“She chio or not?”

At a recent dinner with old friends from JC, conversation inevitably meandered: we traded stories about our lives, the crazy events of 2020, and when topics for discussion were exhausted, turned to idle gossip.

We talked about whether there was veiled misogyny at our alma mater (had this been a dinner with a bunch of females, this would not have been a question—there clearly was). We talked about the ‘Elite Four’, a ranking of the top four most desirable girls that time and time again made its appearance in each cohort, and even the supposed practice of ranking the ‘Bottom Four’, which needs no further explanation (though thankfully that was not a thing in my year, at least to my knowledge).

But this casual objectification of women over coffee pork ribs and heaping mounds of rice ate away at my sense of comfort. As I had done many times before, I couldn’t help but point it out.

I asked if they knew about how common eating disorders were amongst the girls in our level. They didn’t. I asked if they’d considered what it would feel like to be the only male in a group of female friends, listening to a casual conversation about some other male’s body part. I asked them if they thought it was acceptable to talk about banging some other girl, someone who was a friend to all of us.

My friends listened, as good friends do, with growing sobriety. I agreed that females doing the same would be problematic, but that did not discount the fact that males doing it was particularly harmful, because it contributes to a culture of misogyny, scaffolded by a power imbalance between the two sexes.

In 2019 and 2020, Singapore was rocked by a steady stream of sexual violence misconduct cases perpetrated by university students.

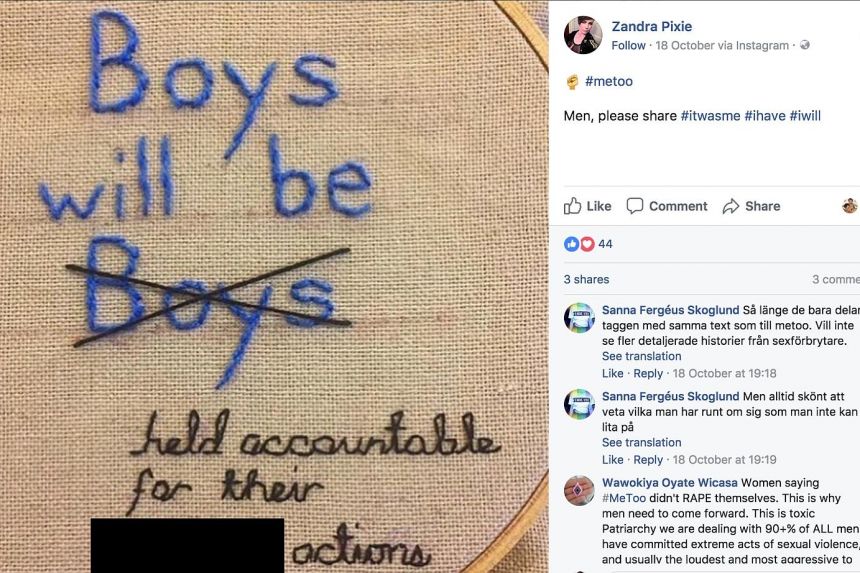

There is no lack of criticism for our generation’s quickness to blame the patriarchy for everything, yet no one can deny the power in attributing individual, seemingly disparate experiences of unfair treatment to an invisible, but very much tangible, power structure. This is what gave the #MeToo movement in 2017 its momentum. But I am realising that alongside more women speaking up about the injustices they face, the patriarchy and its effects need to be made intelligible to our male counterparts.

That evening, it became clear to me that my male friends had rarely been confronted by the lived reality of being the female minority in a male-dominated, male chauvinist environment. They did not know about the scars (or, to be less dramatic, repercussions) that such an experience might have, because they had not thought to ask, and no one had thought to make them uncomfortable by telling them.

While discussions about such experiences were commonplace amongst my female groups of friends, they rarely surfaced when we were in mixed groups.

I left dinner feeling both heavier and lighter. It was a sober reminder of how far society has to go in terms of challenging the normalisation of rape culture and objectification of women. And particularly how much more proactive my alma mater—a traditionally all-male, missionary school that sits at the nexus of social, economic, and political power, both institutionally and in its student body (if you have a school in mind, you’re probably right)—needs to be in remedying this poisonous culture.

After the dinner, I thought about the generations of female students that have passed through this school in two-year cycles, brushing off the slightly uncomfortable awareness that in some ways they were objects beholden to a culture they had no power to challenge, and still graduating with precious memories and treasured friendships that would last for decades to come. I am one of them. Perhaps we held the silent burden of scrutiny, self-consciousness, or even subjugation while at school.

Perhaps we still do.

