Top image credit: original image by Boudewijn Huysmans on Unsplash.

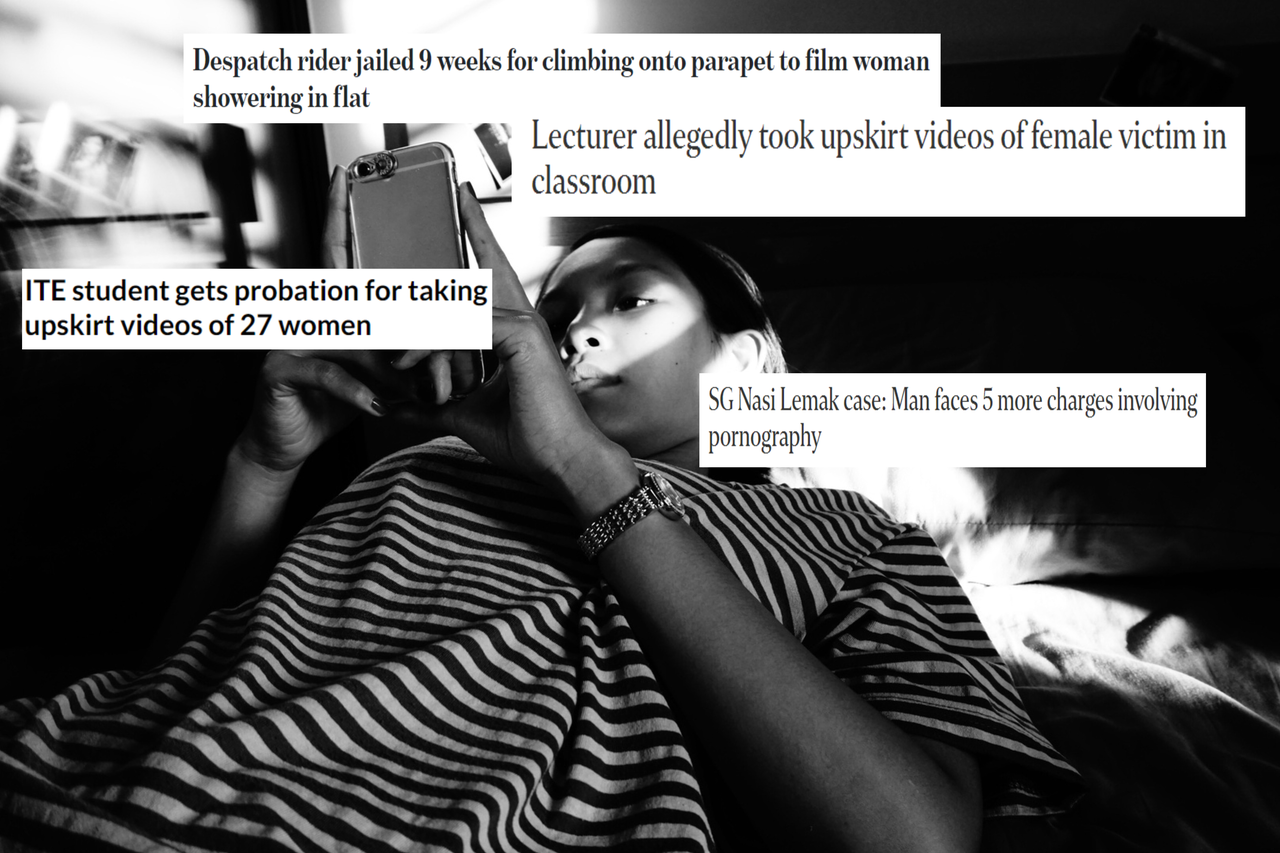

For most of 2019, between voyeurism incidents, upskirting videos, molestation/outrage of modesty cases, and Telegram chat groups like SG Nasi Lemak, it felt like a week didn’t go by without a new report (or four) of yet another case of sexual violence. In November alone, over 20 cases of sexual assault/or misconduct were reported in the Straits Times, TODAY, and CNA.

