Petition-making has lately become Singapore’s favorite form of democratic mobilisation, from calls to ban PMDs, urge more comprehensive action on sexual violence, and introduce a plastic levy. These petitions become even more visible during debates on LGBTQ issues, such as during last year’s Ready4Repeal movement and countermovement.

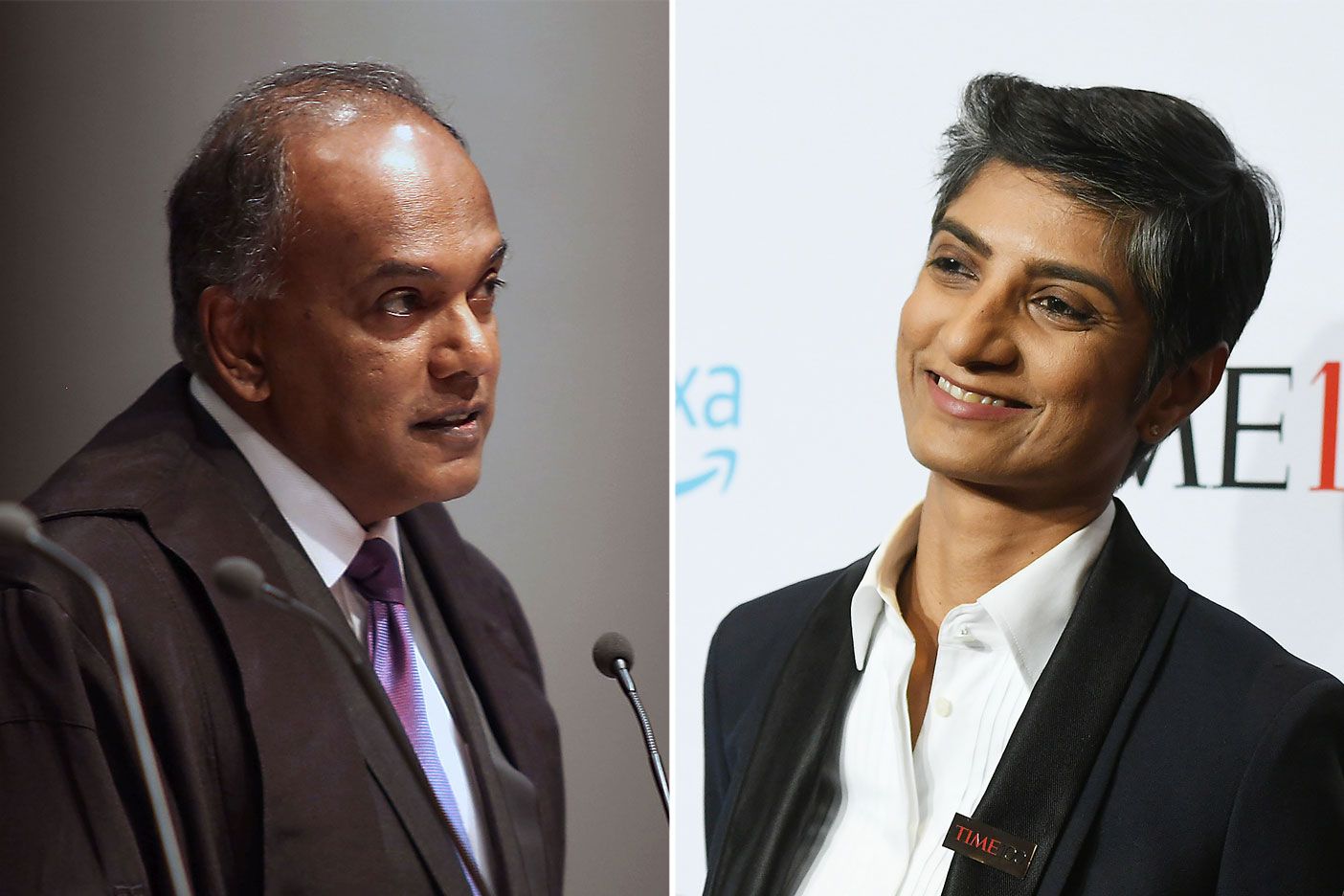

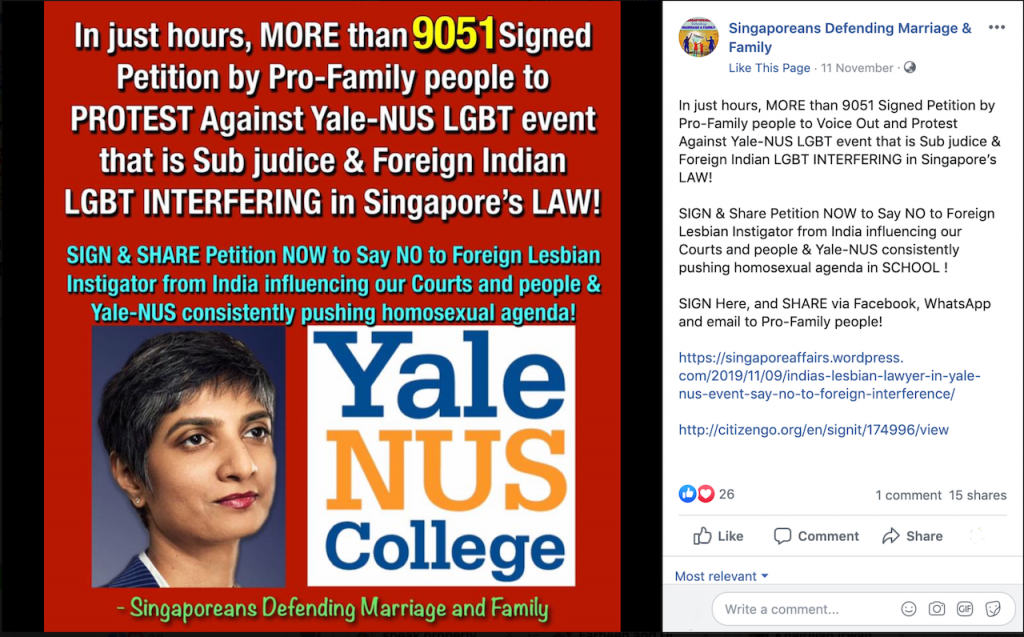

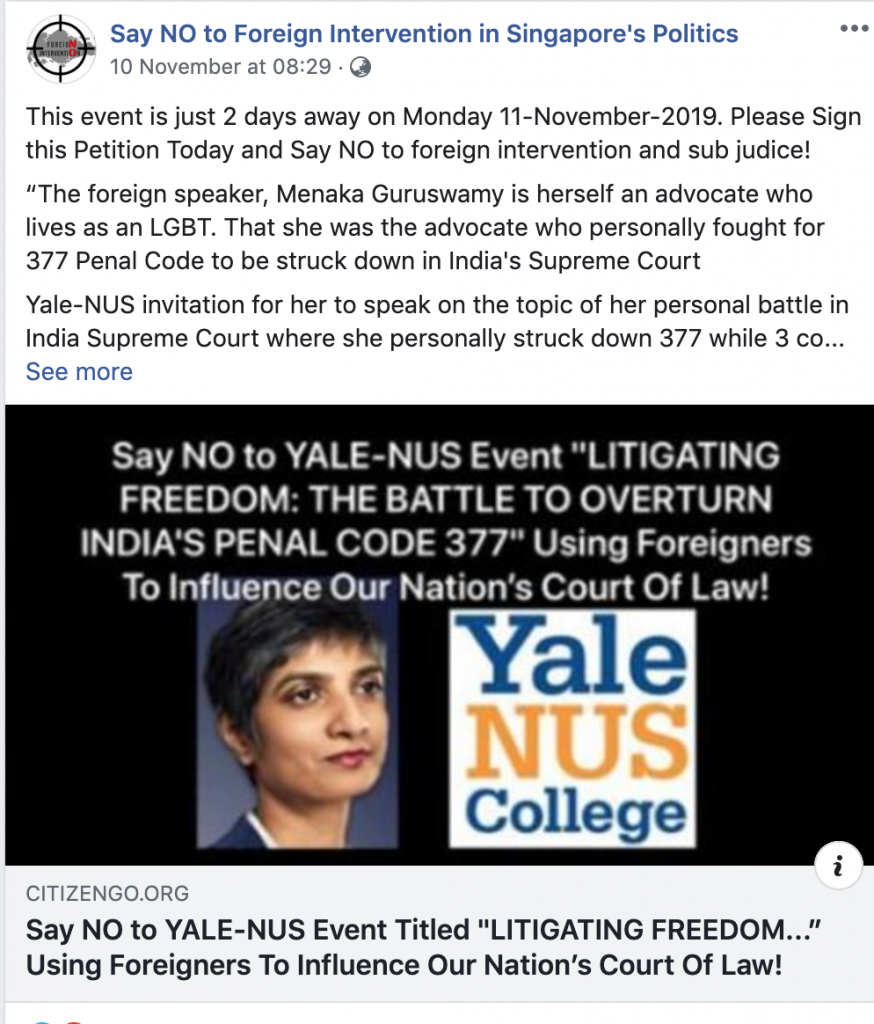

Most recently, a petition called for the cancellation of Dr Menaka Guruswamy’s November talk at Yale-NUS College on repealing