, IPPT, needing exit permission, the opportunity cost of the two years (in terms of lost time and earnings), and the like.

I need to preface this section by saying that as a Singaporean woman, you learn very early on that nothing good comes of you saying anything about NS. It’s the touchiest of touchy subjects; the trump card which gets dealt in response to any suggestion of sexism. (In this regard, it’s telling that a separate subreddit exists asking for women’s views on the original—male-dominated—‘BUT NS!!!’ thread.) You will be howled down by protests of ‘but you don’t have to serve, you don’t get it, just stop’. (If you try to talk about NS on the Internet, the protests will be less civilly worded.)

So let me be absolutely clear: I won’t pretend to understand what NS is truly like. I didn’t serve. I don’t know. I doubt I would’ve enjoyed it. Giving up two years of one’s life to carry out tasks you have little to no say over in the name of our country’s defence is a big ask, as are the run-on costs and responsibilities detailed above. We don’t always pay enough attention to the welfare and safety of our NSmen, much as we should. And, for the record, I think NS should be an ‘all or none’ affair; I would support making NS compulsory for both genders, with options for military service or other forms of civilian service. (Again, it’s worth pointing out that this is AWARE’s official stance too, though they get the brunt of the hate around this issue.)

So yes: I think male-only conscription is unfair. But that isn’t all there is to it.

First of all, NS is predicated on an outdated, patriarchal system of gender stereotypes. Ones that cast men as protectors and defenders, and women as the ‘fairer sex’ in need of protection, or as having no role to play in national defence. And as much as women might benefit from this state of affairs (insofar as we enjoy the liberty of not needing to serve), these stereotypes do no one any good in the bigger scheme of things. They’re part of a larger landscape of assumptions which keep us from progressing in terms of how we think about gender. Second, anyone who points out that ‘NS is mandatory, childbirth isn’t’, as several commenters did, needs to go read The Handmaid’s Tale right now.

I can’t believe this needs saying, but having children is not a national obligation. It is not a duty that women owe men or the state. It is a choice. Women are not walking wombs. (To this end, to any ladies who do this—please, please don’t joke about childbirth as national service.)

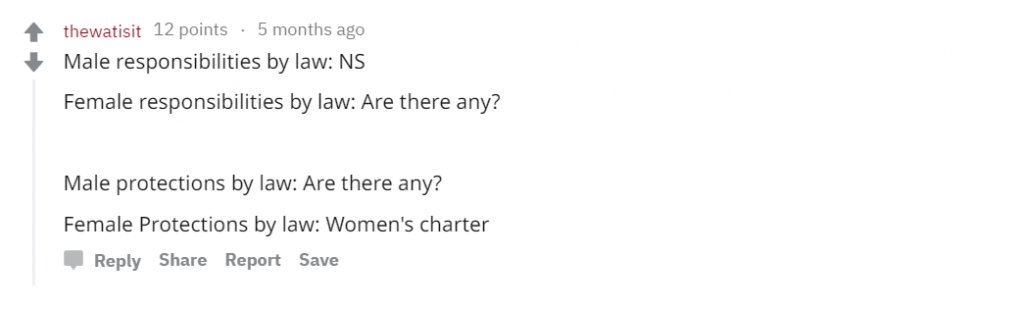

Third, NS is frequently used to shut down any claims of bias against women, or at the very least is presented as a sacrifice which trumps anything women encounter:

This needs to stop. If men are frustrated and resentful over having to serve NS, the issues lie with NS, not women. The former might be problematic and unfair, but you can criticise it without denying women’s claims about their lived experiences, or their right to talk about these experiences. And if you think that women have no right to speak out about sexism unless or until they serve NS, you think that a woman’s voice is conditional upon a man giving her permission to speak.

If that doesn’t justify why we need feminism, I don’t know what does.

To this end, whatever they might claim, some comments about making women serve NS have nothing to do with gender equality at all.

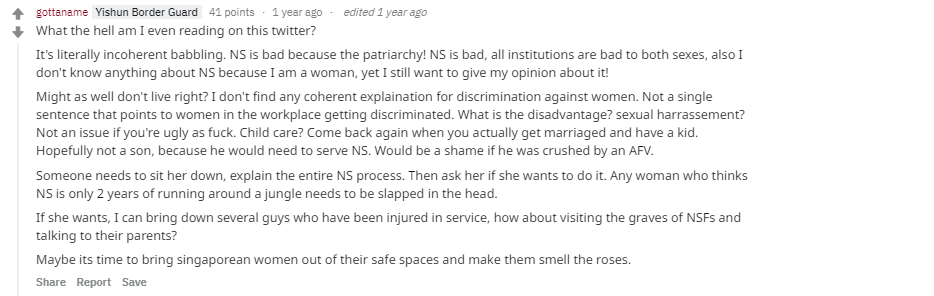

A response like this isn’t about the merits of making conscription gender-neutral. It’s not even about the writer projecting his bitterness and anger about NS onto women (though there’s a lot of that going on).

