Loosely defined as a “tendency to seek distraction and relief from unpleasant realities, especially by seeking entertainment or engaging in fantasy”, escapism isn’t something new. It is a very human thing, especially in the wake of something particularly unpleasant, like a global pandemic. But now that fantasy is just a click away, escapism is that much easier to indulge in.

Escapism gets a bad reputation. It’s often dismissed as avoidance or flat-out refusal to confront reality. It comes in many forms: binge-drinking, abusing drugs, playing video games for hours on end, or even eating your children’s candy. Any activity that lends itself to distraction, it seems, can count as escapism, but it is usually the more destructive and less conventionally productive ones that come to mind.

Experts tell us that escapism prevents us from confronting reality. It’s associated with depression, alienation, and addiction. Spending hours glued to Mobile Legends, clearly, is a sign that we are not willing to be responsible for our own lives.

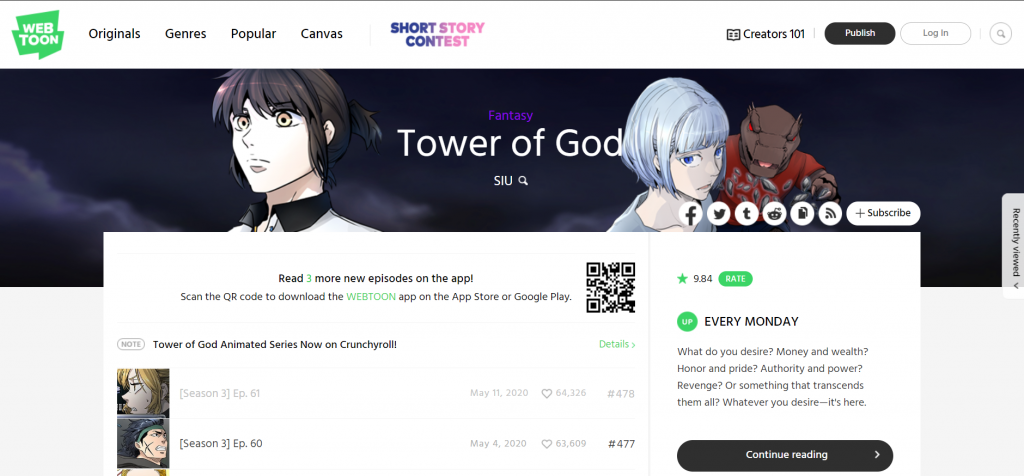

When was the last time you took the entire weekend off and immersed yourself in the newest book? Can you remember the joy of discovering a new series and then spending the next six hours on fanmade Wiki pages?

If you’re spending seven days a week on your bed, to the point where you get dizzy when you get up, then you might be overdoing it. But that isn’t what escapism looks like for most people.

Activities like binge-watching are labelled as temporary, unhealthy coping mechanisms, but they grant us pockets of relief when reality gets too much. Speedrunning through Tiger King in half a day was an invigorating experience as much as it was a proud accomplishment. I sat enraptured by the sheer insanity of it all, coming out of it as excited as a 12-year-old who just finished her PSLE. In a time when the news can get too much, too fast, diving deep into Joe Exotic’s world was a breath of fresh air.

Escapism gives that illusion of normality during times of abnormality. Under usual circumstances, escapism could look like heading to the club so you don’t have to think about the assignment that is due tomorrow. Escapism is not confined to situations of isolation. But, now, we have no choice: we have to engage in escapism while being isolated, and that makes it terribly easy to spiral.

But, as I worry about my increasing screen time, I find that these long stretches of immersing myself in another world are what allow for breathing room. Asking around, I realise that others feel the same way.

Now that she has more time on her hands, Ianna is starting to watch more streamers on YouTube.

“It’s fun to see them interacting with the audience,” she tells me, “and I engage in the game without being worried about my score.”

Her decision to go down a YouTube rabbit hole on any night is a conscious one. The fact that she is not obligated to watch any of them—she has full power over whether or not she wants to continue binge-watching—allows her to enjoy everything at her own pace.

Atharv has also noticed that his parents are watching television dramas more often. Television channels from India are rebroadcasting old shows, and there are series that get more than 100 million viewers—that’s more than the Game of Thrones finale. They are working fewer hours, now, and diving deep into these shows is a happy pastime that they have rediscovered.

The pandemic is helping us realise the value in what is framed in the narrative as “doing nothing”. We now have the space and time to indulge in the things we once enjoyed but might have shelved aside in favour of what we thought was more important.

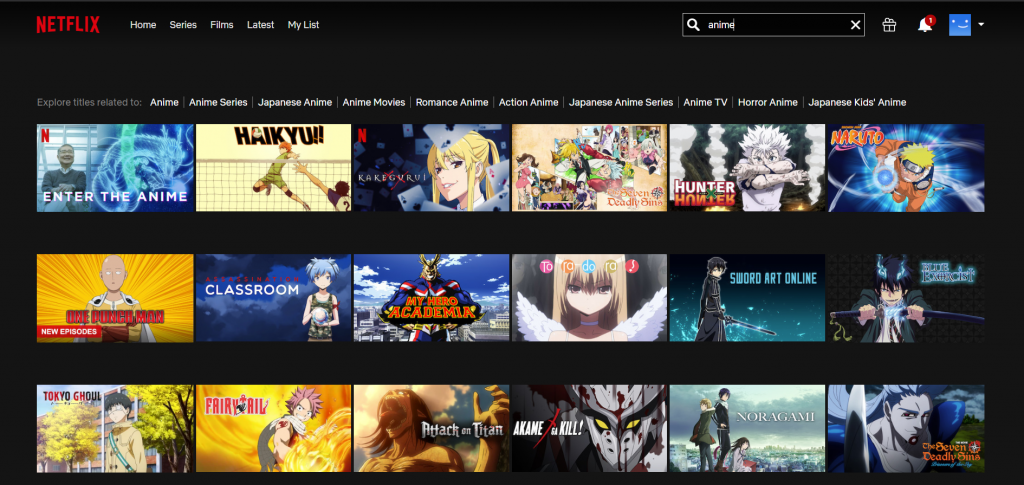

A self-proclaimed workaholic, Audrey now finds herself watching Netflix more and rediscovering the joy of baking, things she couldn’t do before the circuit breaker. “Honestly, I hope that even when this pandemic is over, we don’t completely forget about these activities that gave us so much joy during CB and still set aside time for them occasionally.”

We don’t know what the new normal will be like. But we do know that escapism, as much as it gets criticised every so often, has value. And we could do with a little more of it.

Jeremy Sherman argues that we need escapism: “We face way too much reality, more than a body can stand.”

We can afford ourselves that sliver of breathing space. We need that slice of fantasy, every once in a while, and the childlike joy that comes with it.