India’s section 377. It claimed to represent the “citizens of Singapore”, while describing Dr Guruswamy as a “Foreign Indian LGBT INTERFERING in Singapore’s LAW!”. The petition allegedly collected 10,000 signatures in three days, and was significant enough to warrant a mention by our Minister for Law, K Shanmugam, in his statement regarding the event.

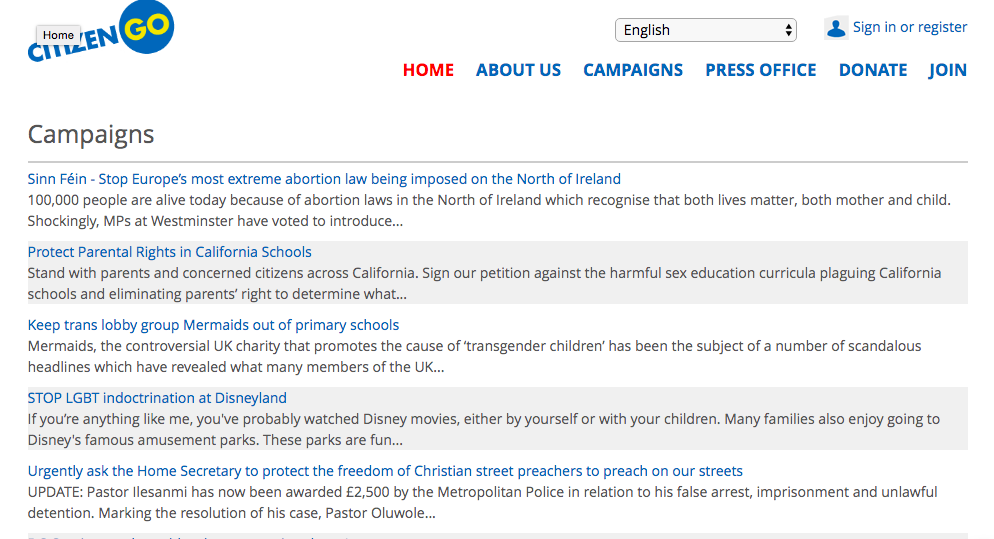

The anti-LGBTQ movement here frames its arguments in terms of fighting against “foreign intervention”, claiming to represent “Asian values” or the “true Singaporean”. Yet, this petition points to how their rhetoric and strategies are heavily borrowed from the West. In fact, members of the public have no way of knowing how many signatures were actually registered by local Singaporeans.

In comparison, last year’s Repeal 377A petition, which recorded 50 000 signatures, ensured the integrity of its petition by using GoPetition, which required signatories to declare their postal code and nationality. The numbers recorded in that petition not only reflected the ground better, but also allowed it to be submitted to the Penal Code Review Committee and local Members of Parliament.