I don’t know anything about NS because I am a woman, yet I want to give my opinion about it. Sexual harassment isn’t an issue if you’re ugly as fuck. Someone needs to sit her down and explain it to her. Singaporean women need to brought out of their safe spaces.

It’s about the guy hating women. Plain and simple.

Anecdotal evidence and the ‘benefits’ of stereotypes

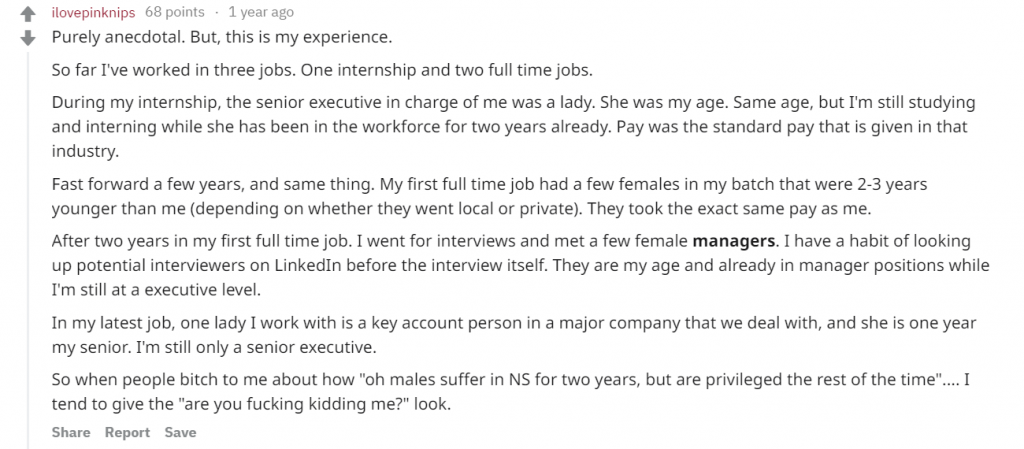

There are too many examples to list here, but anecdotes in this vein mostly cite examples of female achievement, as observed by the writer, as evidence that Singaporean women are doing just fine, if not better than men. For example: my boss is a woman, my colleagues are mostly women, more women go to university than men, women progress faster in their careers because NS, and so on and so forth.

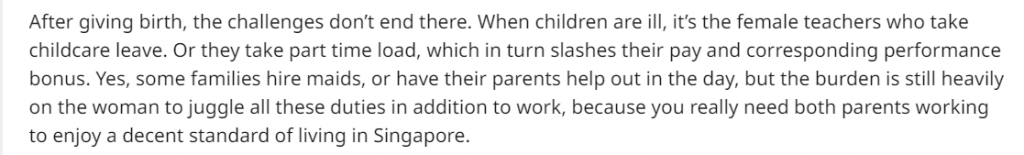

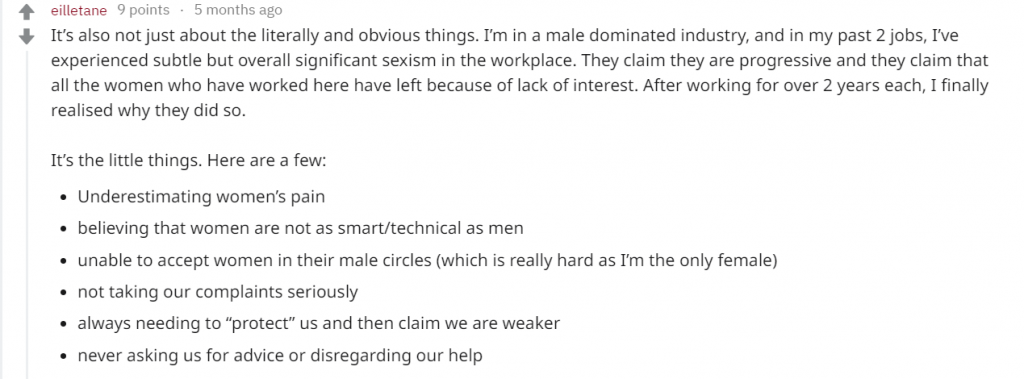

First, isolated observations—true as they might be—are rarely representative of the full picture. Yes, there are many female-dominated workplaces (though notably in ‘people’ industries like nursing or PR). Yes, we have women MPs and company directors and programmers. Yes, many women have good degrees and incredible CVs and well-paying jobs. But these examples exist alongside many less visible ways in which women experience sexism, like these commenters brought up.

As the second commenter pointed out, it’s not just that these challenges are less visible or obvious; it’s that when women do speak up, they often aren’t taken seriously.

A subset of the ‘but women do fine’ examples, and another oft-wielded complaint, is “But women benefit from gender stereotypes!”

