Singaporeans are obsessed with grades. But after countless narratives about moving away from an over-emphasis on academic performance, we’re still stuck at square one with no results.

We haven’t figured out how to disrupt the rat race that causes our kids unnecessary stress. The inequality gap continues to widen between the haves who succeed with the wide resources available to them, and the have-nots who continue to lag behind their peers.

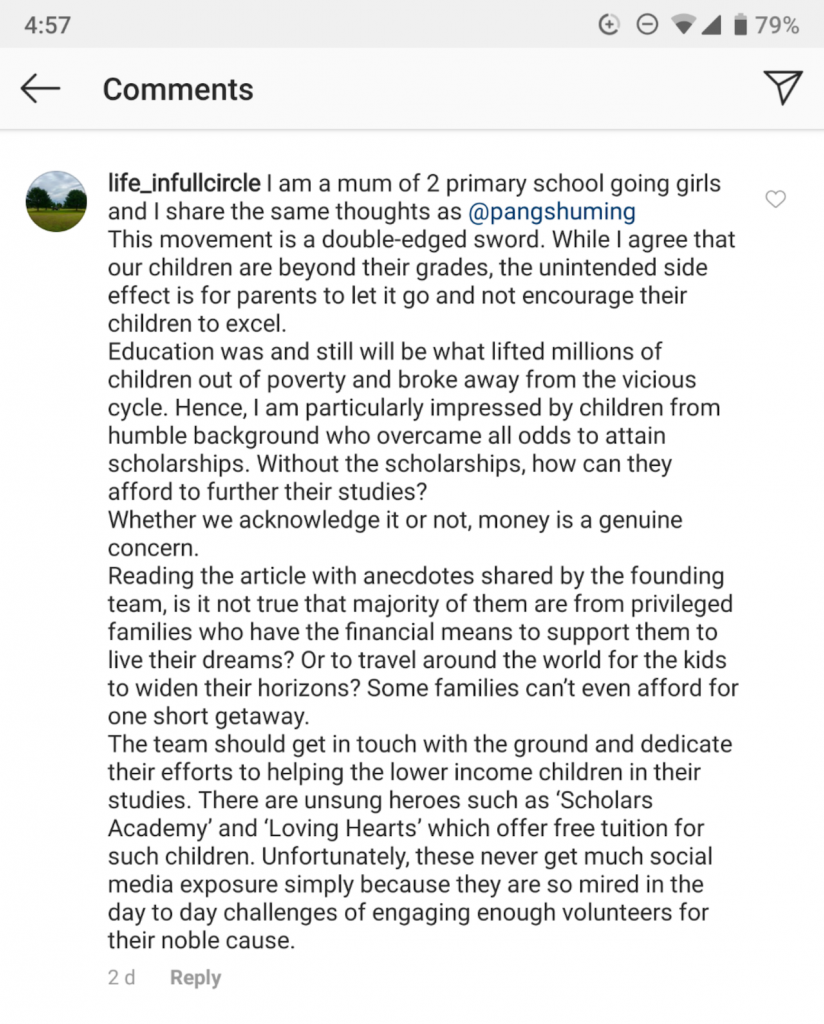

So when a few parents banded together to start a new initiative aimed at changing parental expectations with regards to grades, it should have been well received by the public.

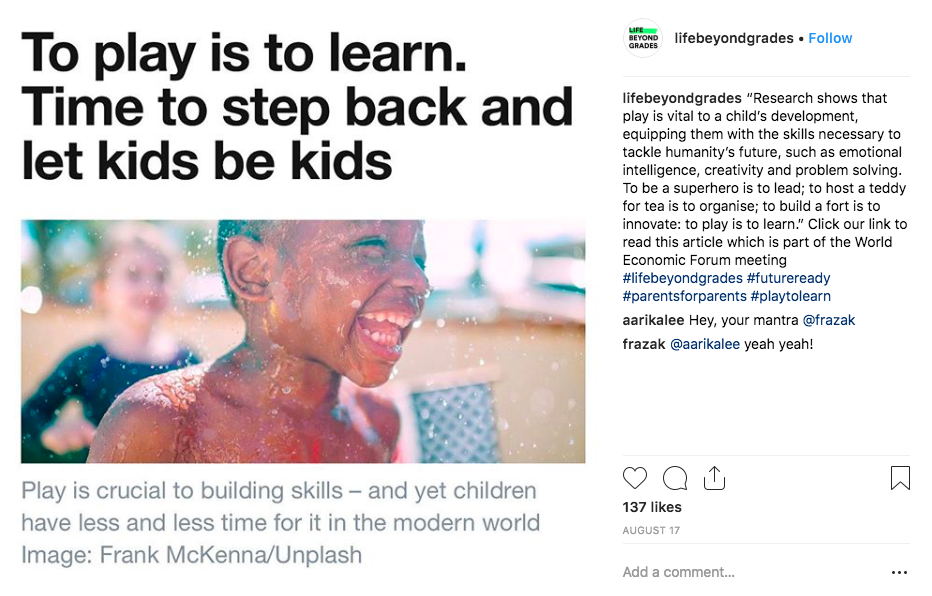

Give children more time to play. Cut down on tuition. Show them that grades don’t define who they are. This is the noble message that Life Beyond Grades champions.

Unfortunately, the initiative appears just as myopic in its strive to correct a narrow-minded societal attitude.

To walk the talk, the founders, who run their own media companies, are upfront about their ‘less than stellar’ PSLE scores. By making the distinction between the past and present, they hope to show other parents that their children don’t need good grades to succeed in life.

