My first brush with anti-semitism strangely involved a beanie hat and David Blaine.

This was during the early 2000s, a simpler time when emotional breakthroughs were achieved via Linkin Park songs. In an era when Fred Durst was an actual icon and people were unironically listening to Sisqo’s Thong Song, all I wanted was a beanie from 77th Street. As part of my teenage quest for status symbols, I wanted to be known as The Guy Who Always Wore a Beanie.

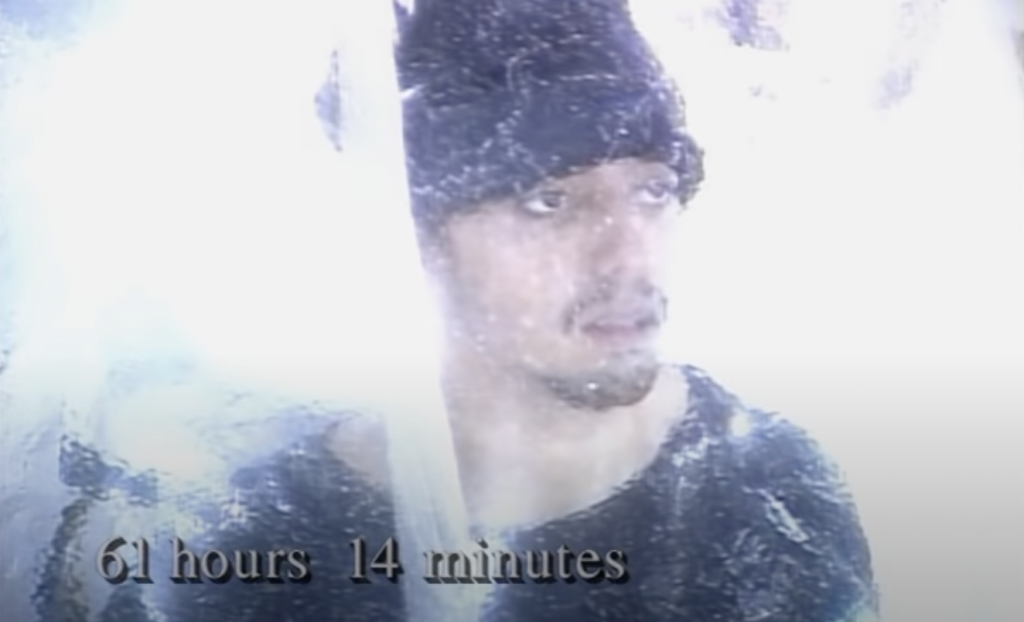

And so I wore a damn knitted cap for months, convinced I was a cool kid despite the streams of sweat cascading down my Gatsby-gelled noggin every time I stepped outside. My mother was impressed by my juvenile perseverance for this look—up till the night when we were all watching David Blaine encase himself in a block of ice on Channel 5.

As the family watched the brooding, overdramatic magician enduring the cold stunt for hours with a beanie on, my mother suddenly chimed in with genuine concern: “Are you trying to look like him? You know he’s a Jew right?”

Even today, way past the beanie-donning days and a cringe-worthy foray into fedoras, I don’t know if I can blame her, my father, or any other Malay-Muslims in their generation for their distrust of Jewish people. Unfortunate as it is, anti-semitism is common within Malay-Muslim households in Singapore—many other impressionable kids like me have been taught and told that “Jews were bad people”.

Unlike the Western notion that connects Jews with money, our families associated them with wanton cruelty. Jahat macam orang Yahudi (“as wicked as a Jew”) has been a common refrain. Perangai Yahudi (“Jewish behaviour”) is used as an insult, but the enduringly popular perangai babi (“pig-like behaviour”) just rolls off the tongue better.

This ingrained anti-semitism stems primarily from the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian hostilities, a century-long struggle taking place nearly 8,000 km away from Singapore. Like many other Muslims here or around the world, we’ve been horrified and disgusted to the point of jadedness at the horrors of eviction, homelessness, death, and destruction erupting in the region.

These days, the constant barrage of information online is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, we’re getting live, intimate updates of the dire situation in Gaza; an on-the-ground showcase of brutal bombing campaigns. On the other, it intensifies the anti-semitism (or anti-Palestinian sentiments, if you’re on the other side) with dozens of one-sided videos, clips, and posts. Facebook algorithms and WhatsApp chat groups aren’t exactly known for providing nuance.

The re-ignition of intense discord in recent weeks—erupting in the worst violence between Israelis and Palestinians in years—can’t be avoided on social media, or at least, across my personal feed. Posts made by social justice circles went viral before getting unceremoniously taken down. The Islamic Religious Council of Singapore (MUIS) condemned Israel’s violence against worshippers holding Ramadan prayers at Jerusalem’s Al-Aqsa mosque (but not everyone agreed with them reaffirming Singapore’s two-state solution stance).