In one sense, this is welcome. The gravity of sexual assault cannot be understated, and it needs to be kept at the forefront of public consciousness if things are ever going to change. (To be sure, the rise in reportage might simply be that: a rise in the number of cases making the news, rather than in the absolute number of new cases. This would also reflect a judgment call on the part of the media, insofar as editors try to move in step with readers’ appetites.)

However, as anyone who has been following the news will have realised, keeping abreast of all this—and figuring out where to go from here—is exceptionally difficult.

First of all, the ‘conversation’ to date has largely stalled at discussing the adequacy of punishment. Public sentiment has shifted; institutions and law enforcement can no longer afford to be seen as being soft on sexual assault. Despite this, we haven’t done much more than bay for perpetrators’ blood.

We have largely not progressed to true soul-searching, accountability, and examining the people, systems, and infrastructure that facilitate sexual violence. The anger which Monica’s case stirred up brought about some significant changes, mostly with regard to universities’ sexual assault policies, but has not yet spawned a reckoning in the way #metoo galvanised the US/UK.

Additionally, despite the barrage of reports, we still see incidents of sexual violence as isolated cases, rather than a broader cultural epidemic in which everything from SG Nasi Lemak to voyeurism is connected. This makes it all the more urgent that we figure out a way forward before the conversation loses steam, incidents fade into white noise, and the year passes without a sense of the lessons learnt.

As such, here’s a non-exhaustive list of considerations we’re keeping in mind for 2020.

2019 has seen some important, much-needed changes. Amongst other things, specific legal provisions for adressing voyeurism and technology-facilitated sexual violence (TFSV), enhanced university disciplinary policies, and improved support for victims/survivors are all constructive, and welcome, developments.

However, these are only one aspect of combating sexual violence. We need solutions that go beyond dealing with sexual assault cases as they arise, and aim to stop them happening in the first place. Moreover, responsive measures can be limited by the phenomena they’re developed to address; as problems evolve to find ways around the system, we risk getting stuck in an endless game of legal and regulatory catch-up.

As such, we need to look upstream and ask ourselves: what are the attitudes and beliefs which contribute to sexual assault, and how can we drive a cultural shift away from these?

As Rebecca Solnit wrote in the Guardian over two years ago, “[T]he change that really matters will consist of eliminating the desire to do these things, not merely the fear of getting caught.”

In the US and UK, #metoo unleashed a tidal wave of sexual misconduct allegations that rocked whole industries, from media and entertainment to F&B and politics. Across 2017 and 2018, women flooded social media with accounts of how they were subjected to unwelcome advances, or expected to provide ‘services’ in return for career progression, revealing workplace sexual harassment as a gnawing, rotten epidemic.

A similar shake-up has not taken place in Singapore.

At this stage, it’s difficult to determine the scale of the problem here. A Straits Times article from November 2017, citing HR experts and lawyers, suggested that it is “not uncommon here but they do not know the extent of its prevalence”. The closest I could find was an AWARE survey from 2008, in which almost 55% of 500 respondents reported experiencing sexual harassment at work (they are currently recruiting participants for another study).

Anecdotally, there’s reason to believe the situation on the ground is grave. Any woman who works in F&B, for example, will have stories that range from lewd jokes and unwelcome stares to coworkers openly pressuring them for sex (especially if they are service staff, or in junior roles in the kitchen). However, we won’t know how extensive the problem is without greater scrutiny—as well as mechanisms to help victims feel safe enough to come forward.

#metoo didn’t just take powerful abusers like Harvey Weinstein, Louis CK, and Mario Batali to task. The movement also called out the people and systems which assisted them, whether by helping to cover up allegations, disregarding victims’ complaints, or other innumerable forms of silent complicity in sexual violence.

In Singapore, one of the clearest examples of the last category—which we haven’t yet figured out how to deal with—is the passive consumption of intimate material which has been non-consensually shared online. In other words, what do we do about the bulk of the 40,000 members of SG Nasi Lemak and its ilk: men who might not have uploaded images themselves, but have no qualms about joining the groups and getting off to their contents?

