All of us know that the media’s been saturated with discussions on race, so while we’re at it, we thought we’d update you on a different, more lighthearted topic: sexual violence.

You thought we’d forget, huh?

While we did call NUS incompetent over the way they handled the Monica Baey incident, they did promise to clean up their act. They even put a whole committee together, surveyed the student population on how to address the issue, and meticulously updated students and staff throughout the process.

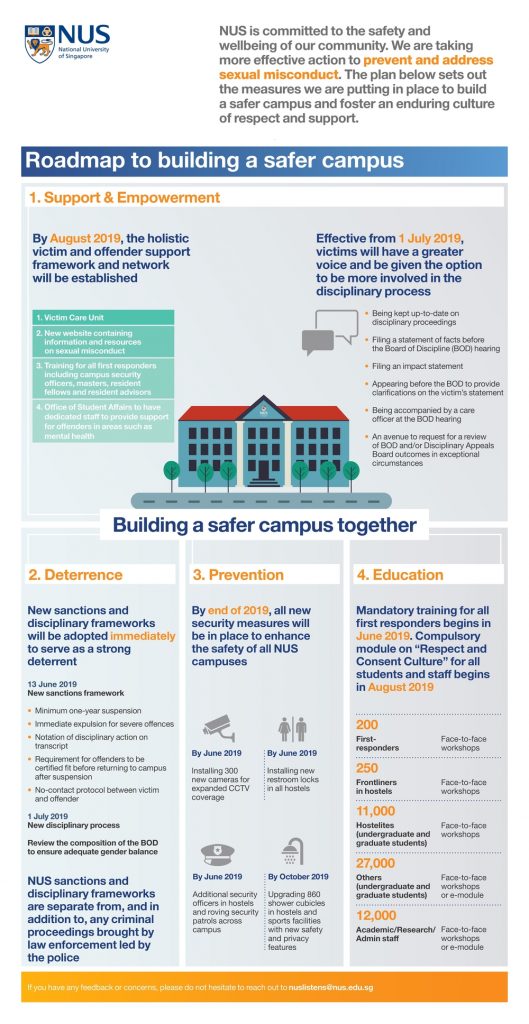

NUS is finally moving forward in their response, so it’s time to review whether they measure up to their promises. What’s their answer? This roadmap:

And so it surprised us to see that NUS has decided to … enforce a compulsory module on ‘Respect and Consent’ for the entire university.

*big sigh*

The best way to ensure no Singaporean does what you want them to do, is by forcing them to do so.

Since time immemorial, we have hated being told what to do. Despite this, the “father knows best so just do it” mentality has trickled down from our state to its various institutions, even though such efforts often backfire. This happens especially when young adults—arguably one of the most recalcitrant demographics—are the target audience.

Look no further than the SGSecure debacle. Servicemen were forced to download the application, and allegedly threatened with late bookouts or punishments if they didn’t do so. The result? Hundreds of terrible ratings with the NSFs displaying their displeasure, and many didn’t even understand what the app was supposed to do.

Even the good reviews are mostly fake, each of them pieces of satire that strain the imagination to conceive.

Should consent education be just as trivialised?

It doesn’t look good: students look to these modules with disdain and find them burdensome. Many are only willing to do the bare minimum, especially if it doesn’t count towards their grades.

Xiuwen, a third year student, tells me that she feels that the execution of such modules is bad. She understands that compulsory modules exist because NUS believes such skills are important. But lacklustre teaching causes students to come out resenting such content even more.

“These preallocated modules feel like a hindrance to exploring what we actually want to pursue,” she says. “It doesn’t help that many of these modules have a bad reputation. If my senior tells me ‘oh GER—Quantitative Reasoning—sucks’ then when I get GER, my mindset is automatically ‘shit’.”

On top of this, having to educate a student body of 36,000 is no joke. Needing the curriculum to adhere to a one-size-fits-all standard is why such efforts fail. To that end, content is always delivered through e-lectures, and remains rather rudimentary. But students still struggle because it’s nigh impossible to tailor your pedagogy to thousands of students across faculties and disciplines.

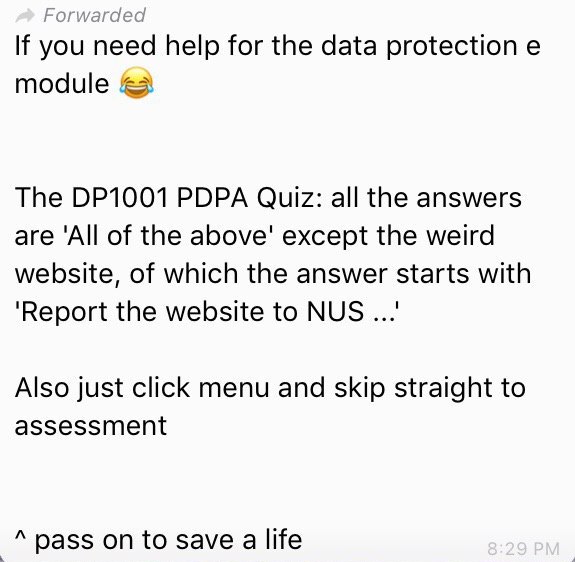

My instinct is that ‘Respect and Consent’ will be a lot like another module, DP1001.

If you’re an NUS student and you have no idea what DP1001 is, you’d be forgiven. It’s so forgettable you probably don’t remember it was called NUS Data Protection & PDPA Guidelines.

