The prospect seemed unlikely, until photos emerged of the People’s Liberation Army massing near a Shenzhen stadium. Since then, Beijing’s rhetoric has only grown more strident. China’s ambassador to the United Kingdom, one Liu Xiaoming, spoke of having enough power to ‘quell unrest’ if events become ‘uncontrollable’.

Such language sent a collective chill down the spine. After all, similarities abound. Both movements are student-led and both are asking for liberalisation from a famously illiberal government. We know how things ended in 1989, and we seem to be heading down the same bloody path.

2019 is not 1989. The protests at Tiananmen Square in the April-June of 1989 were an existential threat to the Chinese Communist Party’s rule over China. The Hongkong protests are not.

For starters, Tiananmen was on a much larger scale. In 1989, it wasn’t just Tiananmen Square which was crowded with student protesters; it was the whole of China. According to the Tiananmen Papers, there were protests, demonstrations and dissent in 341 cities across China. From Shanghai to Xian to Changsha, university students were thumbing their nose at the CCP by calling for suffrage and by forming independent student bodies—a massive taboo.

Hongkong’s protests are huge, but they’ve yet to reach 1989 levels due to a lack of support from the mainland. More importantly, however, the protesters of 2019 lack support from within the Chinese Communist Party itself.

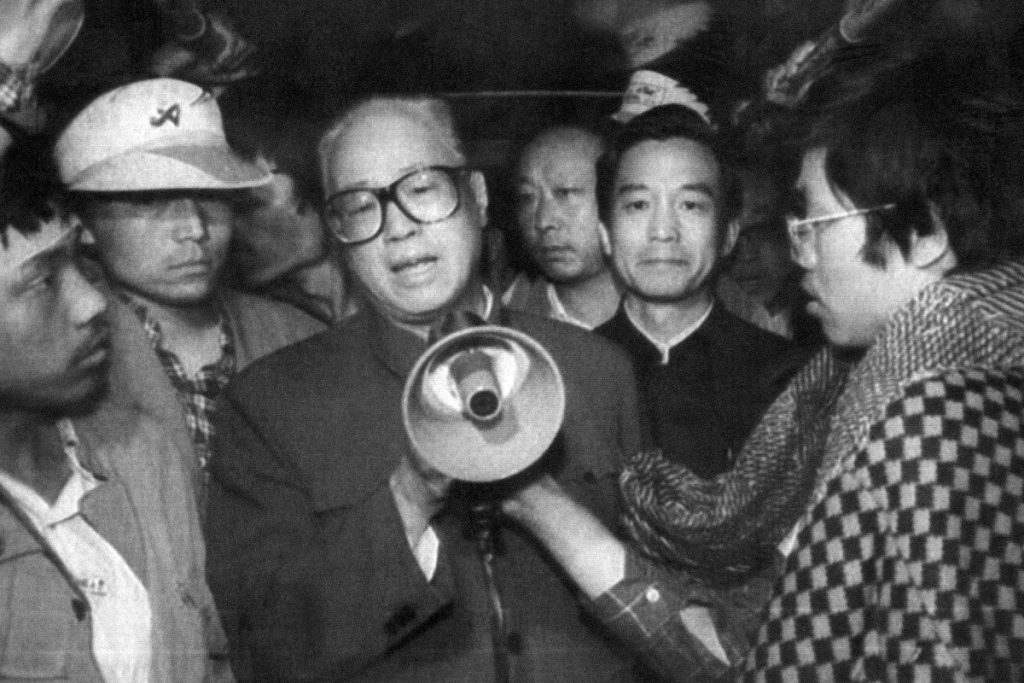

It is easy to forget this in Xi’s China, but the CCP is not a monolithic organisation which has always acted as one. In 1989, there was an influential faction of pro-reform party members who seemed in favour of western-style liberalisation. General Secretary Zhao Ziyang was the most famous of the reform clique, but it also included his predecessor Hu Yaobang and fellow Politburo members Hu Qili, Qiao Shi, and many others.

