You’d imagine the life of a content creator to be glamorous. Their passion pays the bills, they get to fulfil their creative fantasies, and they might even lead a life of fame and prestige.

Yet the reality couldn’t be more different, because ultimately, the audience is king.

In today’s social media landscape, the author’s intent is invisible and inconsequential because a piece of work is judged by the people who consume it. A creator might believe they’ve created a masterpiece, but if it’s received poorly, who are they to contest the quality of their work?

If they intended one thing, only for it to have a completely different impact, does intention even matter?

In the case of the recent e-Pay/PreetiPls saga, audience perception was everything.

Both works were controversial. The e-Pay advertisement has been scrutinised to kingdom come, and a plethora of essays regarding racism and the validity of brownface have been written. But most of us haven’t yet properly interrogated what made the Preeti/Subhas video so “blasphemous”: the use of vulgarities.

For most in my generation, vulgarities are a fixture of daily life. There’s not a single social circle I’m in where people don’t indulge in swearing, and F-bombs are dropped all the time like bird shit during avian transmigration.

Over a work lunch, I conducted a casual experiment and recorded a grand total of 7 fucks given in the span of an hour. So to many Singaporean Chinese youth, the first response by Home Affairs Minister K Shanmugam felt like a father chiding a child:

“Orh hor, you say four-letter word!” (very heavily paraphrased, please don’t POFMA me).

Okay but here’s the actual quote: “When you use four-letter words, vulgar language, attack another race, put it out in public, we have to draw the line and say, ‘not acceptable’.”

As an adult speaking to other adults, why all this tiptoeing that reeks of primary school chastising? Why the condescending, paternalistic vibe, as though Singaporeans are in need of sheltering from the tyranny of the uncensored f-word?

The video wasn’t offensive to us young adults. We understood the phrase “fuck it up” as targeting racist actions by Chinese people, rather than pointing at racial identity itself. It wasn’t “Chinese people are fucked up” or “Fuck Chinese people”. It was a crass but true observation insofar as a majority race benefits from strength in numbers, causing a power imbalance invisible to them but that perpetuates casual and institutional racism.

But for a significant subsection of Singaporeans, it remains utterly unacceptable to say ‘fuck’ and ‘Chinese people’ in the same sentence. People like my father.

Growing up in my household, I learned to alternate between being a fountain of profanities and a model son because of how angry he could get at hearing swear words.

Once, my best friend casually said ‘fuck’ in my room while my father was right outside. He immediately threatened to throw the then seventeen year-old—who had grown up with me since birth—out of the house.

