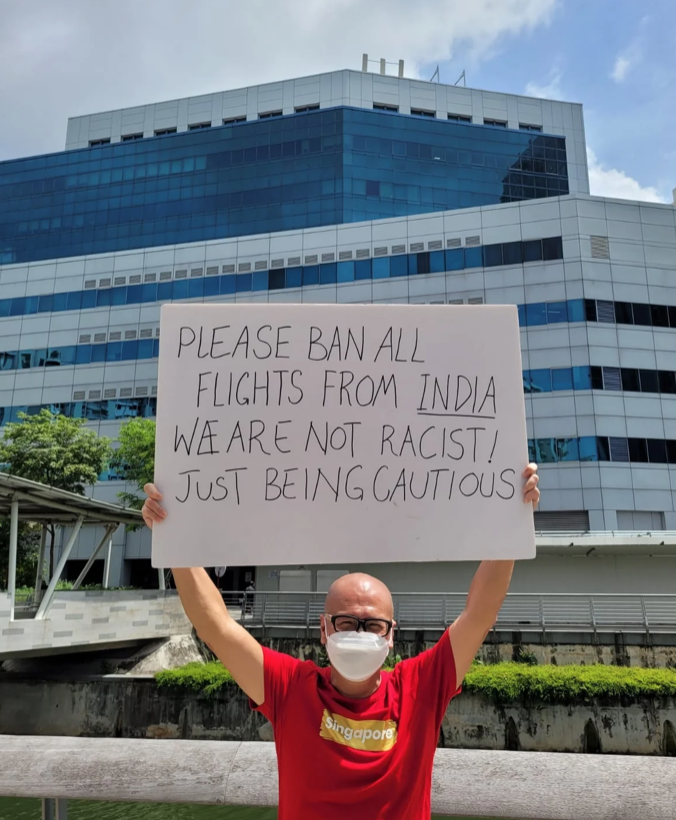

Image credit: Rogan Yeoh

We’ve heard a lot about xenophobia recently. From Gilbert Goh’s ‘protest’, to discussions of social cohesion in parliament, and viral videos of targeted harassment in public. In moments of national strife, for example a recession or a pandemic, there is a reflex to point to the ‘outsiders’ as the instigators of social problems.

It’s difficult to explain ‘xenophobia’ as a cultural event due to its shifting targets. Who receives disdain depends on the national moment. For example, today it’s travellers from India to Singapore. Tomorrow it’s the PRCs. Perhaps next week it’ll be the Caucasian expat or the Malaysian migrant worker.

Though xenophobia often feels fleeting and intangible because of these shifting targets, it’s important to note that it hasn’t just arrived on our shores. There’s a complex history of tension between ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’ in Singapore, and there are a few factors which play into this tension: the ongoing construction of a Singaporean national identity, unilateral policy making, and economic inequality.

Here are a few lessons from history that can help us contextualize the spike in xenophobia that we’re seeing today, and chart a way forward without it.

Recognise ‘survivalist’ rhetoric when it’s used, and reject the idea that foreigners & other countries are adversaries to Singapore.

From 1965 to 1980, the ‘ideology of survivalism’ was a major part of the national identity in Singapore. To rally the public behind somewhat unpopular growth measures (importing foreign talent, for example), Singaporean leaders often recalled the nation in strife in their public messaging.

The image of a divided, poor, and uneducated society was used to implore Singaporeans to accept new policies and reject the regressive ‘old ways’. Though this was intended to encourage citizens to embrace progress, it often inflamed tensions between the ‘insiders’ and the ‘outsiders.’

Case in point: tensions were high on the topic of foreigners in Singapore between 1970 and 1980. During this time, foreigners occupied a majority of the PMET roles. Many locals felt they were unable to compete with foreigners who received higher salaries. To be clear: these were real concerns. It’s not xenophobic to acknowledge income disparity and criticise policy.

The leadership response to this discontent was the ‘survivalist’ ideology. In his national day speech in 1980, Lee Kuan Yew called the younger generation’s approach to work ‘lackadaisical’ and suggested that they look to their forebears for examples of hardship, which would motivate them to excel. He also declared that skilled foreign workers would cure lacklustre job performance by encouraging locals to work harder.