How was it carried out? Through a series of e-lectures in five sections, and then an MCQ quiz on which you had to score 90% to pass.

And absolutely nobody cared about it.

“If you’re a busy uni student, you just see and copy,” says Xiuwen. “It’s hard to take something seriously when the school doesn’t seem to take it seriously themselves.”

The e-module segment of NUS’ consent education is likely to go down the same route. Students will take the easiest way out, move on with their lives, and nothing will be learned.

It’s a shame, because it’s genuinely impressive that over 11,000 hostelites will be able to have face-to-face workshops! The few I’ve talked to who’ve already gone through the 2-hour workshop found it insightful and engaging.

But it’s still not enough.

“Certain issues like these aren’t just solved by a module,” Xiuwen tells me. “It makes me feel like they [NUS] aren’t giving this sufficient thought, or that they’re thinking on a super surface level.”

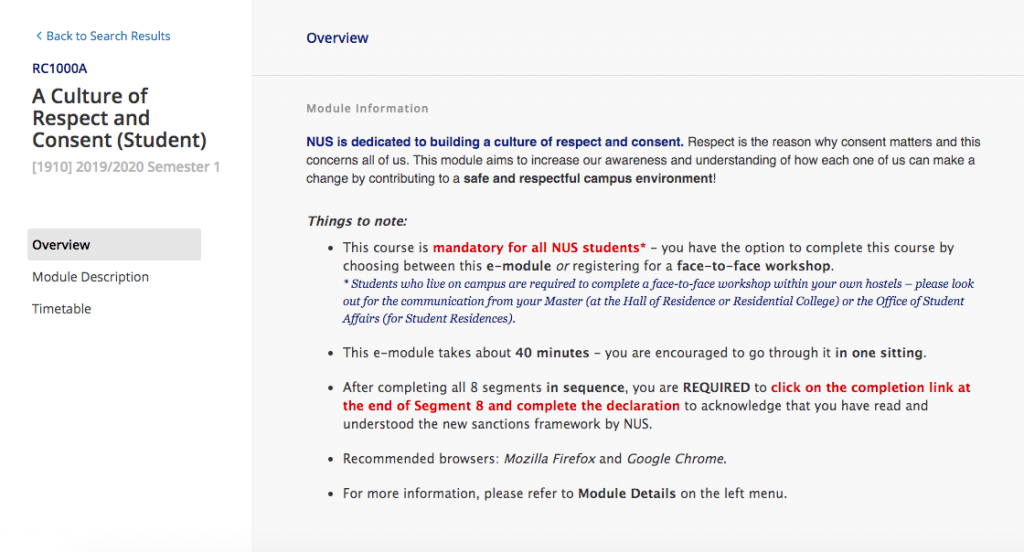

Looking at the text stressed in red: students must declare that they understand the new sanctions framework by NUS. In light of this, the module’s mandatory nature takes on a different meaning.

If there isn’t any nuanced discussion on consent within a 40-minute e-module, people are still going to stick to their biases. So this module just feels like a way to ensure that all students aren’t ignorant of future disciplinary measures. Should sexual violence ever be committed on campus again, students can no longer claim that they didn’t know the boundaries of sexual misconduct, nor contest punishments as ‘too harsh’. Because they should’ve already completed the mandatory module.

In this way, this module is a lot like a ‘Terms and Conditions’ document people tick before they sign up for a service. These students are already in university, so there needs to be some way to ensure that everyone is on the same page. What better way than a module that students are forced to take before continuing with their academic career?

And like all ‘Terms and Conditions’, no one actually reads them before agreeing.

Don’t make it compulsory, but open the resources such that anyone who wants to learn can do so. Allow the motivation to be intrinsic rather than a heavy hand from above forcing you to care about the issue.

Then, stoke interest organically so that students find their own reasons to give a shit about consent. This can be done by democratising knowledge. Don’t just train first-responders and front-liners on why consent is important, teach them frameworks for conducting their own workshops. This decreases the strain of resources on the administration’s part. But more importantly, this allows facilitators to tweak the workshop to fit the various contexts and communities that they are a part of.

One-size-fits-all education is never going to work because the culture of a football team versus a book club will be drastically different. CCA and hostel leaders have a better understanding of the sentiment on the ground than external facilitators. Let them take the lead in telling their own communities why learning about consent is important, and then equipping the students with a foundation for understanding the issue. Allow our youth to engage their peers because they’ll be far more receptive to people they know than a bunch of middle-aged adults sitting on an education board.

Finally, consent education should not start in university. These are young adults, many who are already very familiar with physical and sexual intimacy. Sex ed—not of the Focus on the Family Abstinence Is Best kind—should begin as early as possible.

Teens are already getting it on. Telling them that what they’re doing is immoral will just make them do it more, and with little understanding about safe sex.

We should start even before puberty. Consent isn’t just about physical intimacy. It’s about respecting boundaries, about being able to have conversations about different people’s needs and wants. Speaking about consent should become a normalised part of culture, rather than hushed up because it’s awkward.

Like all conversations, consent education is dynamic and ever-changing. We’ll learn in kindergarten that it’s not okay to touch or hit others for attention. We’ll learn as teens that as fun as flirting’s uncertainties are, always ensure that you’re communicating with your partner. And we’ll learn as adults and beyond just how diverse people can be in their attitudes towards intimacy. We’ll learn how to untangle these desires and live together.

Respect and consent isn’t a module. It’s what we will all navigate throughout our lives.