Simple and striking? Yes. Sensible and logical? No.

But it’s not worth devoting an entire article to debunking them. We need only quote Lawrence Sia, who was President of the Singapore Teachers’ Union from 1971 to 1982. In the late 70s, prompted by a debate raging in parliament about the status of Singlish (sounds familiar?), he led a team to England to talk to linguists. His reflection on that experience speaks for itself:

We went to England … and got in touch with the London University, a lecturer, an expert on English language. … And her point is that in England there is no Standard English, in fact, they are worse than us.

Anyone who has watched the video of a Scotsman puzzling over whether a kilogram of steel or a kilogram of feathers is heavier can understand why the lecturer said there is no such thing as Standard English even in its birthplace.

Why is it important to do so?

To quote Sia again: “A little interspersing of the local slangs does add flavour to the richness of the language”.

For instance, the first Singaporean poem to be written entirely in Singlish, Arthur Yap’s “2 mothers in a hdb playground” is loved by readers and academics alike, precisely because of its use of our vernacular. Robbie B.H. Goh, an English Literature professor at the National University of Singapore, describes the poem as capturing a “characteristically Singaporean … grammar and lexicon … [that] form the common currency of the Singapore people”.

In other words, Singlish, or any patois, for that matter, not only enriches our language, but also serves as a marker of identity. It endears the speaker to the local community, making them seem relatable.

Our politicians know of and constantly deploy this rhetorical strategy (to varying degrees of success): just think of kee chiu and si gui kia. According to Sia, even “Lee Hsien Loong and the Ministers use the dialect boh looi… [because as an] election tool [it’s] so effective”.

This is something Jason Leow, the Chairman of the Speak Good English Movement, is at pains to emphasise. He writes, “The use of Singlish outside formal and institutional situations is evident and widespread, and we acknowledge that it is a cultural marker for many Singaporeans … You don’t have to choose between standard English or Singlish. … If you can code-switch, more power to you.”

But wait … doesn’t the poster ask us to choose “the use of Standard English in everyday conversation”? Isn’t “everyday conversation” the furthest thing from “formal and institutional situations”?

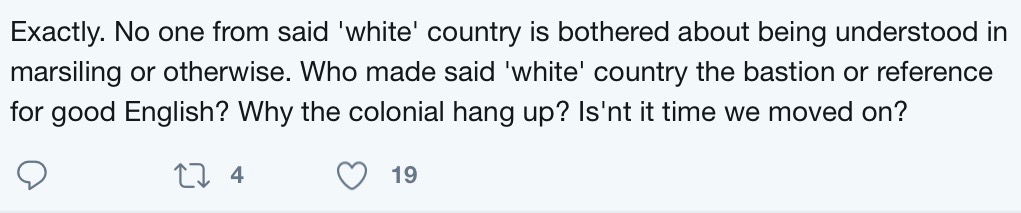

Moreover, isn’t it pretty hyperbolic (and close-minded and xenophobic) to argue that using Singlish or the Singaporean accent will make us unintelligible to a New Yorker? On the contrary, it is more likely that someone who grew up in a bubble of ‘Standard English’ and was unexposed to regional slangs and dialects will be lost in New York’s sea of tongues.

Along these lines, it seems contradictory to promote an authentic hawker culture on the one hand, and a sanitised language on the other. It’s rather like screaming to the world “char kway teow is an amazing Singaporean dish!” and instructing hawkers to describe it to foreigners as “rice noodles stir fried in soy sauce”. (Anecdote from my editor: “When I was on a flight back to Singapore I actually had flight attendants offer us ‘nasi lemak with curry chicken’ and ‘white rice with spicy chicken’ to ang mohs”.)

If the Speak Good English Movement truly wants to promote understanding and cultural immersion—in its call for Singaporeans to “connect with people across borders and cultures”—it should understand this: first, this relationship is two-way; second, there will be no culture left to connect with if everyone spoke in ‘Standard English’.