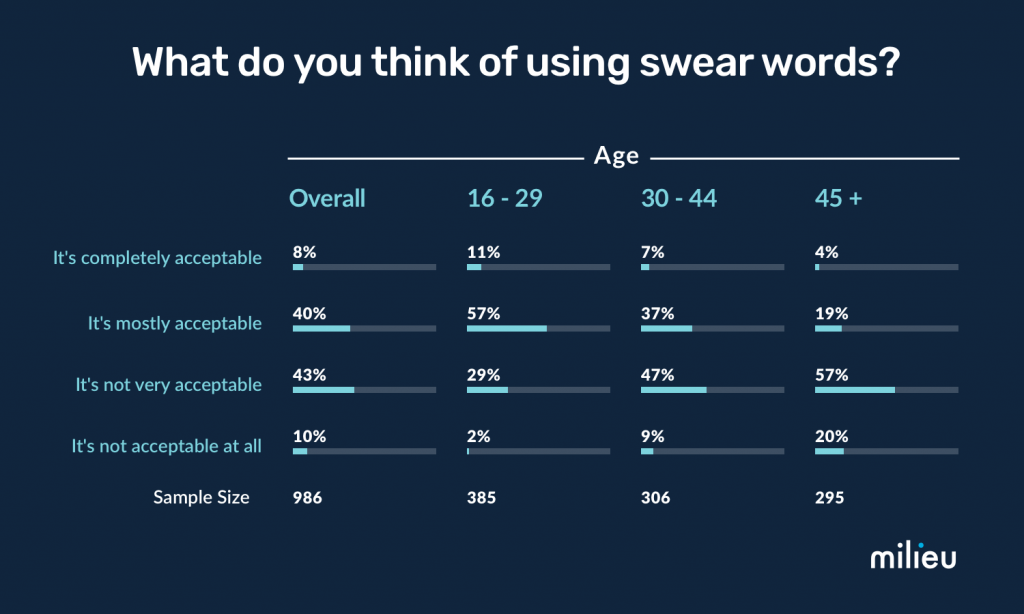

To find out Singaporeans’ attitudes towards swearing, we conducted a survey with independent research company, Milieu, on the topic. When the resulting data is sliced through via other indicators like gender, religion, and education or income level, attitudes remain mostly consistent. But the largest disparity is amongst age groups.

Results show that being older correlates with one’s disapproval of vulgarities.

While 57% of 16-29 year-olds find swearing “mostly acceptable”, 57% of 45+ year olds find it “not very acceptable”. Compared to the 2% of 16-29 year-olds who find it “not acceptable at all”, 20% of 45+ year-olds feel this way.

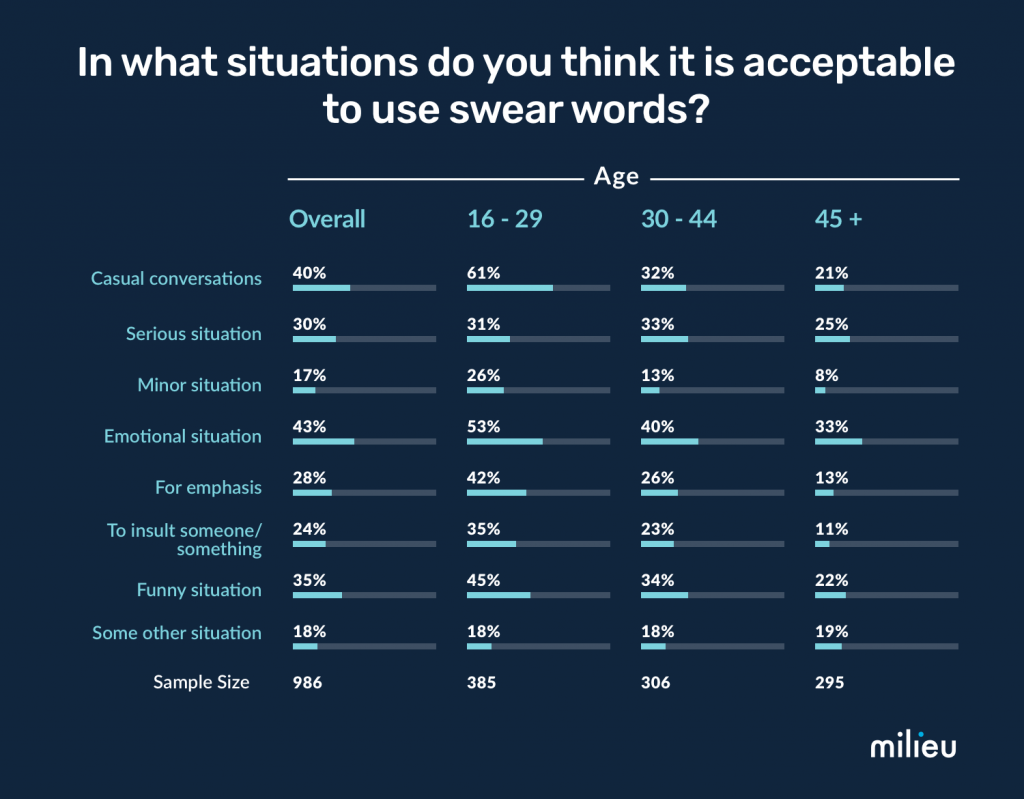

These attitudes match the survey results. Amongst 45+ year-olds, the most acceptable context for swearing is emotional situations, situated at 33%. As for casual conversations, 61% of 16-29 year-olds find it appropriate, while only 21% of 45+ year-olds do.