Though this response is pragmatic, it doesn’t account for the sentiment of insecurity expressed by the citizens. Insofar as xenophobia is motivated by the ‘fear of the other,’ survivalist rhetoric which called Singaporeans ‘lazy’ and foreign workers ‘talented’ did not encourage friendly relations between visitors and natives. In fact, it contributed to the insider vs outsider problem which plagues us now.

Two things can be true at the same time: Singaporeans can feel that the government’s immigration policy is too robust while immigrants add value to the local economy. The presence of foreigners may trouble Singaporeans, but generally speaking, foreigners are not coming to Singapore to deliberately undermine the local talent.

In parliament last week, Minister Shanmugam expressed this duality in response to an increase of xenophobic outbursts against Indian nationals in Singapore. In some cases, CECA (an economic policy between Singapore and India) was used as evidence that the government is ‘complicit’ in bringing disruptive outsiders into Singapore.

Minister Shanmugam invited the PSP’s Leong Mun Wai to propose a Motion to debate CECA, instead of making generalisations about the issues which foreign talent contribute to society. “You know that most of what is said about CECA is false,” he stated. “Singapore is 725 sq km of rock. We have to make a living by being open to the world.”

Foreigners should not be labeled as a cause nor a solution for social problems in Singapore.

In the 1980’s, the declining birth rate was first acknowledged as a big problem. A proposed solution was to import more foreign domestic workers to encourage working women to have children. The proposal was met with strong opposition. In parliament, a debate was held about the ‘social problems’ that domestic workers contributed to society.

The specifics of these ‘social problems’ were not clearly outlined, but nevertheless, they were discussed, and also appeared in letters to The Straits Times. Some of the arguments against importing more foreign domestic workers suggested that they made Singaporean women lazy and unwilling to cook, clean, or take care of their children.

In this instance, an entire group of people (in all their multitudes and life experiences) were proposed as both a threat and a solution to a national problem. On the one hand, foreign domestic workers could encourage couples to procreate by providing physical labor. On the other hand, they allegedly weakened the maternal instincts of Singaporean women and engaged in dubious social activities.

The suspicion of foreign domestic workers and the need for their presence has increased in recent years. In 2014, plans to celebrate Phillippine Independence Day in Ngee Ann City were scrapped due to safety concerns following the vitriol against the event on social media. On Facebook, a group titled “Say No to An Overpopulated Singapore” rejected the event’s use of the word ‘interdependence’ and an image of the Singapore skyline.

Can we view foreigners as guests or visitors, not strangers?

What’s striking about the digital outrage towards the Phillipine Independence Day event was the specificity of the xenophobia in the Facebook group’s call-to-action. The umbrage that was taken with the word ‘interdependence’ was ludicrous given that the two nations are to some extent, well, interdependent.

Though this interdependence is at times problematic, the net positive for Singapore is that citizens have more leisure time, more children, and more elder care. Foreign domestic workers have an intimate job description: they live and work in our homes. Surely, we should view them as guests and not strangers who seek to corrode the social fabric of Singapore.

The semantic gap between the stranger and the guest is a driving force behind xenophobia in Singapore. As I’ve mentioned before, there are plenty of legitimate reasons why this has happened. It has even been encouraged in the past. But in modern times, when the world is multicultural and globalisation is inescapable, it feels more appropriate to host foreigners and not merely tolerate them. We can do this while also thinking critically about what function foreigners can serve in our society.

Perhaps the way forward is to interrogate our biases when we are feeling threatened, uncomfortable, or dissatisfied with the presence of foreigners. While writing this article, I returned to a question that I’ve learned to ask myself over the years: how can I express myself without hurting others?

On the structural level, those who are writing legislation with the potential to disrupt local livelihoods should take more care to explain their decisions while offering solutions to the growing pains. As Minister Shanmugam mentioned in parliament: much of what has been said about CECA on social media is untrue. So why isn’t an accurate account of the policy and its implications more widely known?

Additionally, there should be more opportunities for civilians to engage in policy making. Civic engagement is a critical function of democracy which (in general) is not emphasized in Singapore. With more dialogue between MPs and their constituents, perhaps misinformation on topics like CECA won’t spread and spark xenophobia in the first place.