Legally, these members are as culpable as people who originally shared the material. I spoke with Priscilla Chia, a lawyer, who clarified that the amendments introduced in the Criminal Law Reform Act 2019 (coming into force next year) criminalise both possession and distribution of such material.

At present, it remains to be seen how these amendments will translate in practice. But more importantly, the ‘wrongness’ of passive consumption needs to play out in the court of public opinion, not just of law. Insofar as this continues to be seen as grey area rather than a black-and-white issue, there will still be work to be done.

Victims of TFSV should have clear, accessible guidance regarding the options available to them. It’s not always apparent whether seeking redress through the law, or through the tech companies involved, provides the most efficient, effective, and victim-sensitive avenue for recourse. (There are, of course, gaps in each. For example, the provisions on TFSV in the Criminal Law Reform Act are extensive, but do not apply outside Singapore. Meanwhile, tech companies’ takedown policies, despite relying on both AI and human enforcement, are not watertight.)

To this end, technology can be used to resist sexual violence as much as perpetuate it, as Monica’s case demonstrated. However, victims of TFSV (or any form of sexual violence) should also be made aware of the risks of looking for redress online. Much as social media can seem like an outlet for seeking justice, a carelessly worded IG story could open the subject to doxxing—and the victim to being counter-sued for defamation.

It’s clear that the police, social services like victims’ support and advocacy groups, and universities all have major roles to play in combating sexual violence. However, responsibility doesn’t end with them.

Take education, for one: how we talk about sex, desire, intimacy, and boundaries needs to change. Sex (and consent) education should start earlier, and proceed in a far more nuanced and healthier fashion, than it currently does.

When it comes to TSFV, tech companies need to do their part by swiftly removing material, maintaining transparent takedown policies and channels of communication, and emphasising a zero-tolerance culture towards TSFV. Media should go beyond simplistic narratives in reporting on sexual violence, and pay greater attention to the systems, structures, and inequalities which enable it. Ultimately, all of us, as members of civil society, have a role to play in changing the culture around sexual assault.

Amidst all the sound and fury, the needs and dignity of one very important group must be kept in mind: victims.

We need to accord space and respect for victims’ opinions, especially regarding how to tackle sexual violence sensitively and effectively, and the kind of support most needed by victims/survivors.

When an injustice occurs, it’s all too easy to get caught up in our own indignance and self-righteousness, without asking victims what they think. For example, we should not pressure victims to pursue their cases or share their stories ‘for the greater good’; how to proceed is their choice, and never an obligation.

Similarly, after Monica went public with her case, she ended up expending considerable time and energy managing the Internet’s feelings, rather than her own—both requesting that people not doxx her harasser, and keeping a handle on the backlash she received. This should never have happened. Victims’ requests for privacy, whether for themselves, their families, or even their assailants, should be respected at all times.

Punitive measures are important. They act as deterrents, send a message of zero-tolerance, and—most crucially—hold perpetrators accountable for their actions.

However, we ought to bear in mind that punishment, or at least punishment with no further follow-up, may not always be the best (or only) course of action.

What this is is never clear, and what justice looks like in the context of sexual violence is a sensitive and difficult question. This said, it’s worth wondering what sort of scope there may be for rehabilitative justice. For example, what about cases where the perpetrator is a minor? Or where they are known to the victim (as is the case in many instances of sexual violence), and a more complicated matrix of relationships, wishes, and priorities might be at play?

Victims of sexual violence and misconduct, be it physical assaults, TFSV, or workplace sexual harassment, are overwhelmingly women. However, men can be victims of sexual violence too—and not enough is known about this, or the scale on which it occurs.

Data on this is almost impossible to come by. Although the Criminal Law Reform Act included an expanded definition of rape and sexual assault, which recognises that men can be victims of such offences, barriers to reportage and investigation are numerous. Internalised shame, myopic definitions of masculinity, and the fear of stigma or insufficient support all hinder victims from coming forward.