Others reckoned with the guilt of visiting family members in their fresh Hari Raya outfits, stuffing themselves with ketupat and rendang while Palestinians marked Eid with bombs raining down on their homes.

As I watched my mother doing her market shopping with a #FreePalestine tote bag and heard my dad reminisce about their trip to Al-Aqsa—the very same holy site where Israeli forces fired tear gas and stun grenades last week—it begged the question: Why is solidarity with Palestine such an entrenched notion within Singapore’s Malay-Muslim community, bordering on the edges of anti-semitism?

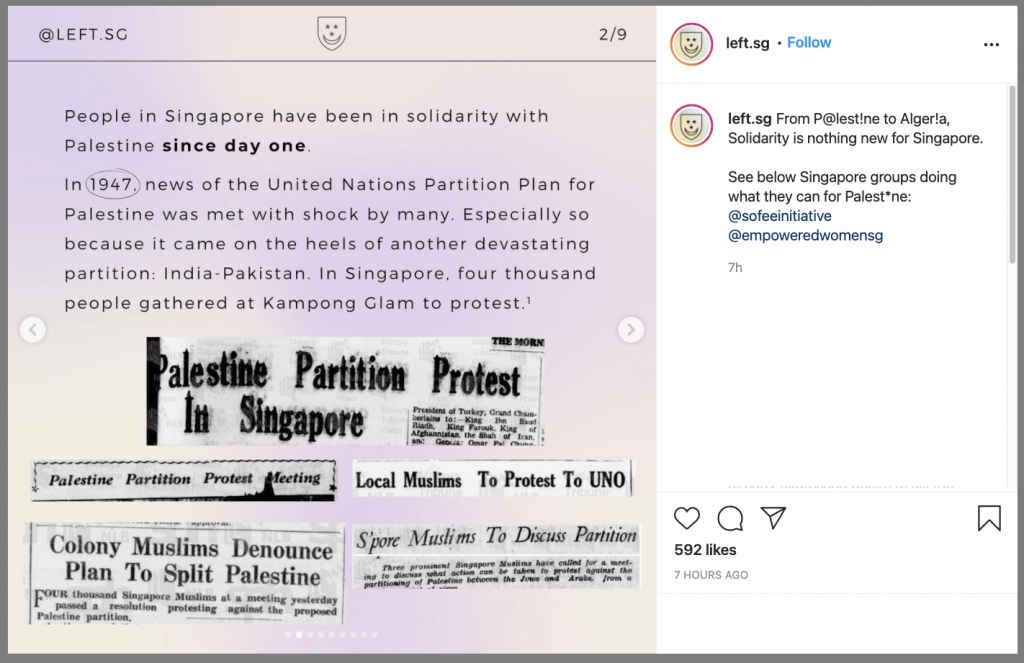

The obvious answer is, of course, affinity with fellow Muslims—especially innocent Muslim civilians who have lost homes, family members, and lives in a bleak humanitarian crisis with no end in sight. If you ask the people behind @left.sg, Muslims in Singapore have been in solidarity with Palestine “since day one”, citing reports from 1947 of a massive protest in Kampong Glam denouncing the United Nations’ partitioning of Palestine into Jewish and Arab States.

