Inequality remains a pressing problem in Singapore. What can we do to narrow the gap?

Tell us what you think here.

With the lines that divide us becoming increasingly pronounced, we have to ask ourselves: is equality of opportunities a myth, or is it a reachable goal? Will the vulnerable or disadvantaged groups of society continue to lag further and further behind?

These are the issues that plague our society today, and youths are notably concerned.

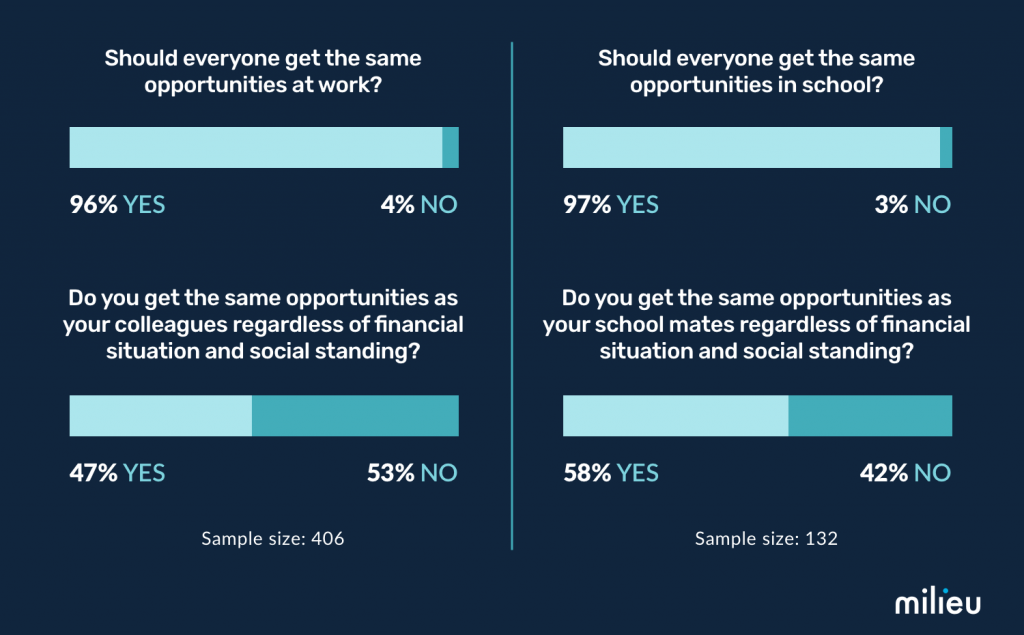

In a survey conducted by Milieu Insight, an independent research company, an overwhelming 96% of respondents believed that there should be equal opportunities in education and career for all.

But when asked if their personal experiences reflected this ideal, only half of the respondents believed that they were accorded the same opportunities in education and career in comparison to their peers.

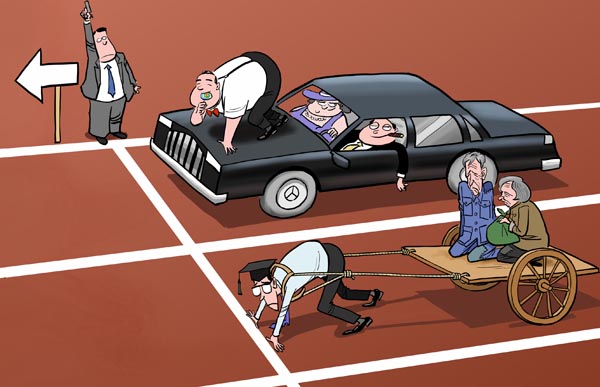

And what causes this chasm, according to a study conducted by the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, is the fact that factors like class, education, and ethnicity prevent the system of meritocracy from performing optimally.

The group of polytechnic students who were interviewed indicated that they do believe our national model of meritocracy can lead to upward socioeconomic mobility—at least in theory. But the aforementioned factors can have a compounding effect on disadvantaged groups, making it exceptionally difficult for them to achieve upward mobility.

If you’re Singaporean, I probably don’t need to spell this out for you. Having been sorted through the system, you have an innate understanding of how our system is clearly built to reward academic excellence and not much else. An ‘A’ on your report card is always going to be perceived as more valuable than displaying a keen eye for photography, or an aptitude in sports.

The fact remains that for lower-SES youths, what is considered the easiest or most surefire way to achieve upward mobility is through academic excellence. While this is achievable in theory, the reality is that not everyone has the same inclinations towards academics, or perhaps adequate resources or even a conducive enough environment to channel their energies into acquiring A-star grades. Compounded with our society’s narrow-minded definition of success, it makes it just that much more challenging for kids from lower income families to thrive.

While it is undoubtedly encouraging to recognise that young people are cognisant of these issues, what can we do about it?

Just last year, the release of Teo You Yenn’s wildly popular This Is What Inequality Looks Like, compounded by the viral CNA documentary on class divides precipitated uncomfortable but necessary conversations, bringing these issues to the forefront of our society’s consciousness.

So while there seems to be more dialogue surrounding the whole issue of inequality and how it’s been reproduced in our society, this is but the first step.

For instance, other than lower-income households, the respondents of the abovementioned Milieu survey identified individuals with physical and developmental disabilities to be among the members of society that require the most aid.

It has been estimated than only 5 out of 100 people with disabilities (PWDs) in Singapore are employed. At just around 5%, this rate is one of the lowest among developed nations.

