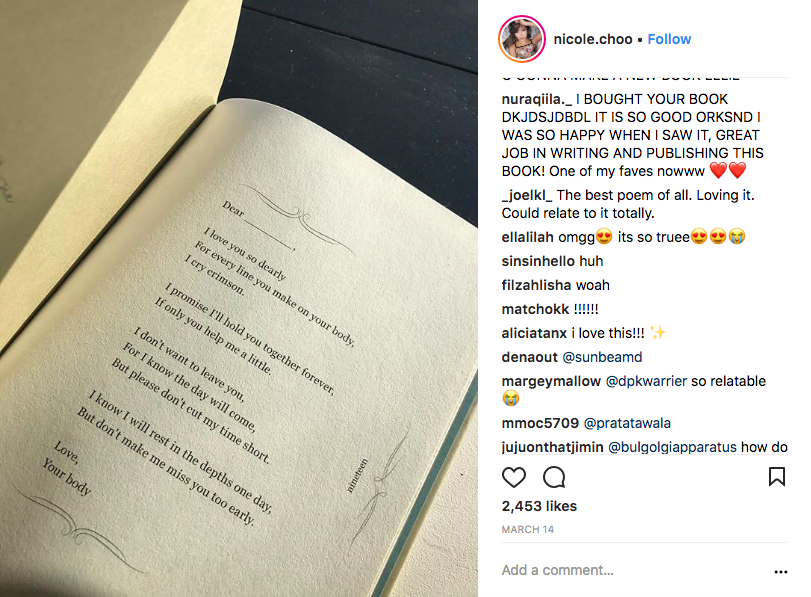

On March 10, as part of the BuySingLit national movement, boutique publisher Bubbly Books launched a book by social media personality Nicole Choo. Titled nineteen, the collection of musings “that range from anger, sadness and desperation to Love and Hope” was written “in the tradition of Lang Leav and Rupi Kaur”.

Almost as quickly as the book made the Straits Times bestselling list, criticism began to surface.

Of all the responses, a book-review-slash-comedy-roast on Youtube by Hirzi Zulkiflie and Dee Kosh (both social media personalities themselves) attracted the most attention. Their core contention: Nicole shouldn’t have released a book because she is not “qualified” to write poems.

When I reached out to Nicole, she told me that she welcomed any form of genuine critique on her writing, as she has a lot to learn as a new author. However, she declined to comment on the other aspects of the attacks against her.

On why she decided to write poems, she said, “Poetry for me is a form of healing. Writing poetry helps me to look at the bigger picture of a painful phase, and during the times when I have felt very down, in despair and harassed by people who try to tear me down, it’s given me an outlet and helped me as I try to make sense of the world.”

“I feel that it’s a beautiful way of connecting with other people,” she added.

While Dee Kosh declined to comment, Hirzi was much more forthcoming about the point they were trying to make with their video.

Over email, he explains that they made it simply because they found “Nicole’s work to be hilarious”.

He elaborates that “I think it was the pretentiousness or claiming the label a poet,” and that he thinks “the work didn’t speak for itself”.

For many who have criticised nineteen, this is what it’s all about: an influencer who has no right to call herself a poet attempts to capitalise on her 97,100 followers to sell books.

At the same time, who gets to decide whether Nicole Choo’s poetry is any good?

Eliza Teoh, a director at Bubbly Books, tells me, “We want to change the minds of young people who think poetry is not for them because they won’t relate to it or understand it. Nicole’s poems were everything were were looking for. Engaging, heartfelt, inspiring, and uplifting.”

“Since nineteen was published, we’ve seen an increase in the number of submissions from aspiring teen authors and poets. We’re really happy that we’re helping to cultivate a culture of writing. Writing should not be seen as the realm of the privileged few or only for those who have a formal education in the area,” she adds.

When I reach out to Singapore’s Youth Poet Ambassador Pooja Nansi, a poet, spoken word performer, and educator, she says, “You can’t complain about not enough readership for poetry and then also complain when readership finds the poetry it wants. You cannot demand that readers love the poetry you think is worthy.”

On who should be “allowed” to write poetry, she has this to add: “There is space enough for all of us … I am not interested in safeguarding language and saying that some of us are allowed to participate in using it more than others. That is bonafide elitism.”

“We all deserve the right to creativity. We deserve the right to express ourselves,” she stresses, “We also have the right to choose who we read, but not the right to choose who others read … I think we are better off spending time making than tearing down.”

First, to dismiss the work of Tumblr and Instagram poets as shallow and hence less deserving of attention is to miss the point.

I was more or less raised on books, and even went on to earn a university degree in English literature. Accordingly, I have slightly different (and subjective) standards for what I consider to be poetry I enjoy.