The pro-LGBTQ camp is constantly challenged for not being Singaporean enough. Thio Li-Ann memorably said in 2007 that repealing 377A would be copying “the sexual libertine ethos of the wild wild West.” In recent years, groups like We are against Pinkdot in Singapore frequently bought up the presence of MNCs sponsoring Pink Dot as a form of “foreign interference”, which may have led to the 2016 ban on foreigners and foreign funding for events that take place in Hong Lim Park, including Pink Dot. The spectre of foreign interference looms large over any discourse promoting LGBTQ rights, to the point where we miss the reality that the anti-LGBTQ movements are just as influenced by foreign discourse, if not more so.

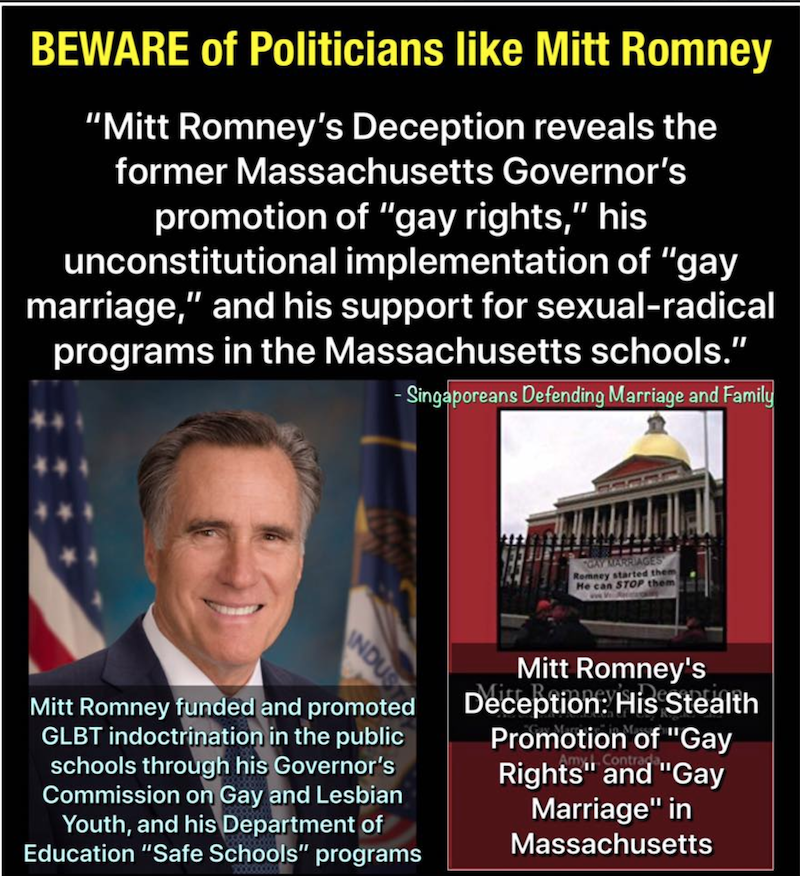

A quick glance through We Are Against Pinkdot and Singaporeans Defending Marriage and Family brings up dozens of posts bashing, amongst other things, American politician Mitt Romney and Swedish environmental activist Greta Thunberg. Despite representing “Asian values”, these pages fixate on the rhetoric of American politics, far more so than LGBTQ pages such as the Pink Dot facebook page. The discourse of LGBTQ rights and speakers being foreign funded ultimately obscures from the public eye the relationship between global ultraconservative movements and local anti-LGBTQ movements.

This does not mean we have to abandon these concepts altogether. Rather, we must critically engage with individual cases and not assume “localness” or “foreignness”.

In CitizenGo’s case, claims to Singaporeanness provide a veneer of legitimacy where there is none. Nobody in the lecture theatre where Dr. Guruswamy spoke was under the impression that she was Singaporean or commenting on Singaporean politics. In contrast, the CitizenGo petition repeatedly frames itself as a representation of local voices speaking out against murky, hidden foreign agendas. If we are to go with the anti-LGBTQ camp’s definition of “foreign interference”, this could well be its ultimate manifestation.