As you might expect, the reflexive response of our youth is to turn to our leaders. More than two-thirds of young adult respondents reflected that they believe the government is not doing enough to ensure equal opportunities to disadvantaged communities.

“What is the gahmen doing (or rather, not doing)??” they might say.

Some respondents believe that while the government has been providing financial assistance to the needy and supporting vulnerable communities, perhaps more can be done. For example, the government can facilitate conversations with employers to encourage a shift in mindset regarding more inclusive hiring policies, or introduce more public policies to allow for better integration of vulnerable communities with the rest of society.

While it might not be immediately perceivable, it’s not completely fair to presume our government has been sitting around twiddling their thumbs. Some of their recent efforts have actually been directed towards addressing these very issues.

Recently, it was announced that the ComCare cash assistance schemes were revised to provide more financial aid to needy families. The Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth (MCCY) has also been making concerted strides towards promoting a strong arts, heritage and sports sectors—further proof that the government is not tone-deaf to the sentiments on the ground.

Additionally, with the specific aim of providing more support to the PWD community, Enable SG and The Enabling Village was specifically established. In various capacities, they work with commercial partners to provide employment opportunities to people “diverse in abilities, skills and ideas”.

Earlier this year, the Goh Chok Tong Enable Awards was also launched to acknowledge and celebrate the achievements of PWDs who have made significant contributions in their respective fields.

But while acknowledging this, we cannot solely rely on the faceless organisations to precipitate the reaction. Cliché as it is, we have to be the change that we want to see.

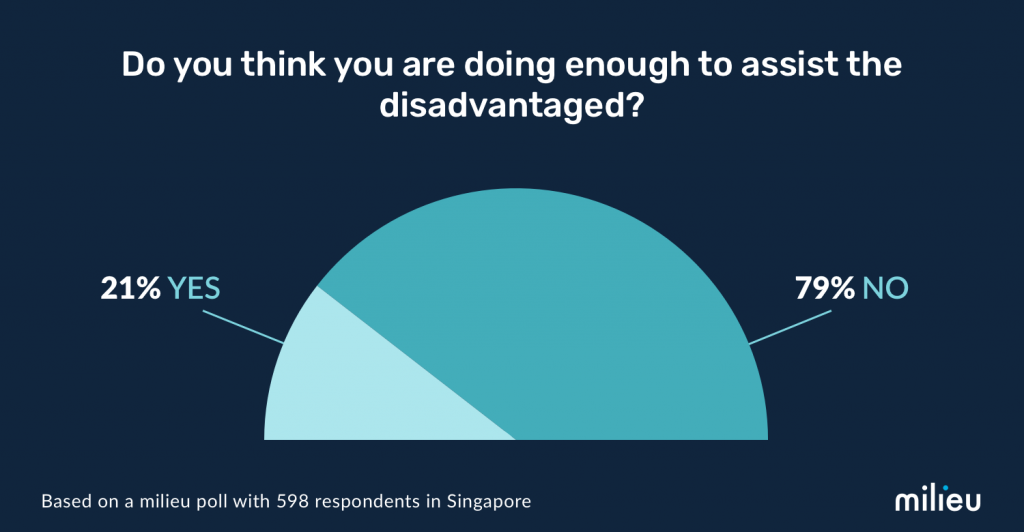

And our youth are starting to realise this. When asked whether they were personally doing enough to aid disadvantaged groups in Singapore, 21% of respondents responded in the affirmative. Though this percentage may seem paltry, I personally find it really encouraging.

Earlier this year, I had the opportunity to meet Jasmine Tan Xin Yi, founder of STARdy Kaki, a “youth-led group-up [initiative] committed to educational equality”. Based in Taman Jurong, they’ve provided academic related supplementary lessons, as well as organised excursion trips and value-based sessions for needy Primary School students over the past 3 years.

Through a personal acquaintance, I was also introduced to Superhero Me, a youth-initiated project funded by the Lien Foundation that aims to “realise and harness the creative potential of children with disabilities, special needs and from less-privileged backgrounds” through the medium of art. Since its birth in 2014, it has reached out to more than 18,000 people through a myriad of efforts: organising summer camps, conducting arts workshops, and even residency programmes for children with special needs.

Singaporean youths aren’t all whiny, apathetic millennials waiting for the tides to change. Slowly but surely, we are making small waves and ripples in whatever capacity we can. But of course, while it is important to highlight the labour and the triumphs of these youth, we also need to address the remaining 79%.

If we acknowledge the inherently human desire to prioritise self-preservation and self-gain, it’s easy to understand why people might not be able to justify expending energy to aid vulnerable groups, especially if their experiences don’t resonate with you.

But think about this disconnect another way: you obviously don’t want to be discriminated against for your gender, nor your race and religion, or your socio-economic class. You want a society that gives equal opportunity to all (including you).

Yet this isn’t possible unless you’re in a society that strives to uplift everyone—even the communities you don’t happen to identify with. So if we want to live in a more equitable society, the best way to achieve it is actively working to make it happen for others.

What can Singapore’s youth do to create a more equal society by 2025? Share your thoughts with NYC.

This article is part of the Visioning series by NYC, to hear what youths want for Singapore in 2025. Stay tuned for our next article in August where we’ll be sharing your responses on how we can build a better Singapore.