At the same time, my experience is a privileged one—one that an outsized proportion of Singaporeans neither share nor have access to. As Eliza tells me, “I heard many young people say that her book, nineteen, was the first book they had bought in years. I think that’s wonderful, that nineteen is reviving an interest in books and poetry in youths.”

Samuel Caleb Wee, a writer and MA student at Nanyang Technological University, echoes her sentiments despite admitting he’s not particularly a fan of Nicole’s work: “A young person who’s never had the luxury of poetry in their life might … find that she speaks to a part of their existence they’ve never had described before. That’s still powerful, for them. I think it’s a tad unkind to take that first encounter with language away from them, on the grounds of the poet being too famous or too shallow.”

As this tweet also points out both succinctly and eloquently, these differences in appreciation only serve to highlight the gaps in our education system.

Between 2013 and 2015, the Straits Times ran a number of stories reporting on on how fewer students are taking literature as a subject. This trend has only persisted, and it has become clear that there is a lack of equal opportunity when it comes to access to the arts and humanities.

This isn’t to say that we should all learn how to appreciate one type of poetry over another. But we do have to be wary that criticism of “less serious” work isn’t really just thinly veiled elitism.

Hirzi justifies his video with this example: “Do we question Tina Fey or Trevor Noah when they critique and joke about bad decisions that President Trump makes … no we laugh along.”

I don’t think this is good enough.

For one, the savagery and explicitness of their commentary, a lot of which came uncomfortably close to sexual harassment and cyberbullying, made the video resemble a vicious attack more than a comedy roast or a book review. As much as Nicole Choo isn’t a helpless child, she’s not an untouchable, 70-year old politician either.

Hirzi argues, “That’s a comic’s modus operandi no? To laugh at things laughable.” To this, I would gently suggest that with their over-reliance on slapstick humour and vulgarity rather than wit or insight to carry their jokes, they could afford to take a few lessons from Ali Wong.

But this aside, the video underscores how our collective disdain for the now-typical young and pretty influencer has reached a pinnacle of sorts, and we’ve forgotten that behind their hyper-curated Instagram accounts are actual people.

We need to realise that the influencer industrial complex is evolving. From clothing lines to creative agencies (and now books), social media personalities will keep finding new ways to express themselves, all while also ensuring they stay relevant, popular, and financially secure.

As such, why attack them as individuals when there are far more pertinent conversations to be had? Why not take aim at how social media’s promise of validation is shaping the younger generation’s behaviour online? Why not question whether social media influencers truly have anything valuable to offer brands, and whether they need to be made more accountable?

To this end, their “takedown” of nineteen can only be described as mean-spirited and masturbatory. I would even go so far as to say that it fuels anti-feminism and a culture of hate.

There is comedy, and then there is hate. Whatever Hirzi or Dee Kosh’s intentions, and regardless of the “apology” video they released, the hate towards Nicole has risen to a point where she has begun receiving death threats.

Therein lies a lesson for the rest of us: if we want to criticise influencers, we cannot do so while actively ignoring both the culture and industry that continues to reward and empower them.

Yes, influencer bashing is fun. But social media influencers have also been around long enough that for those who want genuine change, it should be clear that using their mere existence as justification for belittling them is no longer meaningful or consequential.

At its heart, this whole thing about Nicole Choo and nineteen isn’t really about good or bad poetry. Rather, it’s just another cliched manifestation of our irrational bitterness towards influencers. Had it been someone else who had published nineteen, you can be sure the response would have been radically different.

Nicole shares, “I wanted to encourage my readers to pen down their feelings like me. You don’t need to feel that writing is beyond you … there’s never a right or wrong to your writing; if it helps you and makes you feel better, that’s all that matters.”

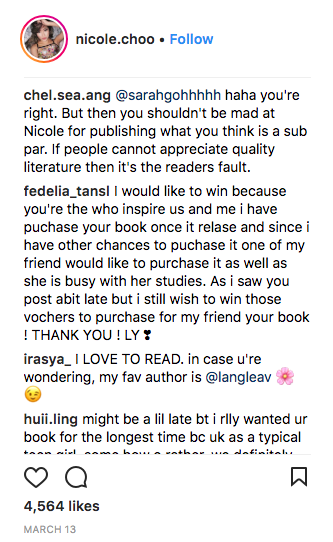

And the reality is that there are readers who like Nicole’s work, and who think it’s good. As evidenced from comments on her Instagram account, more than a handful of individuals have said that her poems spoke to them.

In light of this, Samuel offers some perspective: “Look at it this way—the form of poetry you’re talking about here … is it a carcinogenic?” It may be “low in fibre content, possibly high in fructose,” but so is “advertising”, “political activism”, and “religion”.

His point, in essence, is that everything is subjective. And what he considers “not very nutritious” may in fact be someone else’s deeply held truth.

That’s perfectly okay.