In 2019 and 2020, Singapore was rocked by a steady stream of sexual violence misconduct cases perpetrated by university students.

There’s also a growing awareness of Singapore’s online subculture of ‘incels’—‘involuntary celibates’ who simultaneously revel in violent anti-women hatred, and objectify them.

SG Nasi Lemak, a now-defunct Telegram group that traded pictures of teenage girls for sexual gratification, is emblematic of this, but there are plenty of other private accounts, more lowkey Tumblr sites, and other platforms that operate in the exact same currency. I know, because I know for a fact that my image is one of those traded goods, along with those of many of my closest friends.

It was pretty revolutionary for me, and set me on a journey to interrogate the construction of masculinity that shaped the culture I’d been immersed in for the previous two years, and indeed the broader landscape of gender dynamics across single-sex schools that had operated in the background of my life until that point.

When I read that book, I was being pursued by a male classmate who’d been known to bother girls with inappropriate overtures while we were in school. I became convinced that he was an ignorant victim shaped by a culture that normalised the objectification of women, and sought to educate him by commending him to read Katz’s book. It didn’t work—he thought my attempt to engage him was an indication of interest, and pursued me for at least another year (even after I had left Singapore).

When I’d just graduated from this school, I felt strongly that our school ought to take first steps toward deconstructing toxic masculinity, by having some kind of moral ed or character development class questioning assumptions of what ‘being a man’ means and offering positive masculinity as an alternative. I still do.

Michael Ian Black, an American comedian and author, wrote that “It’s no longer enough to ‘be a man’—we no longer even know what that means.” To interrogate the amorphous ideal of masculinity in the classroom would be to ask questions like: What does it mean to be a good man? What does it mean to be a real man? Have you ever seen your dad cry? What is a stereotype, and why do we form gender stereotypes? Why do we feel uncomfortable discussing what girls and boys are supposed to be, and how can we reckon with reasons for that discomfort?

The objective of such a curriculum would not be to tell boys what they should or should not do. Rather, it would be to spark introspection and conversations amongst children, encouraging them to question internalised societal assumptions from an early age. It would be to provoke them to kindness and compassion by recognising a fellow male’s humanity, regardless of how different his counterpart might be from the ideal ‘real man’. It would be to encourage them to be comfortable with their vulnerability and not be afraid of their feelings. The questions such a class would ask have no easy answers, but arriving at answers needn’t be the point of education.

I know now that things are not that different. I am disappointed, but not surprised. Growing up in the social jungle of Singapore’s schools, it’s clear to me where these myths started, and how they were allowed to fester. Our youth cannot go through years of formal education without being guided to think about gender respect. I refrain from using the language of ‘teaching’, because a moral sensibility cannot be internalised through rote learning. The best our education system can do is to probe our young to think about such values at an early age, and then continue to positively reinforce it throughout their development.

It must start with the institutions in which we are first socialised. Shailey Hingorani, AWARE’s head of research and advocacy, suggests the introduction of school syllabi to challenge young people’s thinking on gender roles, and the consequences of unequal power in relationships, and economic and public life.

After all, it’s only been half a decade since I left school. It took Shirin Fozdar, Singapore’s first feminist advocate and Chan Choy Siong, PAP’s Member for Delta, a decade of campaigning and fortuitous political conditions to push the Women’s Charter Bill through Parliament. Between 1961 and 2020, it took us almost 60 years to acknowledge that the time has come in Singapore for another “cultural and mindset change” towards gender equality.

Those are nice words, but let us remember that it took decades of civil society advocacy, one too many ‘isolated incidents’ that have made their way to our courts and news headlines, and in recent years, bold individual women speaking up about their experiences, for us to arrive at this point of recognition. And it will take decades yet—of serious considered policy reform, working through difficult conversations like the ones my friends and I continue to have, and individual moral choices to speak more sensitively, think more empathically, parent in more principled ways—to effect that meaningful change being envisaged.

I was as vocally feminist as I could be in school. I still don’t think it was enough. In some circles of my contemporaries, years after graduation, I remain an object of gossip, speculation, dehumanisation. My worth will continue to be defined by how I look or the kind of things I post on social media. These are boys shaped by a culture whose silence condoned that kind of talk, but these boys also choose to remain mired in their ignorant privilege.

This is a personal account of a school, but also of a society. As I grow up I continue to deconstruct narratives of masculinity and femininity, deciding for myself what I can rationally subscribe to and what I’d like to discard for myself and challenge in communal spaces. I am doing what is within my power to mature as an individual. I look forward to our institutions, to our society, doing the same.