“It’s a very American thing to use vulgarities casually,” my father tells me. “As Chinese people, we’ve been brought up to not be so careless. Haven’t you?”

I let out a low whistle, because this hasn’t been my experience. I heard my first ‘fuck’ at the bright young age of 6, and I’ve never looked back. So I ask them—both immigrants from across the Causeway—if they ever heard swearing when growing up, or even as adults.

“Some of those naughty boys in school,” my mother concedes, grinning as she reminisces. “Otherwise, no.”

My father echoes her, but he’s stricter; adamant that he’s never heard vulgarities used casually his whole life.

Yet this apparent division between conservative Asians and foul-mouthed liberal Westerners is—if you’ll excuse my Anglo Saxon—a bunch of bullpucky!

My Asian best friend is comfortable with candid swearing because he can do so in his own household. His father, in particular, bonds with him over crude humor. I often catch them snickering over a George Carlin segment or Hokkien rap parodies from his father’s adolescence.

They’re no multi-generational ah beng family, but a model middle class university-educated Buddhist-Chinese one. His parents come from the same hometown as my mother, and both our mothers went to the same secondary school. They’ve all had similar upbringings.

If you want to nitpick at any divergence, we can: both sets of parents went to college on different continents.

Thing is, my parents were the ones who studied in America and Canada. My friend’s dad is an alma mater of NUS and his mother graduated from Japan. Conservatism and liberalism are not synonymous with the East and West.

“They have used the language of resistance in America,” Shanmugam stated, referencing the swearing in ‘K Muthusamy’.

Sorry if I didn’t get the memo, but is swearing exclusively American now? As if vulgarities don’t exist in Asian languages or any other language besides English. As if pun-based profanities haven’t been used explicitly as a tactic during the Hong Kong protests.

Shanmugam’s fixation on the ‘four-letter word’ (you can say ‘fuck’ or ‘the f word’ sir, it’s okay) is curious, having brought it up in previous instances like the banning of Watain.

Although there are those who disapprove of its usage, many use it in daily conversations. ‘Fuck’ and similar words are a part of Singaporean culture, not some alien parasite to be deflected.

As a young adult, I’m often frustrated by the moralising of older generations. There is an urge to compel them to get with the program or get left behind. But if the ultimate goal of discourse is to champion a society inclusive of everyone, we can’t write off the elderly.

While lashing out with a swear word here and there allows for the cathartic release of pent up emotions, its benefits must be weighed against its cost. Incivility—as Sheri Berman defines as including “invective, ridicule, emotionality, histrionics and other forms of norm defying behaviour”—is counterproductive to open and inclusive conversation. It signals ill will; a provocation of greater violence to come.

And again, incivility is a matter of perception, not intent.

Incivility causes its targets to be defensive, making them more hostile and further polarising their views. It spreads widely, alienates bystanders, and erodes faith in our public institutions. It’s more often than not a no-win scenario.

As public figures with a platform, content creators especially have to be mindful of the repercussions of their actions. They’re held to a different standard of responsibility because of how far their influence extends. In a world where we’re constantly in our filter bubbles, it would do us good to have alternative viewpoints to vet our work.

We can still swear when around people who are alright with it. But if you’re putting yourself out there, that’s a whole different story.

Form is function, and we should speak with the understanding that society as a whole will be our witness.

Our country prides itself not just on being a multiracial nation, but a diverse one. We scorn homogeneity, and rapid modernisation in tandem with unparalleled media access via the internet have allowed us to live very different lives from our elders.

As a result, our collective cultural consciousness is fragmented, and increasingly polarised. The state of discourse in the wake of the e-Pay saga showed this clearly. We’ve talked about what not to do, but we need a different way of expressing ideas and sentiments to each other. We need to learn how to agree to disagree.

If we are to find any common ground, it will be not through dismantling lived experiences but integrating new ones.