People who argue this point to things like women who expect men to pick up the tab on dates or be the breadwinner, or, less commonly, how women can turn being objectified to their advantage (‘life’s easier for women when you wear a short skirt or makeup’).

A free dinner or drink here and there might be a benefit, yes. But this doesn’t mean women enjoy real power in these situations.

Casting men in the role of bank and provider puts women in the role of dependent, subject to men’s goodwill and generosity. (This is also how the Women’s Charter came to be.) Flirting your way to a free drink might seem harmless, but it only works if the guy thinks you’re attractive. In other words, it depends on what he thinks, which depends on any number of random things: how old/young/thin/fat/tall/short/un-made-up/too-made-up you are, and if you’re too much or not enough of any of these things … well, tough.

This isn’t power. It’s making the best of a belief system which rests on male benevolence, and leaves women to go along with the result. Neither men nor women should encourage this.

And finally, before anyone starts asking ‘why haven’t you talked about how gender stereotypes hurt men too’: I agree with you, as did a lot of commenters who raised this point.

They do.

I want to be clear, without descending into a long and fruitless game of Who-Has-It-Worse, that patriarchy hurts men too. I do not for a second believe that men don’t suffer because of it—from boys being raised to think of emotions as unmanly, to stifle their feelings or anxieties for fear of judgment, to the pressures of being lumped with the protector-and-provider role (yes, this includes NS), to the much shorter paternity leave that fathers enjoy. Loneliness and suicide rates are higher for men than they are for women.

These are all real and serious effects—effects in and of their own right, not side effects—of patriarchy which need to be addressed.

I would add, though, that gender stereotypes affecting men have parallel consequences for women. Boys who aren’t raised to live healthy emotional lives often become men who take the emotions they can’t deal with out on their partners, with their fists or words or wallets. Men who resent being labelled breadwinners and defenders are often men who think women need protecting because they don’t know anything about the world. Fathers don’t get enough paternity leave, but for a good many people, mothers are still the default caregiver anyway.

Nobody wins under this.

Women in Singapore have it good. Feminism is irrelevant here

So where does this leave us?

It might have started out that way, but feminism isn’t just about addressing inequalities at the legal or institutional level. It also looks at the social, cultural, and economic spaces in which we operate.

Life is governed by so much more than the contents of our statute books. Alongside these is a spiderweb of a hundred little gendered assumptions woven through our thoughts and choices and actions and policies, sometimes hard to pin down or articulate, usually hard to talk about.

Having legal rights that give protection from gender discrimination, or redress for the same, is one way to talk about empowerment, and an important one at that. But having the freedom to go through life as a full human being, without expectations or judgment or setbacks because of your gender, is another.

And here, I think, is where feminism in Singapore today remains especially important and necessary, and where our conversations need to venture. Because while women here might not face oppression at the legal or institutional level, or at least not to the degree that women in other countries do, we still have a long way to go in other respects.

If people still find a woman abrasive or intimidating for voicing her opinion, then we need feminism. If people still think that women who voice their opinions, even—or especially—controversial ones, don’t know what they’re on about and need to be put in their place, then we need feminism. If women feel the need to preface requests with ‘I was just wondering…’ or ‘Sorry to bother you…’ so they don’t come across as demanding or troublesome, then we need feminism.

If people have no issues with women working, but we’re uncomfortable if they earn more than their husbands, then we need feminism. If a woman’s social capital diminishes with her age, while men are seen as wiser and more experienced the older they get, then we need feminism. If it still disproportionately falls to women to carry out emotional labour—to send the ‘thank you’ cards and remember birthdays and organise family gatherings and carry out the never-ending work of making people feel wanted and valued—and people assume these things happen ‘because women are naturally more caring’, then we need feminism. If people assume that women are innately maternal/more emotional/more complicated than men, or that men are inherently more decisive/logical/straightforward, then we need feminism.

If people still think of sex as part of a husband’s needs which his wife should try to fulfil, then we need feminism. If women are still made to feel embarrassed about menstruating or masturbating or enjoying sex, then we need feminism. If women are reluctant to talk about being sexually assaulted because someone will say they asked for it, then we need feminism. If women worry about starting families because they might be denied promotions or be seen as ‘distracted’ or ‘uncommitted’ to their jobs, then we need feminism. If many capable women in middle management leave to raise their families because they’re still the primary caregivers and workplace policies don’t allow for flexi-time, then we need feminism.

If queer and trans women are still thought of as ‘not woman enough’, then we need feminism. If the bulk of caregiving and child-rearing responsibilities still fall to women, then we need feminism. If we underpay our foreign domestic workers and deny them basic employment rights because, amongst other things, we undervalue the ‘women’s work’ that they do, then we need feminism.

We’ve come a long way, we really have. But we can still do so much better.

And now, having finished this monster of an essay, I’m off to run wild like the entitled, snowflake-y, SJW feminist I am.

Do men need feminism as much as women do? Tell us what you think at community@ricemedia.co.