Needless to say, all victims of sexual violence should be supported in their journey of recovery. We need to acknowledge that sexual assault can occur regardless of gender, while also taking into account how gender, and its specific power dynamics, plays a role in shaping the landscape of sexual violence.

On that note, however, men have been notably absent from the debate around sexual violence.

This cannot continue in 2020, not just because perpetrators of sexual violence are largely male, but because men need to do better at speaking up and holding each other to account.

By now, it should go without saying that patriarchy hurts men too. Unrealistic expectations of masculinity trap men in the gap between who they think they are and the men they feel they should be, and the consequences of this are devastating for both genders. However, we can accept this while also encouraging men to recognise where and how they devalue women’s voices, experiences, and concerns.

Significantly, this goes beyond getting men to call out other men who actively commit sexual harassment or assault. More men need to recognise that their own assumptions and passivity contribute to a climate of tolerance for sexual violence, even if they haven’t committed an offence themselves.

2019 has been a watershed year for our evolving response to sexual violence. The climate has decisively, and necessarily, shifted in favour of zero-tolerance, as well as enhanced support for victims’ welfare.

A whole range of parties, from lawmakers and law enforcement to activists and support groups, all deserve credit for this—not least, the many victims/survivors who have bravely come forward to share their stories.

However, public sympathy (or outrage) is still more easily stirred by clear-cut, open-and-shut incidents with a clearly identifiable perpetrator and/or victim. It’s easy to point fingers and demand action when a case fits recognisable models of wrongdoing: a voyeur snapping upskirt photos of unsuspecting schoolgirls, or a lecherous boss propositioning a young, female colleague.

But there is no such thing as a ‘perfect’ victim—or rather, there are plenty of ‘imperfect’ victims, with nuanced cases that don’t always conform to our expectations of what perpetrators and victims should look like. Power, privilege, and bias all affect our inclination to believe and support victims, and consequently, their willingness to come forward.

Going forward, the real test will come in terms of how we respond to these ‘grey’ cases. This isn’t to say that sexual violence is ever the victim’s fault—it isn’t—but we have not yet reached a point where we treat all cases with equal seriousness, regardless of victims’ circumstances.

Sex workers, for example, are especially vulnerable to sexual assault, but rarely command the same degree of public sympathy. Similarly, as Monica and other advocates have pointed out, many still think of TSFV or voyeurism as ‘less serious’ than physical sexual assault.

As such, we need to confront the elephant in the room: we cannot discuss sexual violence without also examining how gender comes into this.

The 20+ incidents in November were not isolated cases. They are manifestations of a broader culture which still links women’s personhood to their standing as wives, girlfriends, and mothers in a socially assigned script, makes their worth dependent on this, and allocates men the role of judge.

It’s often suggested that a failure of empathy (of men for women, or perpetrators for victims) is responsible for this phenomenon. There is truth in this, and recognising individuals’ full, lived humanity is a crucial step. But it doesn’t go far enough.

Empathy is inherently neutral, and means very little without accompanying action. Moreover, it has its limitations. Members of SG Nasi Lemak, for instance, would probably balk if they came across photos of their girlfriends or female friends, but have no qualms about the group’s content otherwise.

Similarly, the jealous boyfriends who perpetrate revenge porn do not do so because they can’t empathise with their exes. They do it to humiliate, intimidate, and control women who have failed to play their parts, and denied them things to which they feel entitled: love, attention, and sex.

The only way forward is to confront our expectations surrounding gender: what we expect from, and of, men and women, under a toxic system which marginalises one, privileges the other, and ultimately hurts them both. Until we commit to the long, hard work of addressing power imbalances between men and women, and recognising how these connect all forms of sexual violence, 2020 is going to feel like one long, painful exercise in deja vu.

AWARE contributed media tracking figures for November 2019.

Did we miss something out? Let us know at community@ricemedia.co.