You cannot tell someone that their feelings are wrong. You would have as much success convincing a sad person that they’re not sad. There is no quicker route to having someone closed off to changing their mind than invalidating their feelings.

Some people found the e-Pay ad offensive, some didn’t. Some found the rap video offensive, some didn’t. The key is to not dismiss these contrasting viewpoints, because they’re not invalid—they’re incomplete. When faced with experiences different than ours, we should assimilate them into our broader understanding of the world to live as kinder, more well-informed citizens.

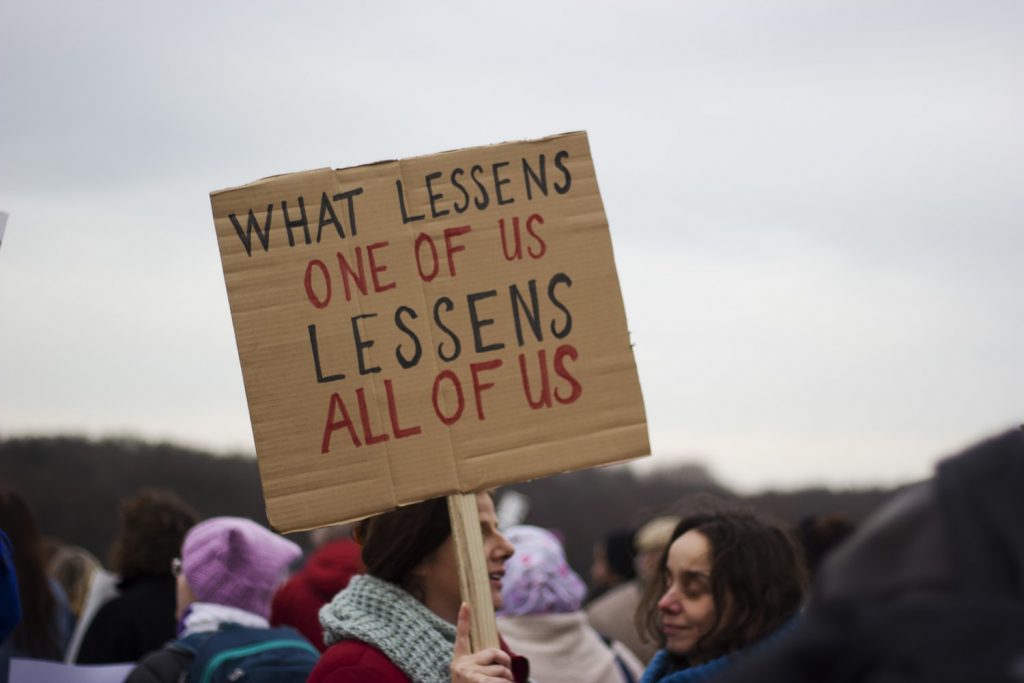

We should stop targeting feelings and desires. We should instead interrogate the actions that follow from these feelings, as well as the wider societal structures that influence these feelings.

This is as much about being sensitive to the older generation’s discomfort with vulgarities, as it is about empathising with minority experiences—or any issue where there is a wide divergence of experiences and feelings.

For example, you could read Alfian Sa’at’s lengthy post on feeling unsafe as a minority in Singapore, and feel like you disagree. And that’s fine, because you’re not Alfian, nor do you share his lived experience.

But are you going to lash out and refute his claims citing how it’s untrue from your perspective? Or are you going to take the time to empathise and understand his point of view in order to better advocate for minorities? Are you going to shrug and brush off Alfian’s experiences as an unfortunate part of the world? Or are you going to interrogate the larger social forces that make him feel like an outsider in his own country, while you feel perfectly safe and at home?

It’s an incredible amount of emotional labour that we will have to undergo to understand people different from us. We’re going to have to speak up, and speak thoughtfully, even if we fumble and fuck things up.

But we have to do this if we want our cesspool of a discourse to go beyond mouth frothing, pointing fingers, and wanting to attack and defeat others. We need a framework of widening our understanding.

Maybe one day I’ll be able to say ‘fuck’ in front of my dad, and he’ll get it.