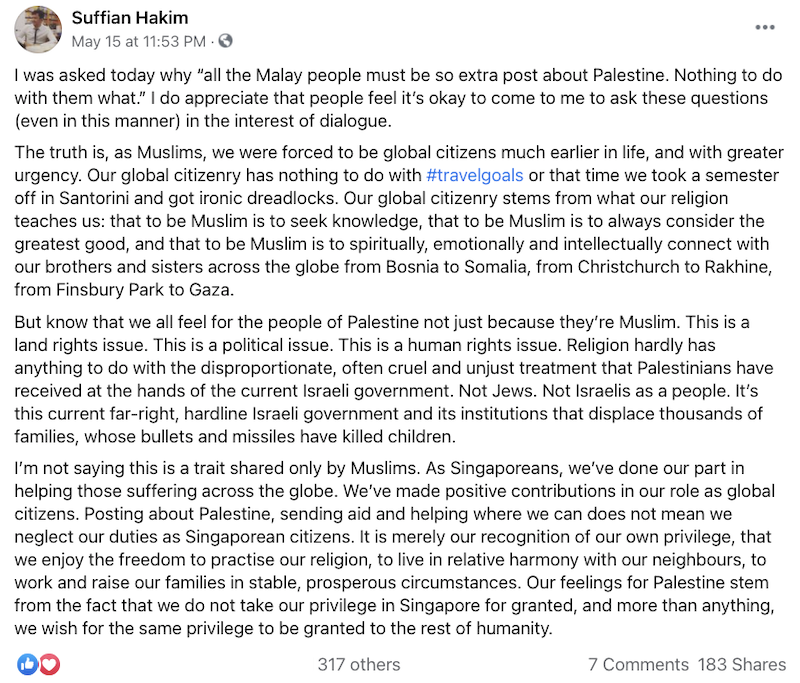

Suffian Hakim, author of ethnically-tinged comedic novels like Harris bin Potter and the Stoned Philosopher, posted a more serious, nuanced note on Facebook when he was asked why the Malay community has been “so extra” of late about the plight of Palestinians. Aside from religious solidarity with Muslims worldwide, he puts forth that it is our recognition of privilege in Singapore (peace, prosperity, religious stability) that drives the community to be so public about the struggles on the other side of the world.

More importantly, Suffian attributes the unjustified violence against Palestinians to the Israeli government instead of blaming the Jewish people.

“Not Jews. Not Israelis as a people. It’s this current far-right, hardline Israeli government and its institutions that displace thousands of families, whose bullets and missiles have killed children.”

Like myself, he too, grew up with some anti-semitism at home. Like myself, he too eventually realised the difference between the Israeli people and the Israeli government. I asked Suffian why the older folks in our community still hold deep grudges against Jews, which they’ve passed down to their kids.

“I honestly think because most of them reached political maturity around the time of the first Intifada. Our parents and older relatives were in their 20s and 30s when the first Intifada happened and they split their media consumption mainly between local TV and Malaysian channels like RTM and TV3, right?”

This much was true. My childhood did involve jiggling around the old TV antenna as my dad messed around with the tuner to receive Malaysian broadcasts. Malaysian news channels, as Suffian points out, showed a lot of footage of suffering Palestinians, no doubt with an Islamic slant to the ongoings of the crisis.

This, on top of the Singaporean Malay community’s cultural similarities and familial connections with Malaysian Malays—a country that still has yet to recognise Israel’s sovereignty.

Closer to home, it didn’t help that the local Malay-Muslim community were not taken into account in the early days of National Service, modelled after the mandatory conscription of the Israeli Defense Forces, and even with Israeli military advisers brought in to help set the programme up. What’s not widely known is that Malay youths were excluded from conscription from 1967 to as late as 1984, which in turn, held dire consequences for the community’s socio-economic standing. When they were eventually let in, they were mostly deployed to serve in the police force or the fire brigade.

Those who managed to make it into the military were given menial jobs. Alon Peled, an associate professor and political scientist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, noted in his paper (A Question of Loyalty: Ethnic Minorities, Military Service and Resistance) that discrimination against Malays in the military was simultaneously surreptitious and obvious:

“By the second half of the 1970s, Malay exasperation with military recruitment and discrimination policies reached an all-time high. Even without official data, Malay parents knew that their children alone were not called upon to serve. Malay officers and (non-commissioned officers) who had been transferred from field command positions to the logistics corps were also frustrated. Nearly every officer knew that military units had informal quotas on Malays.”

That distrust from the early days extended into an overarching wariness of Jewish people, compounded by how little they’ve been exposed to Jewish culture or even the small Jewish community in Singapore.

While I’m certainly not equipped to outline the contours of the Israeli-Palestine crisis, I’m sure that we can differentiate an entire Jewish race from the actions of the Israeli government and the far-right fringes of Israeli settlers forcing Palestinians out of their homes. Just as the other side can differentiate innocent Palestinians from the actions of Hamas.

You can protest unjustified violence without resorting to abject anti-semitism. Direct your criticism at the crimes of apartheid and persecution perpetrated by Israeli authorities. Blame the British imperial colonisers. Point fingers at extremists on both sides who intentionally fan the flames of hate.

It would also be right for the Singaporean Malay-Muslim community to realise that not all Jewish people are against them, many of whom have even publicly spoken out against violence against Palestinians by establishing advocacy groups or taken other more extreme measures.

It is, however, not a controversial stance to sympathise with those who’ve suffered heavier losses.

Taking a step back, there are other more immediate priorities to worry about, like the recent spike in COVID-19 cases here. But when one grapples with the idea of not being able to celebrate Hari Raya Aidilfitri properly this year against the fear of airstrikes raining on clinics, hospitals, homes, and children, one can’t help but reflect on the cyclical nature of perpetual strife and ingrained animosity. And hope for better days.

Have something to say about this story? Write to us at community@ricemedia.co.