The real danger was this alignment between what the protesters were demanding and what many senior party leaders seemed to desire. Many hardliners were afraid that reformers would use the protests as an opportunity to further ‘open up’ China at the expense of CCP authority.

Hence, the party initiated a purge of the elites, followed by slaughter on the ground.

This all-important reform faction no longer exists. If Xi’s party still contained a liberal pro-reform wing, they’ve certainly kept a low profile. So low, in fact, that you could be forgiven for doubting its existence. As such, without support from above, Hongkong’s protests—however embarrassing—do not present an existential danger to the Party, and the Party is therefore unlikely to respond in kind.

Xi will not send in his tanks simply to save face.

Hong Kong’s protesters are fighting in the name of ‘democracy’, ‘suffrage’, and ‘human rights’. They are protesting in the name of ‘Western’ liberal values—values which have depreciated greatly since 1989.

Think back to the 90s. In those days, a self-confident United States (i.e. ‘The West’) believed that it was only a matter of time before the entire world became a liberal democracy open for business. Prof Francis Fukuyama’s 1992 The End Of History and The Last Man infamously predicted that liberal democracy would be the ‘final form of all human governments’ following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Countries which failed to live up to this ideal were frequently chastised and pressured to conform. Singapore—despite its pro-US stance during the Cold War—was rarely spared the rod. In those days, our ‘Ambassador-at-large’, Bilahari Kausikan, was frequently dispatched to criticize the critics.

Using a postcolonial slant, he argued against the western approach to human rights by invoking ‘cultural diversity’ and ‘Asian values’.

Who won those debates is irrelevant, but the very existence of a debate showed that liberal values possessed a certain amount of power. They presented a credible/captivating ideological alternative to authoritarian societies like Singapore and China, who were expected to become more open and more ‘free’ with the passing of time.

30 years later, Singapore is still the same. Liberalism, however, has fallen into a sort of disrepute. After Guantanamo, Brexit, The Patriot Act, Abu Ghraib, Netanyahu, Trump, two disastrous wars in the Middle East, and countless extrajudicial drone strikes in Pakistan, those cherished liberal values have lost much of their credibility and power. As such, they no longer pose an ideological threat to anyone, much less a resurgent Beijing.

After all, it’s hard to criticise your political opponents for their lack of press freedom and human rights, when your own president calls the press ‘fake news’ and sells weapons to aid Saudi war crimes in Yemen.

China has also grown stronger and wealthier in the meantime. These factors, when combined, insulate the CCP from both internal dissent and external pressure.

But don’t take my word for it, just look at the response to Hong Kong. Donald Trump has urged Xi Jinping to ‘speak’ with protesters while Boris Johnson has pledged to back Hong Kong ‘every step of the way’ whilst doing bugger all to back Hong Kong at any step.

Even by current standards, this is less substantial than the farts of a vegan ghost. It is like offering ‘thoughts and prayers’ after a mass shooting. No wonder Beijing is content to do absolutely nothing. Why would they, when the international backlash is negligible?

Take, for example, the Xinjiang internment camps. Over 1 million Uyghurs fenced up without trial is arguably much worse than either Tiananmen or the Hong Kong airport clashes. If the news had broke in 1994, there would be sanctions, boycotts and strong condemnations from all parties.

Bank accounts would be immediately frozen, at the very least.

In 2019, however, the news came and went like any other news story. Everyone just shrugged their shoulders and went: ‘Oh well, that’s China for you’. Faith in ‘democracy’ or ‘human rights’ has fallen so low that most nations no longer bother to even register their unhappiness, perhaps for fear of economic retaliation from Xi.

Once upon a time, it was theorised that economic liberalism will eventually bring about China’s political liberalization. Now, the opposite seems to be true: China’s economic liberalism has corrupted the West’s much-vaunted political liberalism. The CCP’s control is more complete than ever, because money and the indifference it buys is more potent than any PLA tank.