In reality, our family backgrounds significantly inform how we navigate the education system. We can preach that money doesn’t lead to success, but this isn’t a concept that low-SES families are familiar with. Their poor circumstances do have a substantial impact on their children’s aspirations and future.

Meritocracy, especially in Singapore, isn’t forgiving like that.

James, a media content strategist, shares that his father had been in and out of jail several times during his childhood. His mother, being the sole breadwinner of the family, would constantly drill him and his siblings on the importance of getting good grades. For his mother, getting her children to prioritise their results was the only chance at a better future for them.

They studied hard so they could escape their “crazy poverty”.

“Whenever I see stuff such as the Life Beyond Grades initiative, I’m like, bitch do you even know what privilege you all have? Up till now, I still believe that only rich people can make it in life,” says James.

He remains adamant that if he didn’t study hard, he would not be where he is today.

Reducing the pressure that children face is not as simple as telling them that grades aren’t everything.

Neither of them graduated from university. Before they got their current company going, they went from door to door doing sales just to try and make ends meet.

“Obviously they didn’t want me to live through the same kinds of struggles. It’s understandable that the only form of assurance of a better life is going down the typical path of success: get into a good school and then a degree,” says Benjamin.

After prioritising their finances for his intensive six-year pre-PSLE tuition regime, his parents’ expectations gradually changed when he got into Raffles Institution. Their family’s circumstances had also largely improved.

“They weren’t so hard on me for not doing well in school anymore, or not pursuing the typical ‘Big Four’ career path, as long as I did my best. Perhaps it was the combination of our financial situation and the peace of mind that an elite school’s education provided that gave them a bigger appetite for failure, risk, and the unconventional.”

While there’s nothing wrong with being born into privilege, to not address this privilege suggests some form of dishonesty, especially when one must consider the possibility that their children are already ahead of the pack before the race has even begun.

These families don’t need to survive on a monthly household income of $500, where their only chance to escape the poverty cycle is by hoping their children study hard, get good grades, and find a well-paying job.

They are not burdened with the fear that their children will turn to bad company, when they consistently fall behind their peers who score better than them in school. They don’t have to worry about being unable to afford exorbitant tuition classes for their children, nor have their children put up with an unconducive home environment just to finish up their school work.

Without all these worries, their children are free to explore other options beyond traditional academic pursuits. They don’t need good grades, because they are largely protected from the far-reaching consequences of coming from an underprivileged background and not doing well in school.

In a ‘meritocratic’ society, those with good grades stand a higher chance of survival. And those with the ability to achieve such grades tend to come from less “problematic” family backgrounds.

As such, we should focus on giving underprivileged and low-income families a leg up by finding ways to fight institutional biases.

MOE says it’s strengthening school-based programmes to assist academically weaker students and providing financial support for students who need help.

Perhaps introducing policy-level incentives that encourage tuition centres to offer free or low-cost classes to children from underprivileged and low-income families might be a way to open up more learning opportunities as well.

Irwin, who runs a General Paper tuition centre, says he’s waived or subsidised tuition fees for his students who come from challenging backgrounds. He acknowledges that price may be a factor in running an educational business, but he has “never let it get in the way of students who genuinely want to learn and benefit from [his] classes.”

Tuition isn’t just about having additional guidance in homework for these children. It’s also about finding a consistently conducive and safe environment where they are free to explore the pure joy of learning—without being hindered by a price point.

At present, those who can’t afford tuition but do not want to give up on learning turn to volunteer assistance and welfare programmes. One such volunteer-run community initiative is ReadAble. It addresses social inequality through creative methods of early intervention. Volunteers teach underprivileged children how to read, in order to close the literacy gap present between these children and their more affluent peers.

Initiatives such as Praxium and The Apprenticeship Collective expose secondary school students to various career paths through attachment programmes, apprenticeship programmes, and talks.

Our senior staff writer Grace volunteers with both programmes and appreciates the opportunity to mentor students from the ‘non-elite’ schools. If not for programmes like these, she says, less privileged students wouldn’t get the chance to envision multiple pathways to success beyond traditional doctor, lawyer, and banker stereotypes.

Louis, the founder of Praxium, says, “We see kids in higher SES families aspire to be lawyers, doctors, engineers, programmers, entrepreneurs and investors these days. From the lower SES strata, we see aspirations like truck driver, retail assistant, chef or DJ. That’s a function of the environment and exposure they have, and the mental ceiling they put on themselves.”

Yet this is also tricky, because a lawyer-doctor aspiration isn’t necessarily better than a truck driver aspiration.

Louis adds, “If we understand it like that, we revert to the same linear evaluation of paths in life. We may not pursue grades anymore, but we pursue income and prestige.”

While these ground-up initiatives may plug the existing inequality gap that exists in our education system, they cannot be the only resource that low-SES families rely on. This is especially so if the founders deal with their own financial challenges.

If there is no radical change within the system itself to encompass the needs of children from all walks of life, no amount of telling parents that their children should have more time to play or valuing and championing the “development of traits such as perseverance, passion, innovation and resilience” will alter the status quo.

So yes, the real takeaway from Life Beyond Grades just needs to be distilled correctly: students should gain the right skills and knowledge from learning, regardless of their scores.

But before that, it must accept that a conversation about how “grades aren’t everything” inherently excludes families who can’t afford to care less about grades in the first place.

[socialpoll id=”2541124″]